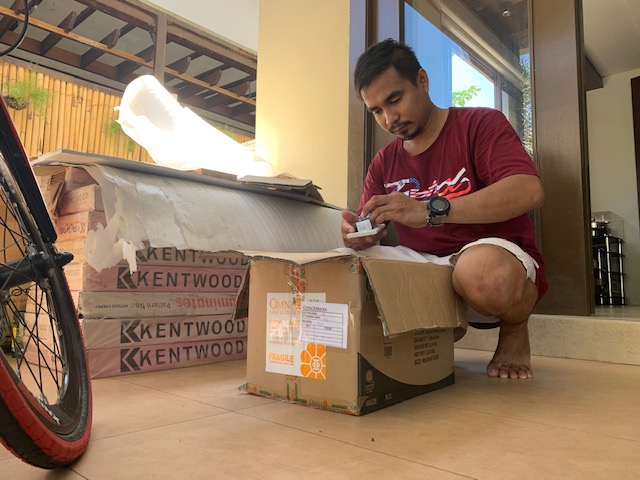

READY FOR WORK Carpenter Raymart Orosa examines hardware he was supposed to use at a home in Parañaque City before the lockdown. —CATHY CAÑARES YAMSUAN

MANILA, Philippines — Ronald Orosa, a 35-year-old “habal-habal” driver, has already received three traffic citation tickets for illegally transporting passengers on his motorcycle since Luzon was placed under enhanced community quarantine (ECQ) in March.

As it is, ride-sharing is not allowed under the ECQ. In Orosa’s case, habal-habal means he has not even acquired the proper accreditation from transport authorities for his vehicle to accommodate passengers at all.

Barely enough

“Even the police officers who accost me know how difficult my situation is. They tell me to stop taking passengers but I still do it because I have no job. And the ECQ only made things worse,” Orosa said as he dabbed his eyes with a handkerchief.

Orosa lives in a rented room the size of three washroom cubicles with his common-law wife and a 3-year-old daughter.

He leaves at 3 a.m., supposedly when the cops are already tired of patrolling the stretch of Sucat Road in Parańaque City near the South Luzon Expressway.

His self-imposed 20-hour shift that ends at 11 p.m. nets him P500 on a lucky day, barely enough to pay for food, drinking water, electricity, rent and daughter Yhumi’s diapers.

More than the dreaded COVID-19 disease that has forced the government to impose the ECQ, Orosa said he is more worried about the current weather that brings intense heat during the day and rain shower in the early evening.

“But we carry on,” Orosa tells himself whenever he searches for passengers. “Some days I would already be tired and sweaty and a sudden rain would leave me drenched. But it’s either this or my family dies of hunger.”

Financial loss

Before the lockdown, Orosa’s younger brother Raymart would ask his “kuya” (older brother) to join him on carpentry jobs in affluent communities in southern Metro Manila.

Raymart, who just turned 30, had four pending house repair projects when President Rodrigo Duterte initially imposed a Metro Manila-wide community quarantine that promptly became Luzon-wide until this was enforced throughout the country.

This meant Raymart and his team were barred from entering gated subdivisions where their clients live.

He calculated his financial loss at about P20,000 a month since March 16, the start of the lockdown. Raymart is now stuck in a 4 x 3 square meter rented room that he shares with his common-law wife, a 4-year-old daughter and two adult relatives.

Raymart at least made the cut when barangay officials chose 40 male volunteers to man the community gate that leads to their neighborhood of informal settlers in Barangay BF Homes.

“The volunteers get rice donations. Sometimes it’s two kilos per person, sometimes four. The supply is not steady but since I don’t have a job, I cannot complain. I still receive something for guarding the gate between 10 p.m. [and] midnight,” he said.

Assistance

The Orosa brothers live in the same community. Since the ECQ began, they have received assistance from the Parañaque city government three times, ranging from vegetables to relief goods that included rice and canned sardines.

“It’s never enough for the people at home,” Raymart said. “Four adults and a child require 1.5 kilos of rice already. But we still consider ourselves lucky. In another rented room near us are five men who are all unemployed because of this lockdown. There are times when I give them the rice I get for guarding the gate.”

Still, the brothers are grateful that despite the recent alarm raised by the city government over rising cases of COVID-19 in their area, their street remains free of the new coronavirus that causes this disease.

“Everyone knows not to leave their homes unnecessarily. The only issue is the heat. When it becomes unbearable, my daughter and I just step out the door to get some air. We don’t go anywhere. Not even to the gate,” Raymart said.

Bright side

“We are scared of the virus. It is something we cannot see. We still watch TV. We realize it’s better to have an enemy we can see, at least we know which area to avoid. Unlike this virus.”

Raymart remains optimistic he will resume his projects to some degree when Metro Manila shifts to a general community quarantine by Monday.

By then, restrictions on mobility would be more relaxed, he assumes.

Ronald Orosa hopes that driving a habal-habal would eventually get him to save enough to start a “carinderia.”

“I used to be a cook so I know how to do a lot of Filipino dishes. Such skills are not easy to forget,” he said.

The brothers still manage to look at the bright side of the quarantine.

“One lesson I learned is to stay healthy whether or not there is a pandemic. To take care of one’s self and keep clean even if there is no more lockdown,” the older Orosa said.

A valuable realization for Raymart is saving cash (“pagtitipid”).

“It’s so hard to rely on ‘ayuda (help),’” he said.