Settlers want to turn forest protectors

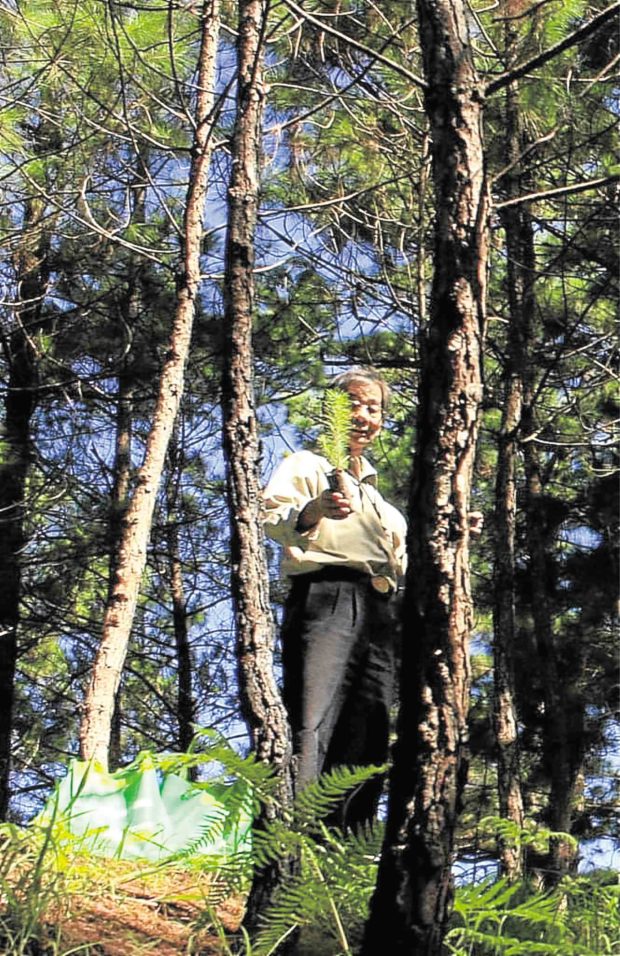

PINE PATCH Busol watershed is vital to sustaining Baguio City’s water supply. The late Ramon Dacawi (in photo), one of the founders of the environmental program “EcoWalk,” brought groups of students to this patch of pine forest to teach them about the value of trees. —PAUL RILLORTA / CONTRIBUTOR

BAGUIO CITY, Benguet, Philippines — Facing eviction, Ibaloy land claimants and settlers have offered to secure and preserve the 336-hectare Busol watershed, the city’s key source of potable water that has been threatened by encroachment for decades.

The offer was made last week during a meeting called by city officials, who were poised to demolish eight new structures built within the Busol forest reserve, which Baguio shares with neighboring La Trinidad town in Benguet province.

The city intends to resolve squatting on 112 ha of the watershed within its territory as it begins a conservation and rehabilitation program for its remaining 2.5 million trees, Mayor Benjamin Magalong told 200 Busol residents who attended the meeting.

Busol was segregated for the conservation and protection of Baguio water and timber resources in April 1922 through a proclamation.

Water rationing

Article continues after this advertisementIt remains vital because potable water in the city has been rationed since the late 1980s. The Baguio Water District (BWD) taps Busol for water that is supplied to 30 percent of the city’s about 350,000 residents.

Article continues after this advertisementBut Magalong suspended the demolition after dwellers agreed to organize, police their ranks and put together plans for protecting the forest.

The city did not give the number of Busol dwellers, although foresters and the BWD in 2007 listed 695. An inventory conducted in 2006 by a Busol task force, composed of local and national forest regulators, said 643 houses were built in the Baguio part of the watershed at the time while 532 houses were constructed in La Trinidad.

Many dwellers were granted approved land surveys and were issued tax declarations, so the government and the environmental group Baguio Regreening Movement (BRM) launched a public campaign to fence off the watershed.

Legal conflict

But the fencing project was blocked in 2009 when Busol became the center of a legal conflict between Ibaloy land claimants and the city government.

Ibaloy families asserted their ancestral land rights and claims, prompting the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP) to stop all fencing activities.

Families belonging to the Molintas and Gumangan clans said their ancestors’ names were identified as claimants.

The city government cited a provision in the Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act of 1997 (Ipra, or Republic Act No. 8371), which exempted Baguio from the law’s coverage.

In an Aug. 30, 2012, letter to the NCIP, the city government opposed ancestral land applications filed in Baguio, except those recognized by the government before Ipra was enforced.

In 2018, the Supreme Court ruled against the claimants.

Magalong, during the meeting with settlers, said that while Ibaloy families could continue to pursue their claims, the high court had clearly established that the watershed could not be inhabited. —Vincent Cabreza