Coronavirus pandemic shrinks Europe’s monitoring of US polls

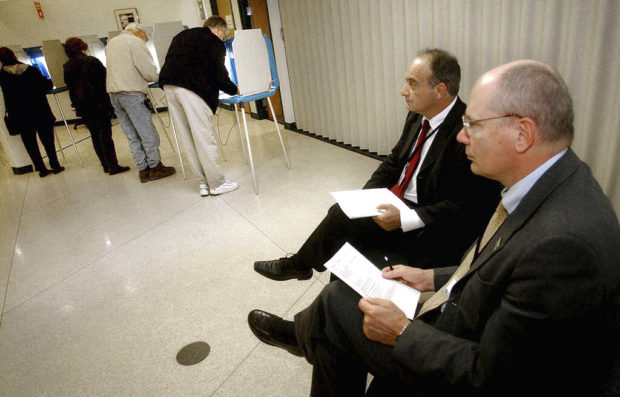

FILE – In this Nov. 2, 2004, file photo, parliamentarians Goran Lennmarker, right, of Sweden and Stavros Evagorow, of Cyprus, observe the American voting process as voters cast their ballots at Robbinsdale City Hall in Robbinsdale, Minn. The two men are members of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe. Officials said Friday, Sept. 18, 2020, that due to the coronavirus pandemic, the security organization had drastically scaled back plans to send up to 500 observers to the U.S. to monitor the Nov. 3 presidential election, and now will deploy just 30. (AP Photo/Jim Mone, File)

Washington — Europe’s largest security organization said Friday that it has drastically scaled back plans to send as many as 500 observers to the United States to monitor the Nov. 3 presidential election and now will deploy just 30 because of the coronavirus pandemic.

The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe — which has observed U.S. elections since 2002 but is better known for monitoring voting in countries such as Belarus or Kyrgyzstan — has spent months trying to figure out how to safely keep tabs on an election it worries will be “the most challenging in recent decades” as Americans pick a president in the throes of a global health crisis.

The use of mail-in voting is expected to increase in many states this year, with voters seeing that as a safer alternative to casting ballots in-person during the pandemic. Although President Donald Trump has claimed that an increase in mail ballots could lead to a rigged election, there has been no evidence of widespread fraud involving voting by mail in the U.S.

The OSCE’s mission originally was to have involved 100 long-term and 400 short-term observers to the U.S. starting this month, but health concerns and restrictions on travel prompted the Vienna-based organization to pare that back to 30 observers, spokesperson Katya Andrusz told The Associated Press.

Suddenly, what was going to be Europe’s largest-scale U.S. election monitoring effort ever has become one of its smallest. The OSCE sent 49 observers for the 2018 midterms and about 400 for the 2016 presidential election.

Article continues after this advertisement“While we had planned to send a full-fledged election observation mission, the safety fears as well as continuing travel restrictions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic are creating challenges,” Andrusz said in an email. The 30 are expected to head to the U.S. early next month and will stay through Nov. 3, she said, adding that none of the observers is from Russia.

Article continues after this advertisementLast March, the U.S. mission to the OSCE had requested observers, as all countries belonging to the group, including Russia, are obligated to do. The organization’s Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights has deployed monitors for U.S. voting since the 2002 midterm elections — the first since the 2000 presidential election recount that left the outcome unclear for weeks, raising questions among America’s allies about the integrity of its electoral politics.

Typically, the organization sends a small delegation months before an election to do a “needs assessment,” but that was conducted remotely in early June “due to the global health emergency and restrictions on cross-border travel,” officials said.

The European security group also has publicly criticized the Electoral College system in the U.S., saying it “does not provide for equality of vote” like a popular vote would do.

Even if observers were granted access, many U.S. states don’t allow them, and others leave it to the discretion of local elections officials. Only California, Missouri, New Mexico and Washington, D.C., expressly allow international monitors.

Calls have been mounting for extra scrutiny of November’s election — and not just with domestic observers, as the Carter Center intends to do.

“The United States touts itself as the democratic model that nations around the world should emulate. But if America really wants to be the exemplar of democracy, then it should prove its elections are, in fact, free and fair, and let the world watch,” The Boston Globe said in an editorial last month.

In a July report expressing concern about the U.S. vote, the OSCE said the 400 short-term observers would include some who would be focused solely on media coverage in the days and hours leading up to the vote. It was unclear Friday whether the trimmed-down “limited observation mission” would include a media monitoring element.

“In an atmosphere of increased polarization, and accusations from all political sides on potential voter fraud and mistrust in the election process and results, the presence of external observers to assess the process will be highly valuable, adding an important layer of transparency,” it said.

Timothy Rich, a professor of political science at Western Kentucky University, contends that “ensuring fair elections is an essential component of American democracy.”

“International monitors have shown they can provide an effective means to reduce public concerns about fraud and voter suppression,” Rich wrote in a recent commentary for The Conversation.