PHOTO BY CLIFFORD NUÑEZ

RIZAL, Occidental Mindoro — Kalibasib, the lone surviving Philippine tamaraw (Bubalus mindorensis) bred in captivity, is aging.

His left eye has turned cloudy, a condition that veterinarians at first thought was caused by cataract.

Recently, a wildlife specialist who saw Kalibasib said the cloudiness was due to a scratch in the eye. The animal still reacts to light, he said, and is thus not blind. Not just yet.

Retiring

At 19, Kalibasib is already old (the average life span of the rare buffalos is up to 20 to 25 years), and it might take a while for his eye to heal, said Teresita David, coordinator for the Tamaraw Conservation Project (TCP), a program under the Department of Environment and Natural Resources.

“We are worried, though, that he might have to retire soon [because of old age],” David said.

Kalibasib had its third quarterly health checkup in October, incidentally the month dedicated to the conservation and protection of tamaraws in Mindoro. The species is endemic to the island and listed as critically endangered.

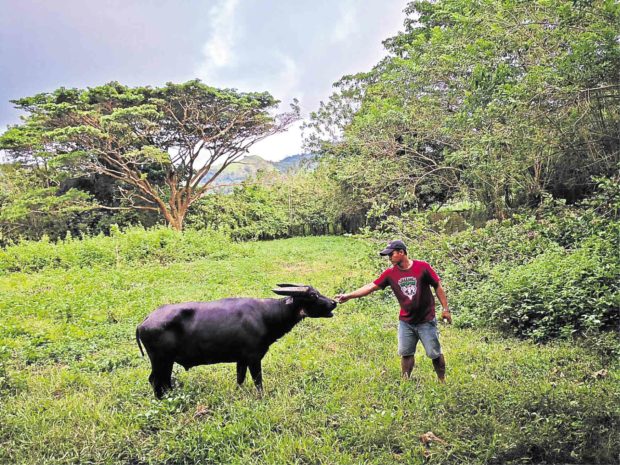

MINDORO’S PRIDE Only experienced tamaraw watchmen, like Onie Ordo, can get close to Kalibasib inside the pen of the dwarf water buffalo, which is endemic to Mindoro island. Photo below shows a herd of critically endangered tamaraws roaming on Mt. Iglit-Baco. PHOTO BY CLIFFORD NUÑEZ

PHOTO BY GREGG YAN

Star attraction

Kalibasib is about a meter tall and weighs just as much as a “2-year-old carabao,” David said. Generally considered in good health, he is the gene pool’s star attraction.

Last year, many of the 95,846 tourists who visited the more urban neighboring town of San Jose did not miss the chance to see the tamaraw up close.

The trip to the 280-hectare facility at Barangay Manoot in Rizal town requires a little trekking amid the picturesque view of the mountains and crossing a footbridge hanging above a shallow river.

Kalibasib stands for “Kalikasan Bagong Sibol” (nature newly sprung), a name fitting for the only dwarf buffalo produced and has survived this long at the breeding center.

Another captive-bred tamaraw did not last a year.

Kalibasib’s mother, Mimi, was among the 20 adult tamaraws taken from the wild when the Tamaraw Gene Pool Farm was opened in 1980. But the offspring were stillborn and the adults eventually died from pests and diseases, the most common of which were liver fluke and pneumonia.

“Aside from old age, they are not used to being confined. They are roaming animals in their natural habitat,” David said. Kalibasib roams alone in the 4,028-square-meter fenced range.

Failure

“To many, [captive breeding] may have been a failure,” David said. “But on a brighter side, it has bred two [animals] and with Kali (Kalibasib) surviving 19 years. Considering the [lack of] technology [back then], let’s give it to the program,” she added.

Kalibasib has grown accustomed to people, gamely reaching with its mouth a banana fed through the fence by visitors. This is in stark contrast to tamaraw behavior in the wild that is generally territorial and elusive, said Onie Ordo, 35, a tamaraw watchman for eight years now.

On Mt. Iglit-Baco, a protected area that is home to the biggest tamaraw population (523), the closest people can get is at 25 meters. They view tamaraws through binoculars.

Threats

“I talk to him sometimes and ask him if he’s hungry,” Ordo said of Kalibasib. Sometimes, he said, he pities the tamaraw when it jumps at the sight of a passing carabao, as if it wants to join the herd.

“But we couldn’t let him out,” Ordo said. “He’s not used to their ways in the wild and he might just get killed.”

Poaching and hunting by the indigenous Mangyan and lowlanders remain a threat to tamaraws, though years of conservation efforts by government and nongovernment groups pay off with more recent sightings of tamaraws.

David said 10 to 15 head were seen on Mt. Aruyan and 60 to 70 more at Amnay Watershed.

The government is planning several more expeditions next year to explore possible habitats. But the bigger challenge is balancing wildlife protection and respecting indigenous peoples’ rights.

“The Mangyan tell us they used to live with the tamaraws until civilization drove them up to the mountains. They believe that if the tamaraws become extinct, they would, too. The Mangyan and the tamaraws coexist,” David said.

Different

“We encourage Filipinos to go see Kali. It’s not like just seeing [its picture] from a book. [Tamaraws] are a part of our being Filipinos,” she said.

After the captive breeding program was scrapped, the government converted the gene pool into a biodiversity rescue and conservation center where a rescued crocodile, named Oca, and two Philippine pond turtles are being taken care of.

The TCP, in partnership with the Philippine Carabao Center and the Department of Science and Technology, plans to put up a laboratory on site and a tamaraw sperm bank.

David said the plan was to collect sperm from Kalibasib and have it preserved. For what specific purpose is still unclear, she said.

What’s certain is they have to do it sooner before time runs out on the aging tamaraw.

IN THE KNOW

The tamaraw (Bubalus mindorensis) is one of the Philippines’ critically endangered species. It resembles the carabao, only it is smaller and its horns are shorter, which grow upward in a “V” form. Its dense hair covering is dark brown to grayish black and is thicker and darker than the carabao’s.

Also called the dwarf water buffalo because it grows only about a meter tall, it is the largest native land mammal in the Philippines and it can only be found in Mindoro.

The critically endangered species is solitary in nature, except during breeding when a bull and a cow are usually seen together. A tamaraw cow usually bears only one calf once every two years and the young is separated from the mother when it is between 2 and 4 years old.

Ferocious and aggressive, the animal has a very keen sense of smell and can detect an attacker even a mile away.

According to the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), the tamaraw population was estimated to be 10,000 in the early 1900s but because of a rinderpest outbreak in the 1930s, the figure declined drastically.

The biggest number was recorded at Mt. Iglit-Baco National Park in Occidental Mindoro. The 2018 count held there in April recorded 523.

Seventy other tamaraws were found at Upper Amnay Watershed in Sablayan, while others were reported to be on Mt. Aruyan, Mt. Bongabong, Mt. Calavite and Mt. Halcon.

In early October, up to 30 were seen grazing again on Mt. Gimparay at Naujan town in Oriental Mindoro. The last published record of tamaraw sighting in the province was in Catuiran River in 1887, or 131 years ago, according to the Mindoro Biodiversity Conservation Foundation Inc.

Tamaraws are threatened mainly due to habitat destruction and hunting. This has forced the animal to move further inland, into denser vegetation, making them harder to monitor. While they usually forage on grass, they are now thriving on different forms of vegetation in secondary forests.

Presidential Proclamation No. 273 of 2002 declares October of every year a special month for the Conservation and Protection of the Tamaraw in Mindoro.

Sources: DENR, National Museum, Inquirer Archives