Dynasties: ‘Thin’ can fit in; ‘fat’ is that bad

MANILA, Philippines — Thin is in even in political dynasties, and obesity is where you draw the line.

And regulation, not prohibition, is a more practical and politically viable way to deal with them, senior economist Ronald Mendoza said on Tuesday as deliberations began in the Senate on the antipolitical dynasty bill.

According to Mendoza, who is also dean of the Ateneo School of Government, the electoral playing field should be leveled for everyday Filipinos by eliminating “fat” dynasties, or families with two or more members simultaneously occupying elective positions.

He drew a distinction between fat and “thin” dynasties, or families with members that follow each other in elected positions over time.

Continuing expansion

“There’s still democracy when families choose to succeed each other only one at a time,” Mendoza said. “But when they capture many local positions at the same time, that is when unintended consequences pervade politics. Give a chance to others. Our democracy is not a family business.”

Mendoza’s arguments, which he presented during the public hearing on the antidynasty bill by the Senate committee on electoral reforms and people’s participation, stem from the study that he conducted with Leonardo Jaminola and Jurel Yap of the Ateneo Policy Center (APC).

Findings from their working paper, “From Fat to Obese: Political Dynasties After the 2019 Midterm Elections,” which was published online on Sept. 1, show that fat dynasties continue to expand—and many have become “obese” over the past 30 years.

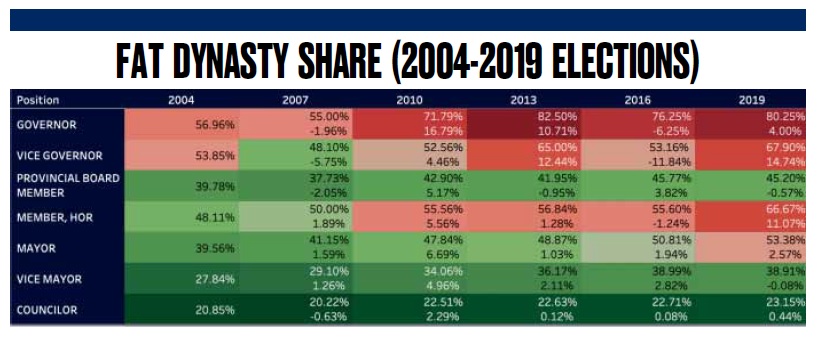

By analyzing the APC’s political dynasties data set, covering the period from 1988 to 2019, the researchers found that the share of fat dynasties increased from 19 percent of all local elected officials in 1988 to 29 percent in 2019, growing at about 1 percent, or around 170 positions, per election period.

In 2004, around 57 percent of governors came from fat dynasties. This has risen to over 80 percent of governors by 2019.

Among congressmen, fat dynasties accounted for 48 percent in 2004, rising to 67 percent by 2019, and mayors from 39 percent in 2014 to 53 percent in 2019.

Weakened checks and balances

“The research suggests that more fat dynasties weaken checks and balances in our democracy, leading to bad governance, and consequently weaker development outcomes,” Mendoza said.

He said a law similar to Republic Act No. 10742, or the Sangguniang Kabataan (SK) Reform Act, could help free up 25 percent of local elected positions for new political leaders.

Under the SK Reform Act, qualified SK aspirants must not be related within the second civil degree of consanguinity or affinity to any incumbent national or local official in the place where they seek to be elected.