Jeers, laughs and tears at Imelda docu screening

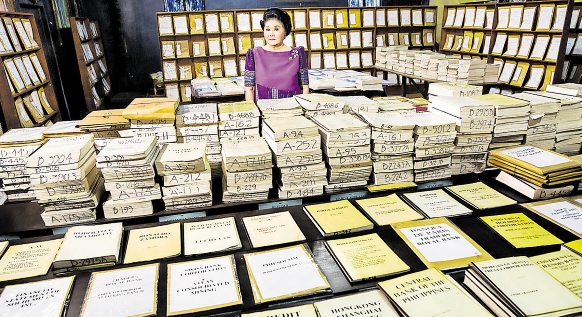

PAPER TRAIL A scene from the “The Kingmaker’’ shows Imelda Marcos and piles of court

documents, including those on graft cases that ended in her conviction in November 2018 and

for which she was sentenced to a maximum prison term of 77 years. Allowed to post bail and

with her cases on appeal, the 90-year-old widow of dictator Ferdinand Marcos has yet to spend even an hour behind bars. LAUREN GREENFIELD

The camera does not lie.

In “The Kingmaker,” a 2019 documentary on graft convict and former first lady Imelda Marcos, the camera captures many untruths, or half-lies, on the turn of events following the election of her husband Ferdinand Marcos as Philippine president in 1965, the ascendancy of the “conjugal dictatorship,” and her efforts to groom her only son, Bongbong Marcos, to become president himself.

Right off the bat, as the film crew tails her on a drive around Manila, Imelda takes note of the squalor and poverty and pronounces that this was not the case during her time.

But records of the social, economic and policy research foundation Ibon contradict her claim. The unemployment rate in the Philippines, for one, rose from 7.1 percent in 1965 to 12.6 percent in 1985, just before the Marcos family fled to Hawaii.

In addition, Ibon documents show, the rate of inflation, or the rise in prices of goods and the drop of the purchasing value of the peso, was at 2.7 percent in 1965 but soared to 23.2 percent in 1985. And in 1985, after years of the Marcos family’s excesses, the “official poverty incidence” was at a whopping 49 percent.

Article continues after this advertisementIn a light moment in the documentary, Imelda, now 90 years old, is caught telling her assistant before the cameras rolled that she has become less than svelte: “Ang tiyan ko, halata bang malaki?”

Article continues after this advertisementThe assistant replies that it doesn’t show: “Ma’am, hindi raw po halata.” The camera then passes over Imelda’s bloated belly.

Beyond the shoes

During the 7 p.m. screening on Jan. 29 at the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP), shouted expletives are heard from the audience whenever Imelda is shown saying something outrageous.

The idea of making the documentary, says its writer and director, Lauren Greenfield, was spurred by her interest in Imelda Marcos beyond the thousands of pairs of shoes the latter left behind in the family’s haste to escape the February 1986 Edsa People Power Revolt, and by a 2013 article by William Mellor on Calauit Island in Palawan, on which the dictator put up a private wildlife park featuring more than 100 animals including giraffes flown in from Kenya.

But after starting filming in 2014, the American filmmaker-photographer says in an open forum with the CCP audience via Skype after the screening, she realized that her project was morphing into something else, with a bigger scope that would encompass Imelda’s desire to get back in power by backing the candidacies of Rodrigo Duterte and her son Bongbong for president and vice president in the 2016 elections. Hence the documentary’s title.

Power behind the throne

Imelda recalls her visits to the United States, Russia, China and other countries to highlight her role as the power behind her husband’s throne. At one point, she quotes Mao Zedong as whispering in her ear that in five minutes, she could “end the Cold War.”

But in stark contrast to the Marcoses’ image of benevolent monarchs during martial law, the docu presents former political detainees as living witnesses to the regime’s crimes.

The camera lingers on Etta Rosales and May Rodriguez recalling the sexual abuse they endured while under military custody. Rodriguez’s narration, which moved many a viewer to tears, includes graphic detail of her violation, with one of her interrogators claiming that she might be hiding incriminating documents in her private parts.

Money in 170 banks

In an eye-popping scene, Imelda shows voluminous documents presented in court as evidence of the charge of graft against her and her husband.

The names and corporations that the eye can catch as the camera pans have been proven to be complicit with the couple.

In November 2018, the antigraft court Sandiganbayan convicted Imelda of seven counts of graft, each with a sentence of imprisonment. She was ordered arrested but the Philippine National Police hedged, and eventually she was allowed to post bail.

Near the film’s end, Imelda’s claim that she has a lot of money in “170 banks” elicits a roar of laughter from the audience.

That particular statement bothered Greenfield, so much so that she declares: “Imelda Marcos is an unreliable storyteller.” She adds that she had to verify the veracity of the 170 banks with Andres Bautista, a former chair of the Presidential Commission on Good Government (PCGG), who also appears in the docu.

Bautista says that when the PCGG raided one of the residences where Imelda shows off expensive paintings in the docu, the same artworks were nowhere to be found.

History lesson

That “The Kingmaker” is an important work that serves as history lesson for the young generations can’t be overstated, as CCP vice president and artistic director Chris Millado says in his keynote address before the screening.

Explaining the decision to screen the docu in a structure credited as an Imelda Marcos project, Millado points out that it was only after the Edsa People Power Revolt that the CCP expanded its programs to include marginalized sectors and artistic expression.

“The CCP was founded in 1969, but it was born in 1986,” he says, quoting the award-winning writer Resil Mojares.

Millado delivers the coup de grace in expressing the hope that “The Kingmaker” will serve as “an inspiration on how we can harness the potency of art to combating this spreadable virus—the virus of idiocy and indifference.”