Wartime tunnel to turn into museum

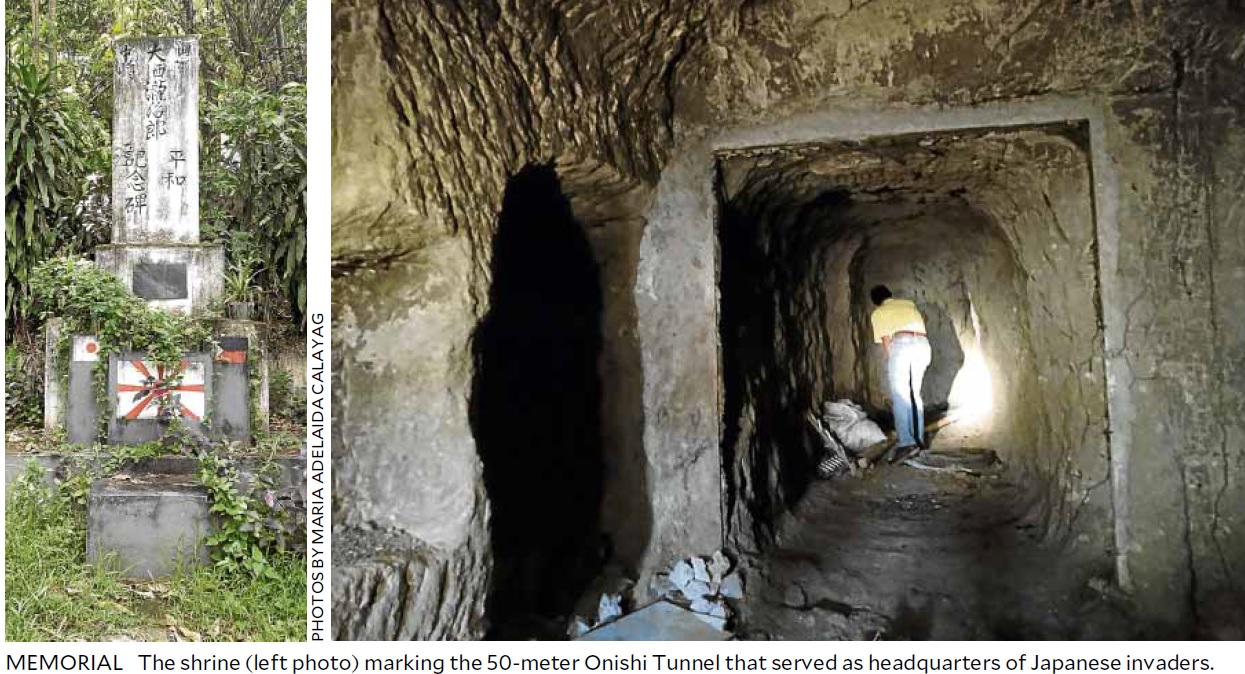

Called “Onishi Tunnel” or “Onishi Shrine,” the tunnel is located at Sitio Panaisan in Barangay San Nicolas here.

It used to serve as a communications office and naval headquarters of the Japanese Imperial Army that occupied the Philippines during World War II.

American soldiers and Filipino guerrillas failed to detect its presence in the mountains.

Tutorial for schoolchildren

It is now being transformed into a museum by its owner, Louie Balceda, who hopes to establish a tutorial for schoolchildren about World War II.

Article continues after this advertisementBalceda has put up an 80-seat hut, surrounded by large speakers, near the 50-meter communications tunnel that leads to a 66-meter deep reservoir.

Article continues after this advertisement“I am not too concerned that my surroundings may soon be occupied with buildings. If the community will soon host the New Clark City, I will retain a jungle around the tunnel. I plan to dress up tour guides as Japanese soldiers. We will have documentaries to show children what the war was all about,” Balceda said.

The tunnel was named after Vice Adm. Takijiro Onishi, a tactician who founded the Kamikaze, a squadron of Japanese fighter pilots who were so devoted to their country they volunteered to crash their planes on American warships.

The Japanese soldiers were originally stationed at Nichols Air Field in Manila in October 1944.

On Nov. 19 of the same year, the occupying forces moved their headquarters to the twin mountains here that were called Kambal a Bunduk.

All reports and military orders issued in the country were transmitted from the tunnel, which was manned by “tsushintai” personnel who encoded top secret messages.

Atonement

These men were usually shirtless due to the heat in the tunnel and many were emaciated because they subsisted on small food rations.

Onishi took his own life with a “katana” (a short Japanese blade) on Aug. 16, 1945, leaving behind a poem signifying that he took responsibility for the death of Kamikaze pilots, according to Rhonie de la Cruz, curator of the Bamban Historical Museum.

In 2001, De la Cruz visited Onishi’s former aide, Moji Chikanori, who asked him to offer flowers at the tunnel on behalf of the Japanese war veterans.

De la Cruz instead put up the shrine to honor soldiers of Japan’s First and Second Air Fleet who died in the war.

About 500 Japanese visitors attended the ceremony when the shrine was launched in 2001.

A Japanese remembers

In 2003, a “torii” gate was built at the entrance to the shrine.

Japanese tourists who visit and pray at the shrine sometimes kiss the ground before entering.

Although memories of Japanese atrocities linger 77 years after the war, one of Tarlac’s oldest residents remembers one Japanese with fondness.

Erlinda Manalo Tan, 83, said she befriended Capt. Kanehiro Imamura when she was 7 years old. Imamura was stationed at the Bamban sugar central from 1944 to 1945 and sent candies to Tan.

“I think I reminded him of his own daughter back in Japan. He was very nice to me,” Tan said.

Her brothers were employed at the time by a Japanese official named Yamaguchi, so the family fared better during the war.

One brother handled the laundry while another managed the horses of Yamaguchi, who was described as the most feared official of the dreaded Kempeitai, the Japanese military police.

Two more brothers worked in Toyomenca, a cotton plantation.

They were directed to flee when news spread that Allied forces would soon bomb Tarlac.

Tan said the guerrillas helped her family pack their belongings and evacuate.

But before leaving, Imamura gifted her with a pair of doves.

Imamura survived the war and visited the country in the early 1970s but failed to meet Tan.

He, however, reconnected with her through letters he wrote with the help of a Tokyo professor who spoke English.