Doing time in ‘Hell’: Life in Sierra Leone’s rundown prisons

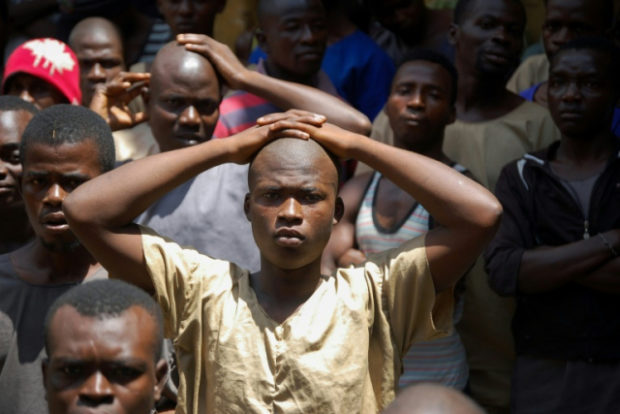

Stand and be counted: roll call at Kemena prison. The jail was built in 1826 during the British empire — it accommodates four times its regulation capacity. Image: AFP/Saidu Bah

A shaft of light penetrates the foul air through a fist-sized vent.

It reveals naked, sweating bodies packed side-by-side like sardines, lying in darkness on a greasy concrete floor.

The stench of urine and excreta from a brimming plastic bucket — just one for a cell containing perhaps 20 people — claws at the throat.

This was the scene at the Bo Correctional Facility in southern Sierra Leone.

It was one of eight prisons that this reporter visited last week to assess the state of penitentiaries that independent voices say are a national scandal.

The tableau that emerged was tropical Dickens — crammed, poorly-lit cells, whose inmates said they were suffering with disease, rotten food, cockroaches and super-sized bedbugs, and a climate of jungle-like violence.

“I was caught with two parcels of marijuana. I have spent three years on remand — it’s like living in Hell,” one inmate said.

“Lack of space is so bad that people have to take turns” to lie down, said another, who like many other inmates asked not to be named, explaining they feared reprisals by guards.

“Blankets and mats are a luxury in our cell. Even some of the food we eat has an offensive smell,” added another prisoner.

A convict with crutches in a jail at Kenema, the West African country’s third largest city, said “violence among inmates for food, water and space is common.”

“This is a jungle — it’s survival of the fittest,” he declared.

In 2016, Sierra Leone’s Human Rights Commission denounced the squalor and lack of rehabilitative or educational programs in the country’s prisons as “inhumane.”

Walter-Neba Chenwi, a specialist in the rule of law at the UN Development Programme (UNDP), which has a project to improve Sierra Leone’s jails, said the conditions “fall far below international standards of human rights.”

“We treat people in detention as if they don’t exist,” said Ahmed Jalloh, an activist with a local watchdog group, Prison Watch.

Packed

“Out of 4,525 inmates across Sierra Leone jails, we have an excess of 2,659 people in detention, forced into overcrowded cell blocks,” the director of human resources at the Sierra Leone Correctional Services, Dennis Herman, said.

Kenema prison, a stone-walled jail built in 1826 during British colonial rule, has a regulation capacity of 75 inmates, but accommodates around 300, prison director Lamin Sesay said.

At Bo penitentiary, intended for 80 prisoners but housing 300, guard Mohamed Opinto Jimmy said between 15 and 20 people were being packed into cells that, according to regulations, should have a maximum of four.

Disease

Prison workers also point to disease which is rife and poor access to healthcare.

In Bo, there is a single healthcare worker for 300 inmates, many of whom suffer from chronic illnesses such as TB, AIDS and malaria.

“Some inmates are too weak from anemia to walk around the cell blocks — they wedge themselves into little corners for food, water and space,” the healthcare worker said.

The skin disease scabies is commonplace, but inmates often can only shower once a week because water is rationed.

Prisoners at Bo are tasked with trekking kilometers (miles) to polluted streams or hand-dug wells to fill jerricans and haul them back to the jail.

“Given the risk of escape, we usually assign many guards to escort inmates,” said a prison guard, Jimmy.

“But inmates are usually stigmatized by locals seeing detainees walking the streets in prison outfits.”

Reform

Still within this grim picture, chinks of light are starting to emerge.

Sierra Leone’s Department of Justice has just completed a “From Prison to Corrections” program, supported by UNDP and the United States, to train 30 prisoner officers and promote higher welfare standards.

And UNDP is doing construction and rehabilitation work, mainly in water and sanitation, in eight out of the country’s 19 jails.

But appeals court Judge Nicholas Browne-Marke told AFP that help was also badly needed for Sierra Leone’s under-funded, chronically-clogged judicial system.

More than 85 percent of prisoners are aged between 15 and 35.

Many of the young inmates are being held for petty crimes, and spend long periods in prison on remand or during their trial, and this causes congestion in jails, he said.

“The majority of the inmates are in jail for loitering, snatching a phone, drugs or quarrels,” Browne-Marke told AFP.

“We are trying to decongest the facilities by expediting trials. A mobile application for pending cases has been developed for all judges and magistrates to encourage a speedy trial and case conclusion.” CC

RELATED STORIES:

Congestion eases, but jails still crowded to 5 times ideal capacity