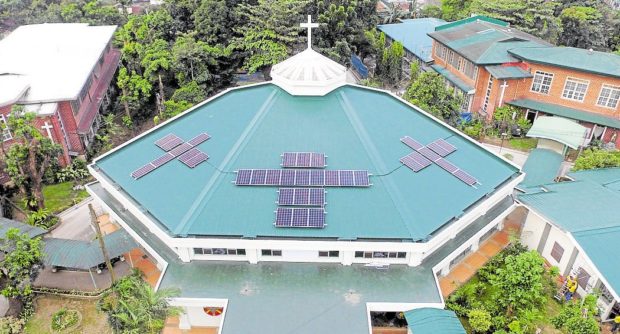

CLEAN FUEL FOR THE FAITHFUL Solar panels form three crosses on the rooftop of the Chapel of the Religious of the Good Shepherd in Quezon City. —PHOTOS COURTESY BY WEGEN LAUDATO SI

MANILA, Philippines — In the past few years, Bishop Gerardo Alminaza of the Diocese of San Carlos in Negros Occidental has been at the frontline of a crusade waged both from the pulpit and on the streets.

Alminaza, 61, is part of the Philippine Catholic Church’s strong opposition to the use of fossil fuels in the country. And the threat to the diocese looms large: a proposed 300-megawatt coal-fired power plant in its coastal city.

But the bishop understands that beyond dialogues and campaigns, the Church can and should be doing more to demonstrate its seriousness in rejecting fossil fuels. “We cannot just oppose and oppose,” he says. “We have to be more proactive.”

Happily, their avowed intention shows.

In 2017, San Carlos became one of the first dioceses in the country to formally sign a partnership with an energy resource company to install solar panels on the roofs of three of its buildings, including the seat of the diocese, the San Carlos Borromeo Cathedral.

That they are blessed with sunshine is an understatement. Negros Island, already dubbed the renewable energy capital of the Philippines, has solar power comprising nearly half of its installed capacity mix, according to a 2020 scoping study by the think tank Center for Energy, Ecology and Development (CEED).

Nationwide, more dioceses are pivoting toward solar energy to power up parish churches, schools and seminaries — both a manifestation of the Church’s commitment to a just transition to renewable energy sources, and a showcase of its call to the government to rethink energy policy amid the climate crisis that threatens the most vulnerable in its flock.

Care for common home

The Catholic Church in the Philippines, with 85 dioceses, is by no means an energy-intensive sector. But its vigorous campaign for the faithful to withdraw support from fossil fuels is seen as a potential inflection point in a country that continues to depend heavily on burning coal for power and energy needs.

The Philippines is home to the biggest Catholic population in Asia and the third largest in the world. Among 110 million Filipinos, at least 8 of 10 are Catholic, making of the Church a moral and political force.

The Church’s involvement in social justice and environmental issues is not new. Catholic priests and nuns have long taken their preaching to the streets, standing with communities against destructive activities such as illegal logging and large-scale mining.

These advocacies took a new dimension in 2015, when Pope Francis issued the “Laudato si,” his second encyclical that called for the “care for our common home.”

“There is a traditional belief that the Church should not meddle in social and environmental issues, that it only needs to focus on its role of giving the sacraments and celebrating the liturgies,” notes Fr. Edwin Gariguez, the former executive secretary of the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines’ National Secretariat for Social Action (CBCP-Nassa), the humanitarian and advocacy arm of the Church.

Gariguez adds: “But Pope Francis himself has said that we have a responsibility for social transformation, part of which is our obligation for the environment and to help the poor. And the ‘Laudato si’ is a mandate, an imperative from the Church.”

In his 180-page encyclical, the Pope lamented the destruction of the environment, explicitly mentioning fossil fuels as the factor behind the rapidly warming planet. “We know that technology based on the use of highly polluting fossil fuels—especially coal, but also oil and, to a lesser degree, gas—needs to be progressively replaced without delay,” he wrote.

Gariguez says this has been the big push for the global Catholic movement, including in the Philippines, to streamline its activities from education drives to signature petitions in an effort to bring awareness and pressure to governments to shift away from coal.

SHIFT TO RENEWABLES Catholic dioceses across the country are making a shift to solar energy to power up their buildings, from parishes to seminaries, convents and schools, such as St. Joseph College in Maasin City, Leyte province.

Mainstreaming the shift

While some Philippine parishes had individually moved to “solarize” and green their churches, Pope Francis’ clarion call prompted the Church’s national leadership to mainstream the shift toward clean and renewable energy.

In October 2016, the CBCP’s Episcopal Commission on the Lay Apostolate, with its implementing arm Sangguniang Laiko ng Pilipinas, entered a partnership with WeGen Laudato Si Inc., a special-purpose company formed by WeGen Distributed Energy taking inspiration from the Pope to work closely with faith groups in the country.

A distributed energy resource company, WeGen operates in the Philippines and in Vietnam, focusing on renewable energy technologies, particularly solar energy.

Aside from the goal shared by the Church and the company, what speeded up this partnership was a bridge: Jun Cruz, the director of relations of WeGen Laudato Si and a member of Laiko.

Facilitated by Cruz, a memorandum of agreement was signed to assist Catholic dioceses interested in using solar power for their buildings. Each diocese being autonomous and self-reliant, WeGen Laudato Si spoke with individual bishops to pitch the benefits of harnessing the sun’s energy for their power needs.

Their efforts in the last five years appear successful. WeGen Laudato Si has sealed partnerships with 74 of the 85 dioceses. Solar panels have been installed in nearly 200 religious or Church-owned buildings in at least 45 dioceses from the Prelature of Batanes in the north to the war-torn Prelature of Marawi down south.

World’s first

The biggest project so far is in the Diocese of Maasin on Leyte Island which, in 2018, became the first diocese in the world to completely shift to solar energy use.

The Vatican commended the diocese for this effort during the 5th anniversary of “Laudato si” last year.

The installed solar panels in 42 parishes and a school building has a system size of 234 kilowatt peak (kWp). Bishop Precioso Cantillas has said that shifting to solar allowed them to save at least P100,000 a month in power bills—resources that the Church can funnel into its other socio-civic activities.

At the Diocese of San Carlos, Alminaza says they have yet to fully calculate their savings from the installed 12-kWp system in their buildings. As in other dioceses, their system does not have battery storage and is still tied to the grid. This means that during the day, the solar panels power up their buildings, but their energy consumption is hooked back to the existing power grid once the sun sets.

The technology for battery storage remains expensive, pushing dioceses to forgo this option.

WeGen Laudato Si’s solar panels on rooftops may pale in comparison to huge solar farms that generate megawatts of electricity, but this is exactly how they envisioned their work to be, says Cruz.

“Our projects are small compared to other companies,” he says. “But even if it’s a small parish on an island that only requires 3 kWp, we install our panels because our vision is really clean and affordable energy, anytime, everywhere, for everyone.”

Other players

Other companies tried to strike similar deals with the Church to provide solar panels to dioceses, Gariguez recalls. None has prospered, he notes, perhaps given the challenges of dealing with individual prelates in dioceses that are smaller, far-flung, and with less resources.

“For a company that is profit-driven, the Church may not be as appealing” to do business with, Gariguez says. “But if there will be other players who can offer cheaper prices, then it will encourage competition, and it’s the parishes that stand to gain.”

With WeGen Laudato Si, Church leaders are presented cost-benefit analyses and financial studies based on the diocese’s power needs and capacity to pay, says Cruz.

Most, if not all, of their projects offer no cash-out and have payment terms that can extend to 15 years.

Such a setup does not allow for a quick return of investment, with the company spending at least P70,000 per installed kilowatt peak, Cruz says.

“From the start, we [tell] them that we are a business and not a nongovernmental organization,” he says. “Solar panel systems may still be expensive, but they are definitely cheaper now… With the panels installed, we explain to the Church leaders that whatever they can save from their electricity bills, instead of paying it to a distribution company, they can use it to pay us.”

SHINING ON THE FLOCK Encouraged by Pope Francis’ encyclical “Laudato si,’” the Catholic Church in the Philippines has been pivoting to solar energy one parish at a time. In Malabon City, San Bartolome Parish Church has installed solar panels on its rooftop.

Hit by pandemic

But even with the options offered by the energy firm, many dioceses are still reeling from the financial hit of the COVID-19 pandemic. The lockdowns require the faithful to stay home, resulting in massive reductions in Mass collections that are the primary source of funding for the parishes.

“I think there is no longer an argument on the shift to renewable energy for the protection of the environment,” says Fr. Antonio Labiao, the current executive secretary of CBCP-Nassa. “I think what our priests and lay leaders are more concerned with is the cost.”

“Many of our dioceses now, especially in the provinces, are struggling to survive. So pushing for the implementation of solar energy might take some time,” he says.

But the pandemic may just lead the country to pursue a cleaner energy pathway, environment experts and advocates say.

“The pandemic is an opportunity for green recovery, a just recovery,” says lawyer Avril de Torres, head of the CEED’s research, policy and law program. “This must focus on reformulating energy plans, so we don’t go back to the ways of the past and we move forward by being powered by renewable energy.”

Department of Energy data show that the Philippines is still heavily reliant on fossil fuels, particularly coal and oil, for its energy needs. There are 28 coal-fired power plants nationwide, with an existing capacity of 9.88 gigawatts. At least 19 other coal plants remain in the pipeline, putting the Philippines among the top countries in coal expansion.

Renewable energy advocates are hopeful that the pandemic will give wind to the shift to sustainable energy, especially with consumers burdened with high electricity bills and communities with coal plants clamoring for urgent change, says De Torres.

“There are a lot of renewable energy mechanisms that will become effective, that we are hopeful for… but unless there is a clear phaseout policy, renewable energy cannot displace coal,” she says.

Symbolic to concrete

As Filipinos face more supertyphoons and intense droughts each year, the Catholic movement toward cleaner energy further crosses from symbolic deeds to concrete actions.

Beyond their shift to solar power, Catholic dioceses and other faith groups have moved forward to demand that banks and other financial institutions withdraw their investments from coal and fossil fuel industries. A number of bigger dioceses and religious groups sit as top shareholders in these institutions.

“We are happy that there are so many Catholic dioceses that are already putting up solar panels, but it should not stop there,” says Rodne Galicha, executive director of the interfaith movement Living Laudato Si Philippines. “You cannot just put solar panels and not [urge] companies and parishioners to not patronize services and products that are harmful to the environment.”

In Catholic-majority Philippines, the groundwork is set, says Galicha, with the Church possessing the machinery and architecture to influence the conversation on energy democracy and environment protection.

But for actual changes to take effect, the collective action of the faithful, not just the chosen few, is needed—and this is not expected to be done overnight.

As he envisions a more sustainable energy path for his diocese and the entire Negros Island, Alminaza believes that Church leaders like him can truly make a difference and rally their flock behind a good cause: the survival of the planet, of which humans are the stewards.

“The challenge I see is for the Catholic population to wake up,” he says. “Ecological conversion takes a while… and even with consecutive calamities, people don’t see yet the connection [of our actions to the planet].”

“But we cannot say we love God,” he says, “and then neglect and keep destroying the environment.” INQ

—

This report was written and produced as part of a media skills development program delivered by Thomson Reuters Foundation. The content is the sole responsibility of the author and the publisher.–Ed.