Group sets off alarm over forest turtle trade

A wildlife trade monitoring network has sounded the alarm on the massive illicit trading of the Philippine forest turtle (Siebenrockiella leytensis), previously thought to be extinct until rediscovered by scientists in Palawan forests 19 years ago.

The illegal trade of the critically endangered species is comparable to “puppy mills,” where breeders hide behind legal loopholes and illegal documents to carry out local and international commercial sale.

The Philippine forest turtle is among the top 25 “most endangered” turtle species in the world, with known populations in the wild traced to Dumaran Island and northern Palawan, according to the London-based wildlife trade watchdog, TRAFFIC.

The turtle species appeals mostly to hobbyists, while there is no evidence yet to show it is being traded for food, the group said.

Exit point

TRAFFIC on Thursday disclosed a possible smuggling route of the turtles from the Philippines’ “exit point” in Taytay town, Palawan, to Europe, before the turtles were reexported undetected to other countries. This was based on the “seizure analysis” of Philippine forest turtles from 2004 to 2018, which documented 23 instances when authorities seized turtles from smugglers. It was published in the Philippine Journal of Systematic Biology on Aug. 11.

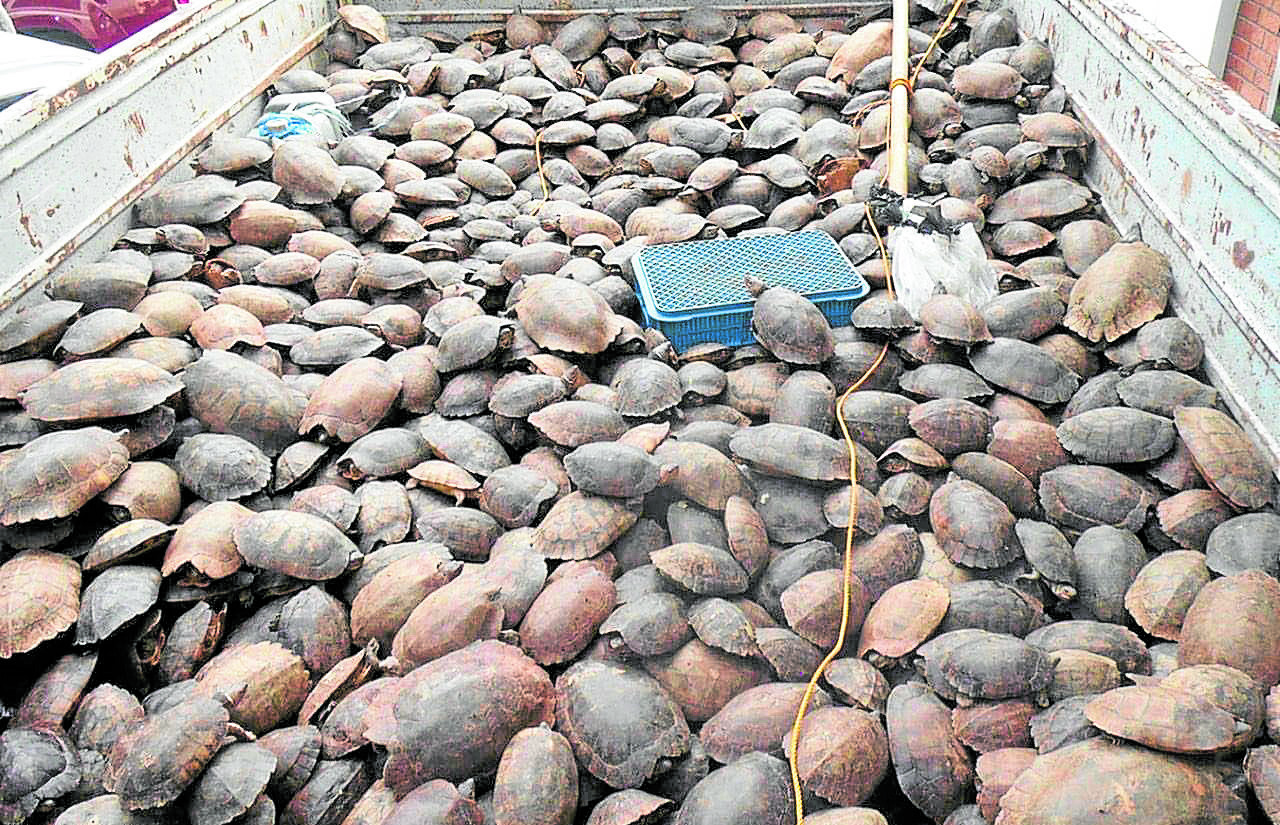

According to the research, 4,723 turtles were seized during that period, the majority of which were from Palawan.

Article continues after this advertisementEmerson Sy, a herpetologist and TRAFFIC’s lead author, said that as a “conservative estimate,” about 2,500 more Philippine forest turtles could have been illegally sold but not recovered over the last 15 years.

Article continues after this advertisement

PALAWAN HAUL In this 2015 photo, a large haul of Philippine forest turtles about to be shipped out of the country is seized in Bataraza, Palawan. A wildlife monitoring group says 4,723 Philippine forest turtles have been recovered from traders from 2004 to 2018. —PHOTO COURTESY OF EMERSON SY/TRAFFIC

Legal cover

The year 2004 marked a significant turn of events when science journals published the rediscovery of Philippine forest turtles, the species unheard of “for the longest time” until 2001, Sy said.

He believed it alerted poachers to the breeding grounds and triggered the trafficking.

“As early as 2004, there was already a market [for Philippine forest turtles] in the United States, Japan, Europe and over the years in China,” Sy said in a telephone interview.

The Palawan Council for Sustainable Development has not issued any permit to transport, sell, or breed the Philippine forest turtle since 2004. But the implementation in 2004 of Republic Act No. 9147, or the Wildlife Resources Conservation and Protection Act, has allowed the mass “registration” of all wildlife species in the custody of private collectors or facilities, like zoos and farms, including illegally acquired Philippine forest turtles.

Sy said it was some sort of an “amnesty, [but which also] provided the legal cover” for the “laundering” of the endangered species.

Captive breeding

He said the latest government data placed the Philippine forest turtle population at 3,000 from 2013 to 2014. But he doubted this figure after the seizure of 3,921 turtles in Palawan in 2015, the single biggest operation so far.

Technically, breeding the turtles in captivity and selling its offspring is legal as long as breeders presented documents for the “parental stock.”

Online, an adult Philippine forest turtle, which can grow to a foot long, fetches P15,500 in the Philippines and about $4,500 each in the international market.

“There was one farm in (Calabarzon region) that claims to have hatched 50 [turtle eggs] at the same time in 2016. That just does not happen,” Sy said.

According to him, the Philippine forest turtle is one of the “most difficult to breed” species, considering its longer incubation period, that the only documented and successful captive breeding was done by the nongovernment Katala Foundation.

Katala produced only nine turtles since 2018, after 12 years of breeding, he said.

According to Sy, the Philippine forest turtle is a predator that controls the population of other species, like shrimps and snails. Its presence in the wild, he said, also helps in seed dispersal to preserve ecological balance.