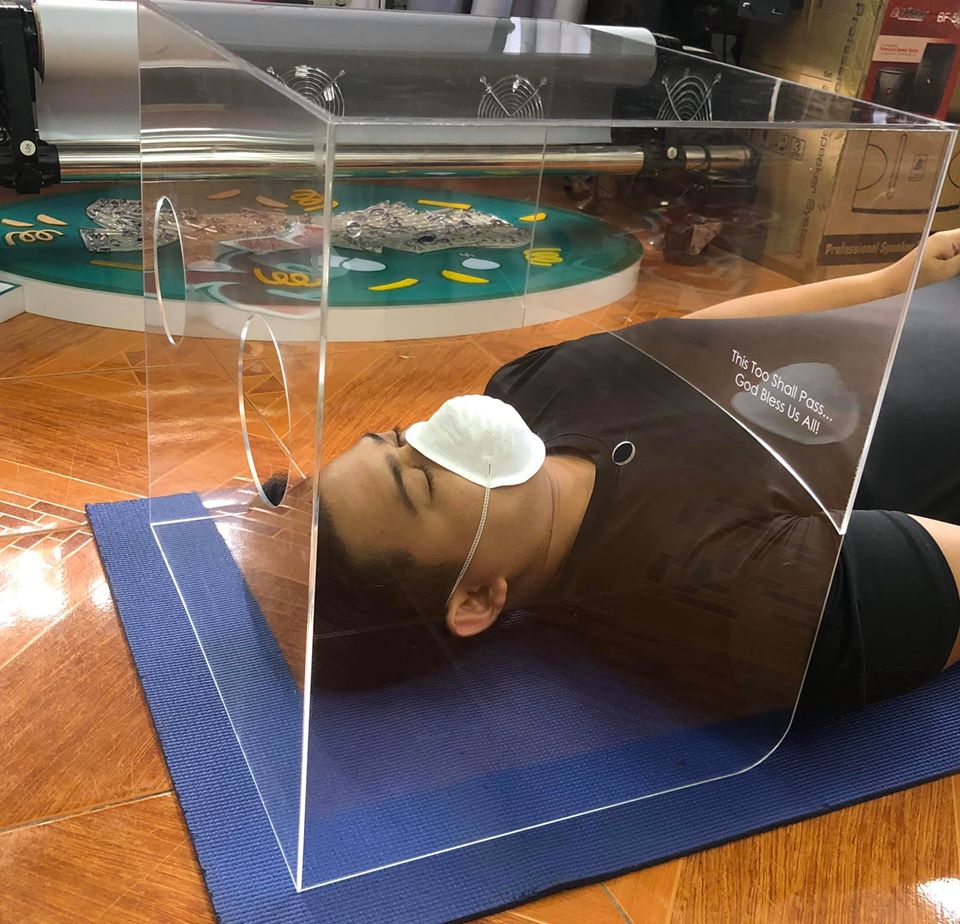

John Rhen Luzon’s prototype of the aerosol box which will be used by doctors in intubating COVID-19 patients. Image: Facebook/Jao Achie

It all started with one doctor’s call for help.

John Rhen Luzon, owner of local fabrication company Team Flash Enterprise and Advertising Co., stumbled upon a Facebook post by Neyziel Mardo, a doctor at the Rizal Medical Center, a week into the enhanced community quarantine on March 22.

Dr. Mardo’s post offered a glimpse into how doctors in her hospital use plastic drapes as protection when intubating COVID-19 patients. She asked the public for help to acquire aerosol boxes, which can also protect doctors and nurses from infection during the intubation process.

Luzon did not waste any time after seeing the good doctor’s post. He immediately sent a message to her for specifications of the aerosol box and got to work. By the next day, he had already finished a prototype, ready to be sent to Dr. Mardo’s hospital for testing.

At that point, it was no longer a matter of business, but of civic duty.

“Since the beginning, the initiative has always been to help. The actual thought is the help, the reaching out, that we give to those in need of it,” Luzon told Inquirer.net.

John Rhen Luzon’s prototype of the aerosol box which will be used by doctors in intubating COVID-19 patients. Image: Facebook/Jao Achie

PPE shortage

As of April 22, a total of 1062 health care workers in the Philippines have tested positive for SARS-Cov2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Twenty six have already died.

The World Health Organization has found the increasing number of Filipino health care workers who have COVID-10 “very worrisome,” but the Department of Health has shot down assertions that the steep number of health care workers contracting COVID-19 is due to PPE shortage.

The alarming shortage of PPE for Filipino health care workers drew national attention through social media, prompting a slew of donations from Good Samaritans in March, with help pouring in from small establishments, large corporations, celebrities and those who would rather remain anonymous.

With a laser-cutting machine at their disposal, Luzon and his staffers, who had been stuck with him since the start of the enhanced community quarantine (ECQ), set out to manufacture more aerosol boxes to be given for free to hospitals nationwide.

Like Dr. Mardo, Luzon used the power of social media and crowdsourced the availability of materials. In no time, his e-mail inbox was flooded with messages from all over the country, as well as from OFWs abroad, all pledging to help him make more aerosol boxes.

It was an initiative that, for lack of a better term, went viral and one that soon overwhelmed Luzon’s team of seven people, who realized it could only produce 10 to 15 aerosol boxes a day.

Aerosol boxes ready for pickup and delivery. Image: Facebook/Jao Achie

“The number of people who donated was overwhelming, there was a lot of excess material for my team,” said Luzon in Filipino.

As the project progressed, Luzon sought the help of other business owners for help in cutting parts of the boxes and assembling these. He connected with a group of workers in the cities of Caloocan and Paranaque, most of whom lost their jobs because of the ECQ.

“They were the ones who messaged me who said paying them just so they would have food, rice, or milk for their child would already be enough,” Luzon said.

“But of course, through their effort, their initiative to help already means a lot, even before they asked for payment,” he added.

Luzon said his team has already manufactured over 900 aerosol boxes as of April 15, less than a month since they started the initiative. It takes around 30 minutes for the machine to cut the clear acrylic and another 15 to 20 minutes to assemble the boxes.

Had Luzon limited the manufacturing to just his team, production would be just around 200 boxes. But now, his team is able to assemble at least 50 boxes per day with the help of business owners and workers.

They have since called the initiative Hope in a Box.

Aerosol boxes ready for pickup and delivery2. Image: Facebook/Jao Achie

The aerosol boxes have since been donated to hospitals all over the country, some in Baguio, Nueva Vizcaya, Nueva Ecija, Lucena, and Bicol, and more in provinces in Visayas and Mindanao.

In the beginning, Luzon ran into challenges that threatened to disrupt the manufacture of the aerosol boxes.

He recalled some business owners, who got wind of the need for the boxes, started to hoard sheets of acrylic from suppliers, thinking they could profit from making the boxes themselves.

This forced Luzon to look for other suppliers of acrylic sheets to fight the hoarding.

He eventually found one he could trust who even lowered prices and refused to sell to hoarders, those who would sell the aerosol boxes instead of donate these.

Luzon recalled hordes of vehicles appearing in front of his office in the initial release of aerosol boxes.

They came to volunteer to deliver the boxes to hospitals that needed the items—private individuals, transport service groups and even personnel of the Metropolitan Manila Development Authority.

He hadn’t foreseen the sheer number of private cars and other vehicles that would show up all at the same time to pick up aerosol boxes for delivery.

Learning from his mistake, Luzon saw the wisdom of scheduling the pickup of the boxes on a daily basis, setting times for each pickup to avoid vehicles clogging the street in front of his office.

Luzon and his team, thanks to the donations of Filipinos, also plan to install enclosed tents for overcrowded hospitals. Image: Facebook/Jao Achie

“At first I was shocked. It was the first release of the aerosol boxes, there were so many vehicles in front here,” Luzon recalled, speaking in Filipino.

“I said, ‘This is wrong, wrong, wrong,’ because I failed to consider social distancing,” he said.

“There really was traffic here in our area in the beginning,” said Luzon.

“Now, we first contact those who will be doing the pickup and delivery. We’ll bring the boxes out in the front so they can do the pickup and loading themselves,” he said.

Luzon’s team and his network of fabricators still continue to manufacture aerosol boxes for health workers, but they have also expanded to making face shields and swab test barriers or walls, also made of acrylic, which serve as added protection for health workers when they perform swab testing for the virus.

On April 14, Luzon’s team installed its first 12 x 24 enclosed tent at the Mandaluyong City Medical Center, which would cater to patients who can no longer be accommodated inside the hospital due to overcrowding. More tents can be set up, he said, as long as these are needed.

Now, he’s looking forward to creating protective suits and other PPE for the health workers and already has plans to link up with tailors and seamstresses for help.

Ending the work hasn’t crossed Luzon’s mind yet. Not now, and perhaps not anytime soon.

“Maybe I won’t stop helping until this is over. I’ve already started,” he said in Filipino.

-With reports from Daphne Galvez, Doris Dumlao-Abadilla, Ben O. de Vera, Melvin Gascon, Dona Z. Pazzibugan and Jodee A. Agoncillo