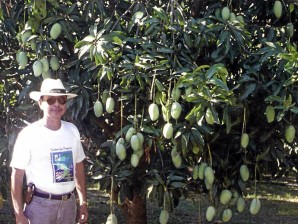

AVELINO Lomboy, the former La Union agriculturist, believes that agriculture research and technology will help boost the country’s economy. CONTRIBUTED PHOTO

AVELINO LOMBOY, the retired provincial agriculturist of La Union who is credited for propagating grapes in the province, did not have a normal childhood.

Growing up in a farm in Bauang town, he had to work for everything.

Every day, before going to school, Lomboy would feed the family’s carabao, chickens and pigs. When he got home in the afternoon, he would again tend their livestock.

On weekends, apart from looking after their farm animals, he went to the mountains to gather firewood that he would sell so he could have money for school expenses.

In high school, he and his friends would cut down growth in the mountains and plant ipil-ipil so they could pay their tuition.

He also helped his parents, who were also engaged in fishing, tended their tobacco and rice crops.

Though most of his older brothers and sisters had jobs, Lomboy, the youngest in a brood of eight, did not want to be supported by his siblings.

“I refused to bother my siblings. I wanted to prove that I could stand on my own,” Lomboy says.

At an early age, he believed that farmers could help propel the economy, and the country could benefit from agriculture.

He says the government should fund more research on crops that could adapt to global warming, develop location-specific technology and farming technologies, such as green-housing, which would increase the survival rate and productivity of crops.

Research

“All progressive countries start with research,” he says.

He hated that farmers had to work so hard for meager returns, he says. He understood the plight of farmers, who, he says, hardly make enough food for their families.

With hope and resolve, Lomboy sought to change the system and improve the lives of his fellow farmers.

“I wanted to change the agricultural landscape of the place. I wanted bare subsistence agriculture to be transformed to a higher level of farming. I wanted to introduce crops that are not traditionally grown in the area,” he says.

After graduating from Araneta University in 1966, Lomboy worked as farm manager for Chemical Industries of the Philippines (Chemphil), a Metro Manila-based company engaged in the production of industrial chemicals. However, three years into his job, he realized that his heart was in farming.

He quit Chemphil in 1969 and returned to his hometown in Bauang. He tried his hand at growing bananas, mushrooms and vegetables, but without much success.

Grape growing

In 1972, he shifted to growing grapes on the advice of a friend. Being in a tropical country, Lomboy knew that farming conditions might not support grape growing because the crop suits a temperate climate. But this obstacle only inspired him to try growing grapes, paving the way to his success.

“Grape growing in the Philippines is not a normal process—grape is not a normal product, it is not a normal crop. I was challenged. I read some literature and experimented with local varieties. I imported seeds from the United States and planted 20 vines in my backyard,” Lomboy says.

“I was on my own. I had nobody to ask about how grapes are supposed to be cultured,” he says.

After a year of experiments, Lomboy’s vines bore fruits. After two years of continuous research and tests, he discovered the key to the production of grapes.

“Grapes love long dry seasons, and the Ilocos region has long dry seasons. Where mangoes thrive, grapes will thrive,” Lomboy says.

He then sought to increase his production. He planted 40 more vines and, soon, he was tending 300 vines. He found himself renting more land as his production increased.

In 1984, he was growing grapes on a combined 25 hectares of land in Iloilo, Masbate, Nueva Ecija and La Union. Three years later, his business took off.

Lomboy says while countries that normally produce grapes harvest only once a year, he was harvesting three times a year in the late 1980s to the 1990s.

But it was not all calm waters for Lomboy.

Several foreign organizations discouraged him from growing grapes, saying these cannot be grown profitably in the Philippines.

In the 1990s, some foreign scientists met with him, and then Agriculture Secretary Senen Bacani and told them that the country should change its grape variety.

Lomboy, however, stood his ground.

“They were asking us to remove and change the existing grape varieties. I told them that it was a private enterprise and the government did not spend even a single centavo in my project. I told them to prove me wrong, to show me that their variety is better,” Lomboy says.

He also lost millions of pesos to heavy rains and typhoons, but this did not deter him since, he says, he still made money.

“My farms collapsed many times due to rain. But it is part of the equation and according to my financial statements, I’m still making money. Fortunately the cost of inputs at the time—fertilizers, pesticides and labor—was low, and the selling price of the products was high,” Lomboy says.

The late President Corazon Aquino, in 1987 and 1988, used to visit Lomboy in Bauang to thank him for creating jobs through his grape business.

Lomboy says his vineyard, during the peak of production, had seven workers and 10 indirect workers (vendors and suppliers of farming paraphernalia) a hectare.

More jobs

The business went on to produce more jobs in the late 1980s as farmers from various provinces started a similar venture.

In 1990, Lomboy’s production slowed down when the government allowed the importation of grapes.

He has since shifted to growing guapples, papayas and mangoes in his farms in La Union and Nueva Ecija, and has limited his grape cultivation.

Lomboy says he believes that farmers must engage in diversified farming by planting “cash crops” like vegetables which can be harvested after 30 to 60 days, “medium-term crops” like guapples and papayas which mature after a year, and “long-term crops” so a farmer can make money all year round.

Farmers, he says, should avoid mono-cropping. He urges them to learn from other farmers and visit their farms to share knowledge and techniques.

Continuing education for farmers would benefit the country’s agriculture, says Lomboy, who continues to give lectures to interested farmers or groups.