How a Japanese ‘spin master’ stays at the top of his game

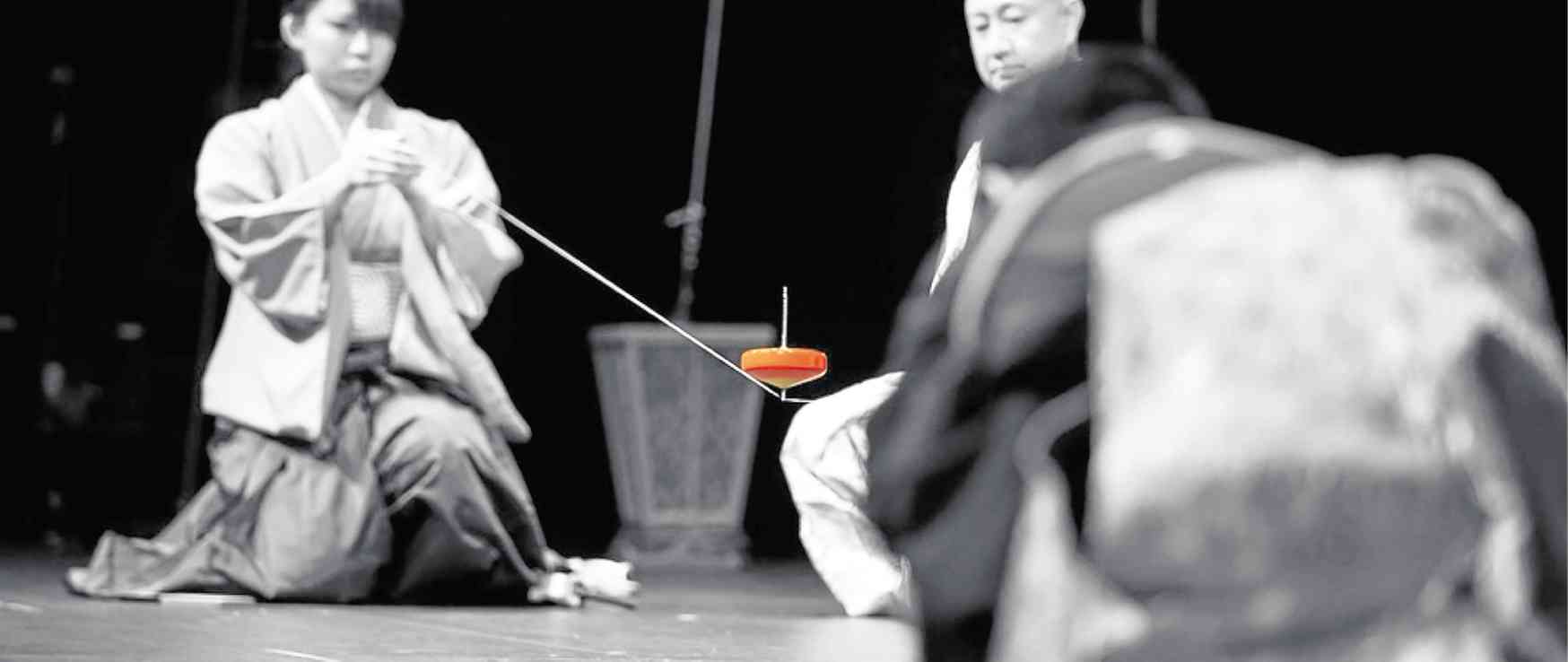

BALANCING ACT Shuraku Chikushi (right) and his “disciples” show how Japanese tops can be spun on a stick or on the palm of one’s hand.

HAKATA, Japan — Shuraku Chikushi is not a rock star, a virtuoso pianist or an acrobat. Neither is he an illusionist.

But he performed before the Japanese royal family, Queen Elizabeth of England, former US President Barack Obama and other world leaders, and at the G-20 Summit in Osaka, in June.

The roving showman of sorts performed in 24 countries, along with his mother, wife, sister and a few “disciples.”

Shuraku, 44, is a maker and spinner of tops (“trumpo”), and a 20th generation master who has been keeping the art of Chikuzen Hakata “koma” (spinning tops) alive.

His mastery of this performance art has earned him the title Hakata’s “best top performer,” a designation first bestowed by Japan’s emperor in the 17th century.

Article continues after this advertisementThe Fukuoka Prefecture itself has designated spinning Hakata koma as an intangible cultural asset, and making tops a traditional handicraft.

Article continues after this advertisement

PERFORMANCE ART It takes years to master different techniques of spinning a top, like sliding one on a string. —PHOTOS FROM WWW.HAKATA-KOMA.JP

Yin and yang

There are 23 techniques in spinning the toy, Shuraku said, adding that it is a balancing act that involves yin and yang, and such props as swords, fans, poles and strings.

Shuraku can spin the toy along the edge of a katana (sword) and a string, among other tricks.

At the Hakata Machiya Folk Museum, where he guided three journalists on Sept. 11 to paint a top with different colors, Shuraku said he would pass on the art of making and spinning tops to his son.

Tutored in the art form by his mother when he was a boy, he said he would start teaching his son, now just 1-year-old, when the boy reaches the age of 3.

Before they get to be 10 years old, selected children are taught three techniques in spinning tops. By age 10, the student is expected to have mastered five, Shuraku said.

To be proficient in a technique takes two years.

Letting a top slide along the edge of a sword, however, takes three to four years to master, he said.

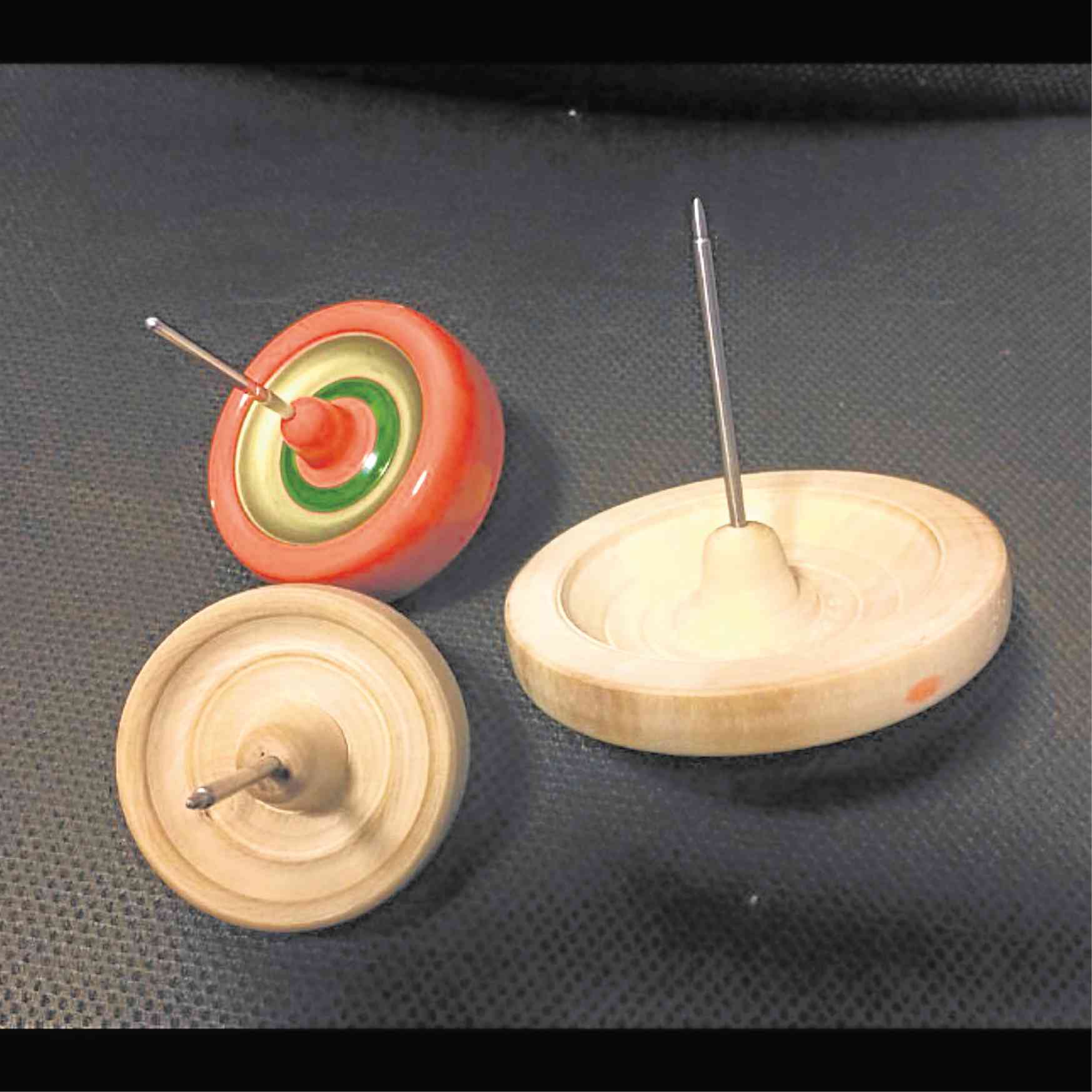

LIKE FLYING SAUCERS Japanese tops shaped like flat disks are multicolored and come in various sizes.

Traditional woodcraft

Shuraku keeps the traditional art form alive by going to a workshop at the Hakata Machiya Folk Museum every Wednesday to demonstrate before visitors the traditional woodcraft.

Schools in Hakata have extended a helping hand in preserving the tradition, introducing it to 6- to 12-year-old pupils.

“I’m glad to see many children playing tops,” Shuraku said.

But the number of those doing so have shrunk in recent years and it is now taking longer for pupils to learn the art, he noted.

“Children have become more clumsy compared to olden days,” Shuraku said through a translator, something that makes him kind of sad.

Spinning tops is a traditional game played in many countries, including the Philippines. But with children now exposed to a cornucopia of digital games available on the internet, the game is fast losing its appeal.

The wooden tops that Shuraku makes are shaped like flying saucers. In the Philippines, tops are spherical in shape, with a tapering bottom where the leg (usually a nail) is attached.

As a boy, I played tops made of wood from the guava tree by throwing the toy to the ground with a vertical handstroke. In contrast, Shuraku releases the top from his hand in a horizontal stroke.

Merchant district

Koma spread from China to Hakata, an ancient trading port that was Japan’s gateway to countries to its west.

Hakata, a merchant district, merged with the adjacent Fukuoka, home to many samurai, in 1889, with the latter becoming the name of the new entity upon the insistence of the samurai.

Fukuoka’s location in the northwestern part of Kyushu puts it nearer to Seoul in South Korea and Shanghai in China, than Tokyo.

This location made Fukuoka a target of Kublai Khan, who in the 13th century tried—but failed—to invade northern Kyushu twice—first in 1274 with a fleet of hundreds of ships and tens of thousands of troops, and in 1281, with more than a hundred thousand soldiers and a few thousand ships.

Typhoons or “kamikaze” (divine wind) destroyed the invading forces on both occasions, saving Japan from the Mongol horde.

Part of the 20-kilometer long-stone barrier built by samurai after the first Mongol invasion attempt still stands in Fukuoka, said Akiko Takamura, a press officer of the Fukuoka Museum.

Also on display at the museum were scores of exquisitely preserved sword blades from all over Japan and body armors from the 11th to the 17th century.

At the science museum in another part of the city, exhibits are interactive — from the cell structure of a bark seen under a microscope, a plane’s flight simulation, and the shaking of chairs due to different types of movement of the earth’s crust when earthquakes strike, to images of the planet from different heights and depth.

Fukuoka Prize

Grounding schoolchildren in their history and in science, as well as drilling principles, such as “jiritu” (self-control and self-discipline), “keiai’ (care and respect for one another), and “kinben,” (hard work) into them have helped make Fukuoka and Japan a modern society anchored on its traditions.

These principles are the three objectives of the Matsuzaki Junior High School in Fukuoka City, its principal Masuda Mizuho told Dutch historian Leonard Blusse, an awardee of the 2019 Fukuoka academic prize. Blusse gave a talk on Sept. 12 to some 530 students on the Netherlands’ maritime trade with Japan and China in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Haruyoshi Junior High School — where Randy David, the first Filipino to win the Fukuoka grand prize, gave a talk on Sept. 13 — seeks to instill “reijo” (courtesy), “shingi” (keeping faith in oneself) and kinben in its 563 pupils.

Over the past 30 years, the grand prize winners of the Fukuoka Prize—which promotes peace and respect as well as tolerance for the diversity of Asian culture — include Ravi Shankar of India, Pramoedya Ananta Toer of Indonesia, Ezra Vogel of the United States, Muhammad Yunus of Bangladesh and Zhang Yimou of China.