Iran state TV says ‘rioters’ shot and killed amid protests

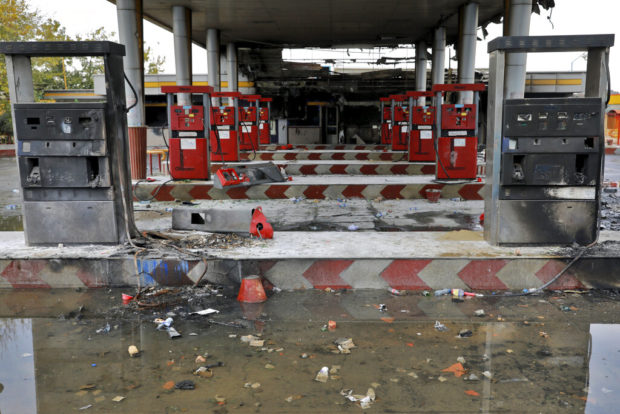

In this Nov. 20, 2019, file photo, rainwater pools at a gas station attacked during protests over government-set gasoline prices in Tehran, Iran. Amnesty International says at least 208 people in Iran have been killed amid protests over sharply rising gasoline prices and a subsequent crackdown by security forces. The country has yet to release any nationwide statistics about the unrest last month. AP

DUBAI — Iranian state television on Tuesday acknowledged security forces shot and killed what it described as “rioters” in multiple cities amid recent protests over the spike in government-set gasoline prices — the first time that authorities have offered any sort of accounting for the violence they used to put down the demonstrations.

The acknowledgment came in a television package that criticized international Farsi-language channels for their reporting on the crisis, which began on Nov. 15.

Amnesty International said Monday it believes at least 208 people were killed in the protests and the crackdown that followed. Iran’s mission to the United Nations disputed Amnesty’s findings early Tuesday, though it offered no evidence to support its claim.

Iran has yet to release any nationwide statistics over the unrest that gripped the Islamic Republic with minimum prices for government-subsidized gasoline rising by 50%.

Iran shut down internet access amid the unrest, blocking those inside the country from sharing their videos and information, as well as limiting the outside world from knowing the scale of the protests and violence. The restoration of the internet in recent days across much of the country has seen other videos surface.

Article continues after this advertisement“We’ve seen over 200 people killed in a very swift time, in under a week,” said Mansoureh Mills, an Iran researcher at Amnesty. “It’s something pretty unprecedented event in the history of the human rights violations in the Islamic Republic.”

Article continues after this advertisementWhile not drawing as many Iranians into the streets as those protesting the disputed 2009 presidential election, the gasoline price demonstrations rapidly turned violent faster than any previous rallies. That shows the widespread economic discontent gripping the country since May 2018, when President Donald Trump imposed crushing sanctions after unilaterally withdrawing from Tehran’s nuclear deal with world powers.

The state TV report sought to describe killings in four categories, alleging some of those killed were “rioters who have attacked sensitive or military centers with firearms or knives, or have taken hostages in some areas.” The report described others killed as passers-by, security forces and peaceful protesters, without assigning blame for their deaths.

In one case, the report said security forces confronted a separatist group in the city of Mahshahr armed with “semi-heavy weapons.”

“For hours, armed rioters had waged an armed struggle,” the report alleged. “In such circumstances, security forces took action to save the lives of Mahshahr’s people.”

Mahshahr in Iran’s southwestern Khuzestan province was believed to be hard-hit in the crackdown. The surrounding oil-rich province’s Arab population long has complained of discrimination by Iran’s central government and insurgent groups have attacked area oil pipelines in the past there. Online videos purportedly from the area showed peaceful protests, as well as clashes between demonstrators and security forces.

State TV separately acknowledged confronting “rioters” in Tehran, as well as in the cities of Shiraz and Sirjan. It also mentioned Shahriar, a suburb of Tehran where Amnesty on Monday said there had been “dozens of deaths.” It described the suburb as likely one of the areas with the highest toll of those killed in the unrest. Shahriar has seen heavy protests.

Amnesty offered no breakdown for the deaths elsewhere in the country, though it said “the real figure is likely to be higher.” Mills said there was a “general environment of fear inside of Iran at the moment.”

“The authorities have been threatening families, some have been forced to sign undertakings that they won’t speak to the media,” she said. “Families have been forced to bury their loved ones at night under heavy security presence.”

Authorities also have been visiting hospitals, looking for patients with gunshot wounds or other injuries from the unrest, Mills said. She alleged that authorities then immediately detain those with the suspicious wounds.

Iran’s U.N. mission in New York called Amnesty’s findings “unsubstantiated,” without elaborating.

“A number of exile groups (and media networks) have either taken credit for instigating both ordinary people to protest and riots, or have encouraged lawlessness and vandalism, or both,” said Alireza Miryousefi, a spokesman at the mission.

The demonstrations began after authorities raised minimum gasoline prices by 50% to 15,000 Iranian rials per liter. That’s 12 cents a liter, or about 50 cents a gallon. After a monthly 60-liter quota, it costs 30,000 rials a liter. That’s nearly 24 cents a liter or 90 cents a gallon. An average gallon of regular gas in the U.S. costs $2.58 by comparison, according to AAA.

Cheap gasoline is practically considered a birthright in Iran, home to the world’s fourth-largest crude oil reserves despite decades of economic woes since its 1979 Islamic Revolution. Gasoline there remains among the cheapest in the world, in part to help keep costs low for its underemployed, who often drive taxis to make ends meet.

Iran’s per capita gross domestic product, often used as a rough sense of a nation’s standard of living, is just over $6,000, compared with over $62,000 in the U.S., according to the World Bank. That disparity, especially given Iran’s oil wealth, fueled the anger felt by demonstrators.

Already, Iranians have seen their savings chewed away by the rial’s collapse from 32,000 to $1 at the time of the 2015 nuclear accord to 126,000 to $1 today. Daily staples also have risen in price.

The scale of the demonstrations also remains unclear. One Iranian lawmaker said he thought that over 7,000 people had been arrested, although Iran’s top prosecutor disputed the figure without offering his own.

Meanwhile, Mir Hossein Mousavi, a long-detained opposition leader in Iran, compared the recent crackdown by security forces on protesters to soldiers who in the time of Iranian Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi gunned down demonstrators in an event that led to the Islamic Revolution. His comparison raised the rhetorical stakes surrounding the latest unrest.