Tsunami, a Japanese word for harbor wave, is a series of waves commonly generated by undersea earthquakes. Many people already understand this phenomenon.

Public awareness about earthquake-generated tsunamis has been heightened by disastrous events over the past several years: the Dec. 26, 2004, 9.1-magnitude Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami (more than 220,000 deaths that affected 15 countries); the Feb. 27, 2010, 8.8-magnitude earthquake and tsunami that hit Chile (525 dead); and the March 11, 2011, 9-magnitude Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami (more than 15,000 deaths).

What is not as well-known is that tsunamis can be produced by other natural phenomena aside from an undersea earthquake.

Less commonly, tsunamis can be generated by underwater landslides, infrequently by volcanic activity and very rarely by large meteorite impact.

The 7.5-magnitude earthquake in Palu, Indonesia, on Sept. 28 was from an on-land fault, but surprised many when it triggered a tsunami with 7-meter waves.

The tsunami, believed to be due to a massive undersea landslide, killed 2,256 people.

Mindoro Oriental

The earthquake in Mindoro Oriental on Nov. 15 1994, was also suspected to have been triggered by an undersea landslide after an on-land fault (Aglubang Fault) generated a 7.1-magnitude temblor.

Tsunami affected the towns of Puerto Galera, San Teodoro, Calapan and the Island of Baco, killing more than 70.

Tsunamis associated with volcanic eruptions or activities have been recognized in the past. These are caused by eruptions commonly through the following:

1. Violent explosions from submarine volcanoes that disturb and displace the waters.

2. Voluminous pyroclastic materials flowing downslope, discharging into a body of water and causing large waves.

3. Landslides when an eruption causes slopes to move into a body of water and displace it (e.g. caldera collapses or flank failure).

The tsunami on Dec. 22 that swept the coastal communities in the Sunda Strait seems to have been caused by landslides from flank failure in the southwest slope of Anak Krakatau.

Taal Volcano

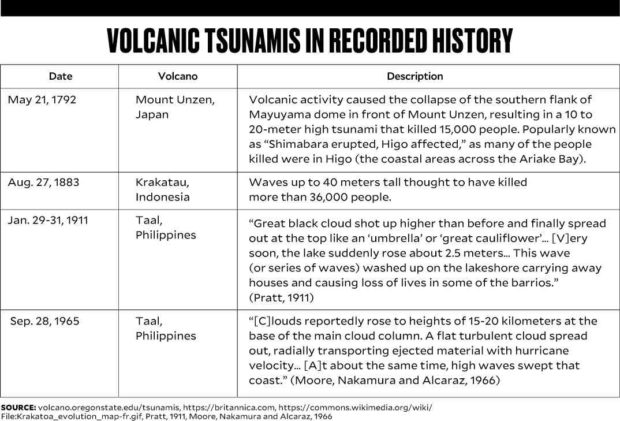

In the Philippines, many instances of large waves triggered by strong Taal eruptions, specifically in 1911 and 1965, have been recorded.

We call it seiches (disturbance of body of water in an enclosed setting in this instance Taal Lake). Using present-day terminology, it can also be called volcanic tsunami.

Eyewitness accounts of the Sept. 28. 1965, eruption describe waves that inundated coastal communities. That is why people should avoid the lakeshore and be evacuated in case Taal Volcano erupts.

Warning system

The US Pacific Tsunami Warning Center was established in 1949 following the 1946 Aleutian Island Earthquake and tsunami that resulted in 165 casualties in Hawaii.

This is now part of an international Tsunami Warning System (TWS) participated in by countries around the Pacific.

The Philippines through the years also has established a seismic and tsunami monitoring network. We now have 100 seismic monitoring stations and 29 tide gauges.

We are linked with the Pacific TWS.

A similar TWS was agreed to be set up starting 2005 for the Indian Ocean following the 2004 Indian Ocean event, with Indonesia, India and Australia spearheading tsunami warnings.

Putting up a system in each country is not an easy task, and making the monitoring networks from different countries interoperable and sustainable is a challenge.

Just when we seemed to have gained better understanding of undersea earthquake-generated tsunamis, Anak Krakatau unleashed its wrath as a reminder of this “other” infrequent yet potentially dangerous process that could generate tsunamis.

Why was there no warning in the Anak Krakatau event?

Residents of the coastal communities were caught unawares of the incoming waves. Anak Krakatau (Child of Krakatau), which grew after the calderagenic eruption that destroyed the original Krakatau in August 1883, has a resurgence of activity since June.

Part of the hazards

Indonesia may have networks for monitoring volcanoes for forecasting eruptions, but has no specific monitoring and warning for a possible tsunami event related to eruptions.

There is no early warning similar to earthquake-related tsunamis.

Volcanic tsunamis should be part of the hazards that people should be prepared for. But unlike earthquake-related tsunamis, there is no one-on-one warning relationship for an eruption and a tsunami.

People on shore should be evacuated to safer ground every time a volcano explodes or is erupting.

Raising awareness for infrequent but equally potentially devastating events is a lesson that should be remembered and learned.

Anak Krakatau, a tiny volcano island, is in the middle of Sunda Strait seemingly isolated, but the waves it generated affected surrounding coastal communities, such as those in mainland Java.

Unexpected? Probably yes, but when we analyze Krakatau’s history—tsunamis happened in 1883 when Krakatau erupted.

Old Japanese saying

Again we are reminded of the old Japanese saying, “A disaster strikes when the last one have been forgotten.”

Volcanic eruptions and the hazards they pose are not new to us, but the impact of the recent Anak Krakatau event should serve as a reminder to all.

Thorough assessment of hazards during volcanic unrest must be taken into account, using scientific studies as well as exhaustive understanding of historical and oral accounts.

We have to bear in mind that during an eruption, hazards evolve while a volcano’s morphology constantly changes. These are compounded by factors such as unstable slopes due to loose materials from pyroclastic eruptions.

Together with additional scientific studies, there must be volcanic tsunami-hazard education, awareness and preparedness measures to keep people and property safe. —CONTRIBUTED

(Editor’s Note: Renato U. Solidum Jr. is a science undersecretary and officer in charge of the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (Phivolcs). He received his Ph.D. in geology from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography-University of California.

Ma. Mylene Martinez-Villegas is chief science research specialist at the Geologic Disaster Awareness and Preparedness Division of Phivolcs. She obtained her MS Geology from Arizona State University, and Master of Development Communication and Doctor of Communication from the University of the Philippines-Open University.)