Indigenous peoples secure voice in climate talks

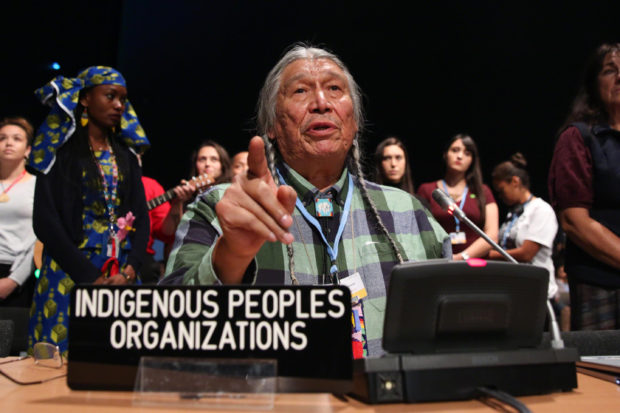

Francois Paulette, who represents the indigenous peoples at the 24th Conference of the Parties of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change in Katowice, Poland, says their indigenous knowledge can complement the science in finding solutions for climate change. PHOTO by IISD/ENB | Kiara Worth

KATOWICE, Poland — Indigenous peoples across the world have secured their voice in the climate conversation, after representatives from nearly 200 countries reached an agreement for a platform allowing more participation of local and indigenous communities in addressing the climate crisis.

The adoption of the Local Communities and Indigenous Peoples Platform during the UN climate talks in this southern Polish city was a welcome development among delegates who had been at loggerheads over other issues, particularly concerning the implementing guidelines of the landmark Paris Agreement.

Francois Paulette, a representative of the indigenous peoples, said that its adoption was a positive move, as their lands and waters were “rapidly being destroyed” in front of their very eyes.

“Our traditional knowledge is infinite and we have lived with Mother Earth very closely for thousands and thousands of years without destroying it,” the respected Denesuline elder from Canada told the plenary.

“Western science has its limits and this is why the indigenous peoples are here to help and assist you in what is happening in the destruction and desecration of Mother Earth.”

Article continues after this advertisementHis remarks were followed by a Maori song performed by indigenous peoples from New Zealand about protecting and caring for the planet, which was met by applause.

Article continues after this advertisementThe platform will strengthen the knowledge, technologies, practices and efforts of local and indigenous communities in addressing and responding to climate change. It would also facilitate the exchange of experiences and best practices and lessons on mitigation and adaptation.

Under the platform, a facilitative working group will be established, consisting of representatives from the five UN regional groups — one from a small island developing nation, one from a least developed country and seven from indigenous peoples organizations from the seven UN indigenous sociocultural regions.

According to the United Nations, indigenous peoples make up to five percent of the world’s population, but they care for around 80 percent of the world’s remaining biodiversity.

Despite their huge contribution in protecting forests and other natural resources, they bear the brunt of climate change impacts, said Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, UN special rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples.

“They feel the direct effects of climate change and yet they did not contribute anything to this problem,” she said in an interview. “So it is really important for them to have a voice and come here to influence the processes in the convention, as well as in the national level.”

Corpuz, an Filipino indigenous activist with Kankana-ey Igorot roots, also underscored the importance of climate finance to support indigenous communities that are disproportionately affected by global warming.

She said, for instance, that if indigenous communities want to protect their forests, there should be resources to support forest guards in their area.

But for Corpuz, the challenge also lies on their capacity to assert themselves, amid threats to their lives, rights and cultures.

Brazil’s incoming president Jair Bolsonaro, for instance, had threatened the Amazon and its native communities after he expressed intention to open the indigenous land for mining and loosen environmental regulations that protect the world’s largest tropical rainforest. /ee