Command responsibility? Chiefs of erring cops go scot-free

(Last of two parts)

Much blood was spilled on Aug. 15, 2017, apparently the deadliest day in President Rodrigo Duterte’s brutal campaign against drugs.

In the province of Bulacan alone, 32 people were killed in simultaneous police raids. And the President took the numbers as a boost to his administration’s central policy: “Those who died in Bulacan, 32, in a massive raid, that’s good,” he had said. “If we can kill another 32 every day, then maybe we can reduce what ails this country.”

More bloodletting followed. In three days, at least 81 people were gunned down in northern Manila and Bulacan. The dead included Kian delos Santos, 17; Carl Arnaiz, 19; and Reynaldo de Guzman, 14—all allegedly killed by Caloocan policemen.

Most of the cops tagged in the teenagers’ deaths were rookies, or those with the rank of police officer 1 (PO1).

Also relieved for command responsibility were their superiors—the chief of the Northern Police District, Director Roberto Fajardo; the Caloocan police chief, Senior Supt. Chito Bersaluna; the Santa Quiteria precinct commander, Chief Insp. Amor Cerillo; and the Maypajo precinct commander, Chief Insp. Fortunato Ecle.

But while these officials were also involved in the fatal operations by commanding the intelligence-gathering, coordination and execution, they were relieved only to clear the way for the investigation of their subordinates.

Rarely held liable

This shows the deeply hierarchical culture in the Philippine National Police, in which ranking officials from inspector to director are rarely held liable for the same charges that a PO1 might face.

That much was clear in a May 17, 2017, internal memo by now PNP Director General Oscar Albayalde taking to task a superior officer for “failing to act or prevent his subordinates from transgressing the law.”

Ultimately, however, superiors are not held accountable for their subordinates’ offenses.

That their ranks often insulate superiors from more serious punitive measures is at odds with the PNP’s drive for internal cleansing.

The chief of the National Capital Region Police Office (NCRPO), Director Guillermo Eleazar, said officials played a crucial role in ensuring accountability within their ranks.

“We often blame PO1s, but the truth is [the operations] are the responsibility of their supervisors. PO1s would hesitate to err if he knows his commander won’t stand for such,” Eleazar said in an interview.

Carlos Conde of Human Rights Watch echoed that view: “We should study closely the offenses PO1s commit because it is very likely that they were just following orders. Being rookies, [they] are forced to do their commanders’ bidding.”

To better understand how accountability works in the PNP, the Inquirer traced at least 35 ranking officials in Metro Manila relieved for command responsibility since 2016.

Most of the time, a ranking official whose command showed a pattern of misconduct among his subordinates was merely relieved and put on floating status, not charged in court.

Bartolome, Bersaluna

Of all the police chiefs in Metro Manila, no one has gotten around more than Senior Supt. Dionisio Bartolome. He has led the police forces in the cities of Makati, Pasay and Muntinlupa since 2016.

Within months, he would be stripped of his command, twice for allegations of grave extortion. It was only until the NCRPO raided his drug unit in Muntinlupa for alleged kidnap-extortion that he was ultimately put on indefinite floating status.

“We can’t say [with] 100-percent certainty that these things happened because of him,” Eleazar said. “Maybe it’s a coincidence. But it’s still a legitimate concern because regardless of wherever you placed him, his commands were marred by allegations like that.”

Bersaluna, for his part, was removed in the wake of the nationwide outrage over Kian delos Santos’ death. His yearlong tenure as Caloocan police chief marked the city as a killing field in the war on drugs, and the sharp censure over the teenagers’ deaths was thought to be a watershed in the brutal campaign.

But the killings continued under Senior Supt. Jemar Modequillo, in the hands of motorcycle-riding gunmen. Modequillo was later relieved for the high number of unsolved shootings in Caloocan; he was not reassigned to a new post for over eight months.

In February—six months after Kian’s death—Bersaluna became San Juan police chief. In May, he was promoted as provincial police director of Bulacan, his tenure in Caloocan all but forgotten.

The killings in Bulacan have risen sharply since then.

Sacking en masse

Another curious trend was that the NCRPO often sacked policemen en masse even if only a handful were actually involved in offenses. Illustrative, for example, was the abrupt relief of the then NCRPO chief, Director Joel Pagdilao, and nearly every member of the regional and the Quezon City drug units in July 2016.

In the same month, the PNP launched its “Oplan Double Barrel,” which is composed of “Upper Barrel” (police-led operations on high-value targets) and “Lower Barrel” (more commonly known as “Oplan Tokhang,” the knock-and-plead approach to the antidrug campaign).

Pagdilao’s replacement, Albayalde, became Double Barrel’s staunchest advocate.

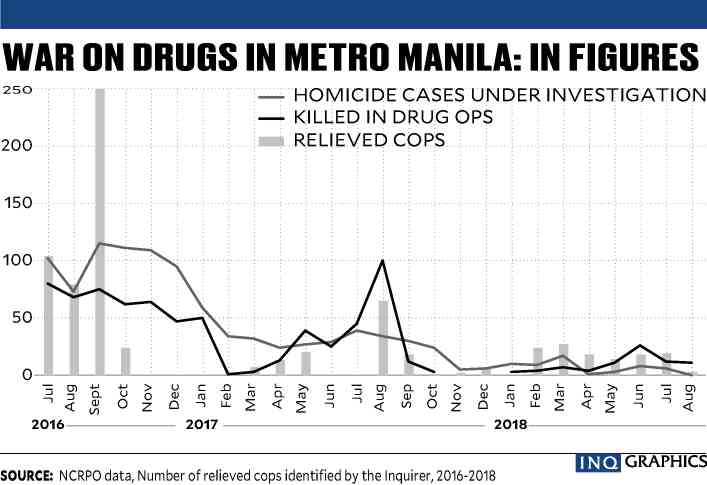

The graph shows the correlation among the number of relieved policemen, drug personalities killed in drug operations, and homicide cases under investigation (HCUIs). Data from news reports and the NCRPO show that temporarily relieving erring cops in the course of the two-year war on drugs did not necessarily lead to a decline in the number of people killed in drug operations and HCUIs.

In 2016, 457 cops across Metro Manila were relieved for various offenses, 396 suspected drug personalities were killed in police drug operations and 605 deaths were recorded as HCUIs. In 2017, 133 policemen were relieved, 291 killed in drug operations and 388 tagged HCUIs.

As of August, 123 cops had been relieved of their posts, 78 killed in drug operations, and 54 deaths recorded as HCUIs.

But there’s a glaring gap in the NCRPO’s record of drug-related deaths in August 2017. Across Metro Manila, the NCRPO recorded only 100 deaths from police operations and 34 HCUIs, despite a record of 81 deaths in a single day from “one time, big time” operations.

Spike in arrests

The number of drug war deaths has been considerably declining since 2017, and the trend has shifted to massive arrests of suspected drug personalities.

About 43,000 were arrested in Metro Manila for alleged violations of the Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act. This year’s records show that drug-related arrests have reached more than 2,000 monthly.

Conde said that for a “genuine drug war” to work, arresting suspects and charging them in court should have been the government’s model. “But arresting them has little shock effect, has little political value for Duterte and his people who have been using the drug war … to score political points, to terrify people into submission, etc.,” he said.

Some of the cases against scalawag cops, including those on drug-related charges, have been dismissed by the courts and the Office of the Ombudsman, often because of lack of evidence.

Conde pointed out that the President had time and again said he would not allow policemen to be brought to court for doing their job in the war on drugs.