Ibaloy burials ensure the dead at peace on Mt. Pulag

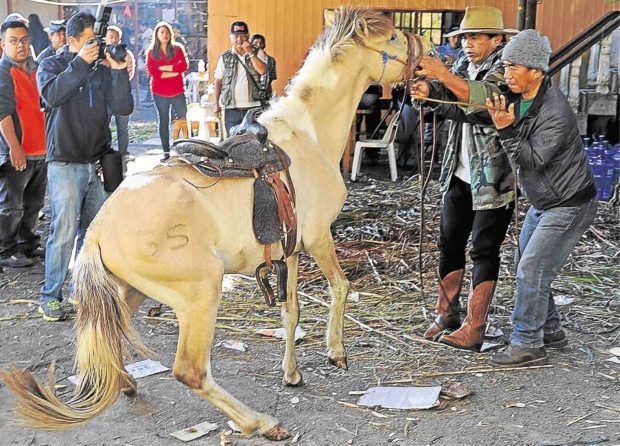

RIDE TO AFTERLIFE A horse is sacrificed during the community wake for former Benguet Gov. Raul Molintas. The Ibaloy believe that the horse will take the spirit of the departed to Mt. Pulag to join their ancestors. —PHOTOS BY EV ESPIRITU

BAGUIO CITY — With the swing of an ax, a horse was sacrificed at dawn on March 12 so it could “carry” the soul of a former Benguet provincial governor to Mt. Pulag, in a rare burial ceremony still practiced by the Ibaloy.

Raul Molintas, fondly called “Rocky” by family and friends, passed away in February in California.

A labor lawyer, he served as governor from 1995 to 2004.

He was recognized as “baknang” or “kadangyan,” Cordillera terms for the elite or highly regarded members of the Ibaloy community.

It required Molintas’ remains to be flown back here for the communal wake known as “aramag.”

Article continues after this advertisementFor a baknang, the aramag took nine days and required a daily sacrifice of animals in pairs, including male and female horses.

Article continues after this advertisementRituals

Like many Cordillera communities, the Ibaloy have preserved a belief system that highly reveres ancestors and is still embraced by younger generations who are taught by the elders that the spirits of the departed continue to influence the lives of their descendants.

DEATH BLANKET Ibaloy death rituals require the selection of the right blanket to wrap around the dead.

Io Jularbal, head of the indigenous cultures program of the University of the Philippines Baguio, said aramag and similar practices are “transitional” rituals and failure to perform these could leave the “kedaring” (spirit) adrift and unable to find peace.

Ibaloy burials are also community affairs, not intimate gatherings to which most Filipinos are accustomed.

Elders and the “mambunong” (native priest or ritual leader) oversee the rituals on behalf of the grieving families.

Instead of the spouse or immediate family members of the deceased, young members of the community are called to prepare, wash and clothe the remains.

That’s because the widow or widower is barred from viewing the body so as not to be “dragged down with the dead” by an illness or an accident.

They must choose the right “pinagpagan”—the blanket that is wrapped around the body as it is prepared for entombment — so the dead would not manifest his or her “discomfort” through the descendants’ dreams or bring tragedy or sickness to a family member, Jularbal said.

Keeping the dead in tranquility is the goal of these rituals, said Sonia Celino, Molintas’ aunt who took part in the rite in March.

Sacrificial animals

During the wake, a pair of male and female animals is butchered as an offering to the departed.

Typically, families sacrifice black pigs. But the more influential the family, the bigger the sacrificial animals, such as cattle or carabao. In Molintas’ case, it was a pair of horses.

The animals are cooked and served to guests, while a portion of the meal is reserved for the dead to be taken back to the afterlife.

The rituals require male and female animals, the pairing symbolizing reproduction, so the soul can thrive and dwell comfortably in the spirit world.

On the third day of the wake, visitors offer the “upu” (sometimes spelled “ofo”). Similar to a “padala,” or a gift sent by courier, it can be in the form of money donations or animal sacrifices which the departed can take to the ancestors of other Ibaloy families.

‘Quiet place’

The butchered horses are meant to take Molintas to Mt. Pulag, which to the living is Luzon’s highest peak straddling the provinces of Benguet, Ifugao and Nueva Vizcaya.

For the Ibaloy, Mt. Pulag is where the spirits rejoin their forebears. Celino described it as “a quiet place, a place of adoration, a place of calmness.”

A day after the burial, another rite called “sabusab” is held to help restore the grieving family and the community’s sense of well-being.

Everyone is asked to join in order to receive the spirits’ blessings as they move on with their lives. —Reports from EV Espiritu and Valerie Damian