Challenges hound efforts for cleaner public transport to curb pollution

PERSISTENT PROBLEMS The Department of Environment and Natural Resources sees merit in the shift to Euro-4 compliant vehicles. But as long as secondhand or dilapidated cars are on the road, efforts of the Anti-Smoke Belching Unit and even Private Emissions Testing Centers will make no sense because the problems are already out there, experts say. —INQUIRER FILE PHOTO

(Last of three parts)

MANILA, Philippines — Like many commuters, Ashley Usman has had her fair share of harrowing experiences riding public transport.

She recalled taking two jeepney rides daily while reviewing for the engineering board exams in 2013, and braving the gauntlet of people and vehicles clogging Morayta Street at the university belt in Manila.

“During that review period, I had intense eye allergies and had to have a surgery on my left eyelid,” said Usman, a chemical engineer who hails from Lanao del Norte province. “The doctor said it was due to poor air quality.”

So as soon as Usman got a job in Bataan province, she decided that the metropolis was just not worth it, both for her health and safety.

Article continues after this advertisement“If Metro Manila’s air gets better, then I’d definitely consider working there,” she said. “But in just a year [of working in Bataan], I already felt the big difference … particularly in the air quality.”

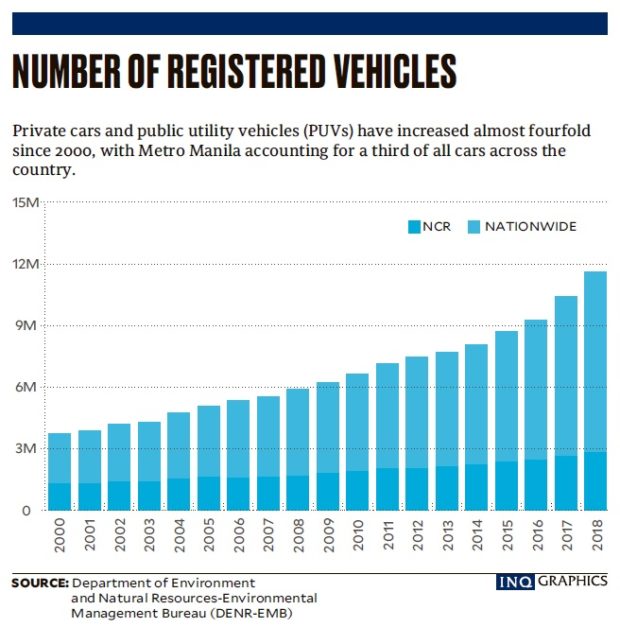

Article continues after this advertisementWith 16 cities and one town, Metro Manila is beset with issues and challenges that come with rapid urbanization, from overpopulation to unequal development. The economic growth seen in the skyscrapers and paved roads comes at a steep price: air pollution from the toxic fumes spewed by thousands of vehicles on the road.

Clean Air Act

In Metro Manila, 88 percent of all emissions come from motor vehicles, a problem that the 20-year-old Clean Air Act, despite its best intentions, has failed to curb.

Under the 1999 law, the Department of Transportation (DOTr) is mandated to reduce emissions from motor vehicles to within acceptable guidelines. But it was only in 2017 that the agency began its aggressive push for its ambitious Public Utility Vehicle Modernization Program (PUVMP).

The program aims to phase out dilapidated PUVs, including jeepneys that are over 15 years old, and shift to Euro-4 compliant and industry-standard vehicles.

Studies have shown that Euro-4 gasoline is 90 percent cleaner than its Euro-2 counterpart, thanks largely to its composition, and the way Euro-4 engines are designed, said Gerry Bagtasa, head of the Atmospheric Physics Laboratory of the University of the Philippines’ Institute of Environmental Science and Meteorology (UP IESM).

Martin Delgra, chair of the Land Transportation Franchising and Regulatory Board (LTFRB), acknowledged that the agency, along with the DOTr, through the Land Transportation Office (LTO), had for the longest time “fallen short of the requirements” of the Clean Air Act.

But beyond giving the PUVs a face-lift, Delgra said the PUVMP is a “radical restructuring” of the public transport system that needs a consolidation of PUV fleets and route rationalization.

Much of the woes in public transport are rooted either in the haphazard way routes are designed, the over- or undersupply of PUVs in certain areas, or the vehicles’ lack of interconnection, making it difficult to commute, Delgra said.

Resolving those problems will enable the government to reform urban spaces and make public transport more efficient, he added.

Sustainable transport

“The PUVMP program is not just a big help but a huge statement in creating sustainable transport,” Delgra said. “We are not just deploying new environment-friendly PUVs, but also trying to make them efficient.”

The Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), as the lead department in enforcing the Clean Air Act, sees the merit in the shift to Euro-4 compliant vehicles.

“As long as we have these secondhand or dilapidated cars on the road, the efforts of the Anti-Smoke Belching Unit and even the Private Emissions Testing Centers will make no sense because the problems are already out there,” said Jundy del Socorro, officer in charge of the Air Quality Management Section under the DENR Environmental Management Bureau.

But the price of modernization is steep. Drivers and operators have said that financing the jeepneys — currently pegged at between P1.6 and P2.1 million — with low government subsidy makes it difficult to afford new units.

Many jeepney operators and drivers also decry having to shoulder the blame for the pollution, saying that private cars that similarly emit pollutants are much bigger in number.

Socially just

While it has its merits, the modernization program has to be socially just, said Mylene Cayetano, head of the Environmental Pollution Studies Laboratory of the UP IESM.

“For example, if I’m driving a diesel-powered private car, my carbon footprint is much bigger than a diesel-powered jeepney that carries 20 passengers,” Cayetano said. “But in terms of exposure to polluted air, those in the jeepney are again at the losing end because they cannot afford an air-conditioned car.”

In an interview with the Inquirer last year, Dr. Maria Neira, director of public health of the World Health Organization (WHO), said the government should invest in healthy urban planning and promote a cleaner public transport system to discourage the public from using private cars that take up more space on the road.

Strengthening the mass transit system across the country can improve not only air quality and transport efficiency but also boost development and progress, said government experts and those in the academe.

The DOTr’s programs of late has focused on strengthening the transit systems across the country, with the rehabilitation and overhaul of the Metro Rail Transit (MRT) 3 line and the extension of the Light Rail Transit (LRT) 1 and 2 to the south (Cavite) and the north (Antipolo), respectively.

The agency is also currently building the MRT 7 line and the country’s first subway to connect Quezon City to Bulacan province and Pasay City.

WHO climate researcher Arthur Wyns said that while it was easy to blame people for their choices that might lead to more pollution, the lack of alternatives should be seen as the root cause.

“There needs to be infrastructure to facilitate the people’s shift (to eco-friendly transport),” he said. “If there are no safe bicycle lanes, who is going to bike? It’s a structural issue, not just an individual lifestyle problem.”

Emerging cities should also learn from the metro’s current challenges and aim for a more inclusive and sustainable development, experts said. Instead of eyeing only the improvement of PUVs, a massive urban renewal and practical alternatives are needed to curb the overreliance on private vehicles.

For both national and local governments, this requires political will and putting priority on their constituents’ rights and needs—including clean air.

“[Ensuring we have] clean air is everybody’s job, not just the government’s,” Cayetano said. “[If we don’t address the problem,] we all lose because air pollution has no boundaries. It will affect us all, rich or poor, because we are breathing the same air.”