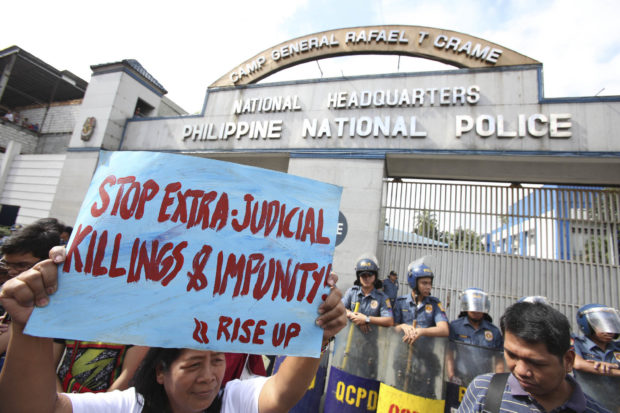

Militants call for an end to summary killings linked to the Duterte administration’s campaign against illegal drugs during a rally in January 2017 outside the PNP headquarters at Camp Crame in Quezon City. (File photo by NIÑO JESUS ORBETA / Philippine Daily Inquirer)

MANILA, Philippines — The rising number of direct attacks on civilians in the Philippines despite the absence of “large-scale conventional war” caught the attention of researchers in a United States-based group because it exceeded the figures in countries where armed conflict was widespread, according to the group’s research director.

Dr. Roudabeh Kishi, head of research at Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (Acled), said in an e-mail to INQUIRER.net that “the fact that the Philippines — a country not in the midst of a large-scale conventional war — reports higher levels of direct civilian targeting this year (2019) than contexts like Afghanistan or Somalia with active warfare is quite damning.”

“Other countries — like Nigeria, the DRC [Democratic Republic of Congo] or countries in the Sahel (Desert) — may dominate international headlines but it is important to remember that civilians in the Philippines continue to be at heightened risk,” said Kishi, who oversees the work of Acled on research and data-gathering about conflicts worldwide.

In a 2019 report, Acled said nearly 490 civilians were killed in the Philippines as a result of a “wave of targeted attacks” which meant the fatalities were the actual targets and not just part of so-called collateral damage. The group counted at least 450 such attacks in the Philippines since the start of 2019.

The report said at least three-fourths or 75% of attacks were related to President Rodrigo Duterte’s bloody campaign against illegal drugs and crimes which he launched immediately upon assuming power in 2016 to fulfill a campaign promise to eradicate the drug menace within six months. He later admitted it wasn’t possible.

According to Kishi, the report was “prompted by the fact that violence against civilians has continued unabated in the Philippines through the first half of 2019.”

“This violence…and persistent reports of extrajudicial killings helped bring new attention to the crisis,” she said.

“Drawing conclusions from our data, we find confirmation for the wave of targeted attacks, resulting in the reported deaths of 490 civilians since the start of the year [2019],” said Kishi.

The Philippines was fourth on a list of most dangerous countries for civilians next only to Yemen, a country torn by civil war. The most dangerous country on that list was India followed by Syria.

In the Philippines, Acled said it found that “state forces have been the primary perpetrators” of targeted attacks on civilians largely as a result of the enforcement of the anti-drug campaign by the Philippine National Police (PNP).

The President had given police a supporting role in the campaign following outrage over the murder of a Korean businessman inside the PNP headquarters in Crame in Quezon City in a rogue police operation that entailed abducting moneyed individuals, tagging them as drug suspects, and keeping them captive until they or their families paid up what was tantamount to ransom.

Kishi said Acled collects data and information on conflicts and their impact on civilian populations in at least 90 countries that included the Philippines. Acled, she said, “covers political violence and disorder in the Philippines.”

These pieces of information, she said, are put together on a weekly basis and go through three rounds of review before the data are published.

So Acled’s data and information on civilians in the crosshairs in the Philippines was just a factual statement and did not involve political views as the Duterte administration painted human rights reports to be.

In its 2018 annual report on violence against civilians worldwide, it said “the Philippines is a war zone in disguise.”

“More civilians were killed in the Philippines in 2018 than in Iraq, Somalia or the Democratic Republic of Congo,” the report said.

It said it highlighted the “lethality” of Duterte’s campaign against drugs. “Throughout the year [2018] the Philippines saw similar levels of civilian fatalities stemming from direct civilian targeting as Afghanistan,” the annual report said.

Kishi said while Acled is “not an advocacy organization, we see these reports as a plain statement of facts.”

Last July 11, United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) passed the Iceland resolution asking UN rights chief Michelle Bachelet to conduct an investigation into the human rights situation in the Philippines.

The resolution drew harsh reactions from the Duterte administration and some lawmakers. The reactions ranged from the absurd — a senator offering to be beheaded if allegations of state-sponsored killings were proven true — to the irrelevant — the Senate President condemning nations that allow abortions for voting for the resolution and having no moral ground to investigate the drug war killings in the Philippines.

But human rights advocates welcomed the UNHRC resolution. Some harked back to statements made by the late US Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan who said: “The amount of violations of human rights is always an inverse function of the amount of complaints about human rights violations heard from there. The greater the number of complaints being aired, the better protected are human rights in that country.”

/atm