Lantern makers keep tradition aglow

July marks the start of the season of making lanterns in the City of San Fernando, touted as the Christmas capital of the Philippines.

But midway to August, Arvin Quiwa’s workshop at Purok 10 in Barangay Sta. Lucia was still almost empty. Some supplies were stacked at a corner of the two-story building. No workers welding frames or fitting sequencers. No Christmas songs playing in the background.

It was in stark contrast to the scene last year when the 46-year-old Quiwa would have already spent P10 million on labor, supplies and marketing.

“In July 2019, I got 22 contracts [for making street lanterns]. It was only last Monday that I clinched my first deal [from the local government of Angeles City],” said Quiwa, who started designing home and giant lanterns at age 13 and ventured on his own at 26, with Olongapo City as his first client.

Clark Freeport in Pampanga, Subic Bay Freeport in Zambales, and Marikina City have called for designs and costs. There are no inquiries from abroad.

To Quiwa, the cancellation or delay of orders and expected low sales are effects of the new coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic.

Article continues after this advertisementIn a clan that makes lanterns both as a religious tradition and commercial venture, this fifth generation craftsman saw COVID-19 as threatening to seize the joyful spirit of Christmas.

Article continues after this advertisement

PAMPANGA STAR Each giant Christmas lantern showcased in the City of San Fernando’s “Ligligan Parul” (Giant Lantern Festival) every December is a product of teamwork and collaboration of craftsmen and community members. The “parul” represents the biblical Star of Bethlehem that guided the Three Wise Men to the manger where Christ was born. —PHOTOS BY TONETTE OREJAS

Christmas mood

But Quiwa is confident that Filipinos will not let the gloom of COVID-19 darken the Christmas mood.

“When the ‘ber’ months come, we become excited about Christmas and no matter what, we will celebrate the birth of Christ. Our lanterns, especially the giant ones, are like stars on that holy night,” he said, explaining the Christian undertones of their creations.

Since contracts are starting to come, he has called back to work 20 of his 100 workers, who also drive pedicabs or tricycles for a living.

Quiwa’s optimism is inspired by his father, Ernesto, who, at 73, is the oldest lantern maker in San Fernando.

Ernesto made four of the seven lanterns that were featured in the giant lantern festival at Paskuhan Village in December 1991, or just six months after Mt. Pinatubo’s eruption.

“We are sad. But must we be sadder?” Ernesto then said.

This great-grandson of Francisco Estanislao, the acknowledged pioneer in the field, made one that had two doors in the center, which opened to reveal an erupting volcano. He remembered that the audience clapped so loudly at the sight.

“The Christmas spirit must prevail in times of disasters,” Ernesto said.

To Roland Quiambao, 64, COVID-19 is a totally different problem. “Firstly, it is happening worldwide. Secondly, you cannot move around to learn new designs or look for supplies,” he said.

The idle scene in Quiwa’s workshop is similar to that in the two wide compounds of Quiambao in Barangay Del Pilar, also in San Fernando.

FAMILY ENTERPRISE Ernesto Quiwa, 73, (top) has spent 60 years of his life making “parul,” the Christmas lanterns in various sizes adorning homes and establishments during the holidays. His son, Arvin, 46, has followed in his footsteps, with his creations reaching exhibits and clients abroad.

Pitiful situation

To help his 40 workers earn when the quarantine eased in May, Quiambao made them build a stock of 1,000 “capiz” lanterns to sell in the “ber” months.

They also tried their hands in building computer tables. In between, they grew vegetables on Quiambao’s 1,500-square-meter lot.

“It was a pitiful situation. Nobody lent us money so I decided to use my savings to help us tide through the lockdown. Some have taken jobs in construction projects,” he said.

By this time, he would have spent P4 million on labor, materials and marketing.

He had been tapped to make street decors for San Pablo City in Laguna province, San Carlos City in Pangasinan province, and San Juan City in Metro Manila, enabling him to take back 10 workers.

Quiwa’s siblings, Eric and Che-che, have taken to online selling, filling local and overseas orders.

Eric, who is usually tapped by government agencies to produce lanterns for national events, had used up his savings when he shifted to making commercial fiberglass lanterns to sustain eight of his 40 workers.

“The lanterns are not perishable items so it is OK if these are not sold at once. But I think I will sell because I put a nativity scene on stained glass,” Eric said. He also designed a lamp as a droplight for which he got an order for 100 pieces.

Orders for lanterns covered with capiz shells still come from Canada and the United States, Quiambao said.

The 26 small businesses that are registered as manufacturers and sellers of lanterns are also gasping for life, data from the investment promotion division of the city government showed.

These have been endorsed for loans from the Department of Trade and Industry. In September, they are scheduled to receive P20,000 worth of raw materials. The Giant Lantern Festival Foundation gave P20,000 to lantern-making teams.

“We are all struggling to survive,” Quiambao said. “But [no one] is giving up.”

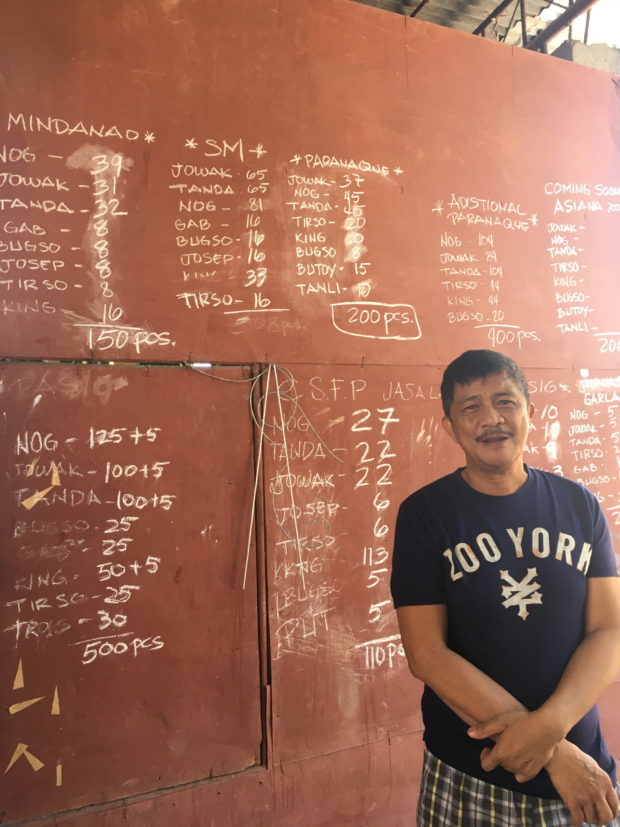

RECORD-KEEPING Roland Quiambao, one of the highly regarded lantern makers of Pampanga, records the output and payroll of his workers on a wall in his workshop in the City of San Fernando.

‘Ligligan Parul’

The 112th Ligligan Parul (Giant Lantern Festival) in December appeared to be headed for a scaled-down version. “People will feel hopeless without the festival,” Quiambao said.

Safety protocols are big considerations in the planning, according to Ching Pangilinan, San Fernando tourism officer. Past festivals drew as many as 50,000 people.

Ernesto suggested doing away with the competition so less expenses are incurred. “The lanterns should be operated to perform and make people happy,” he said. “We need to lift the Christmas spirit.”

Lanterns that stand as high as three-story buildings are made in November. The set of rotors, the contraption that turns the lights on and off, is redone to follow new lighting patterns.

Immediately after the festival, all lanterns are brought to the Metropolitan Cathedral at the city proper to draw people to the Christmas Eve Mass.

It used to be that rotor operators made the lanterns perform beside the village’s patron saint but this practice had been stopped in the 1990s.

“In whatever way the festival will be done now, the important thing is that our lanterns will light like the stars of Bethlehem,” Quiambao said, referring to a Bible story about the birth of Christ in a lowly manger more than 2,000 years ago.

For more news about the novel coronavirus click here.

What you need to know about Coronavirus.

For more information on COVID-19, call the DOH Hotline: (02) 86517800 local 1149/1150.

The Inquirer Foundation supports our healthcare frontliners and is still accepting cash donations to be deposited at Banco de Oro (BDO) current account #007960018860 or donate through PayMaya using this link.