Japan eyes joint custody for divorced parents

TOKYO — The Japanese government is considering introducing a system in which divorced parents can have joint custody of their children, by reviewing the current system that grants only one of them such authority, it has been learned.

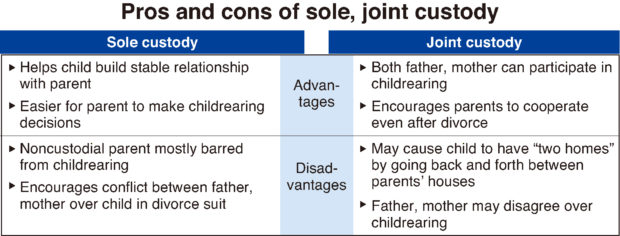

Under an envisaged system, custody rights will remain for both father and mother after a divorce. Thus, both parents will continue to be jointly responsible for raising their children. By encouraging interaction with children and divorced parents through more frequent visitation, the government aims to create an environment to facilitate the balanced upbringing of children.

The Justice Ministry is expected to consult with the Legislative Council, an advisory panel to the justice minister, as early as 2019, regarding a revision on the Civil Code to review the existing custody system, according to sources.

The Civil Code, which was enacted in 1896, strongly reflects the traditional structure of Japanese families. Some experts, therefore, have pointed out that custody has been misunderstood as a right to control children and could lead to child abuse in some cases.

The revised Civil Code, which went into effect in 2012, stipulates that a person who exercises custody holds the authority “for the interests of their children.” From this viewpoint, the government plans to start revising the law, the sources said.

Article continues after this advertisementArticle 819 of the Civil Code stipulates that custody after divorce shall be possessed by one parent. This removes from the family register the official relationship between a parent without custody and their child or children.

Article continues after this advertisementA parent who has custody holds the right and duty to educate their children and administer their children’s property, but a parent without custody is rarely involved in raising his or her offspring, and is also tightly restricted from seeing them.

On the other hand, in European countries and the United States, it is common for divorced parents to have joint custody. Thus, both father and mother jointly raise their children even after a divorce because it is widely understood that the involvement of both parents is necessary for the healthy development of children.

Regarding a planned revision of the Civil Code that will give priority to the interests of children, the government is mulling expanding the scope of the “special adoption” system, under which adoptive parents are recorded as the official parents on the family register, according to the sources.

In June, Justice Minister Yoko Kamikawa asked the Legislative Council to review the system.

To increase opportunities for children who are unable to live with their parents because of child abuse or economic circumstances to be raised in a stable family environment, there have been a number of proposals, including raising the age of children subject to the “special adoption” system to those under 12, or under 15, the sources said.

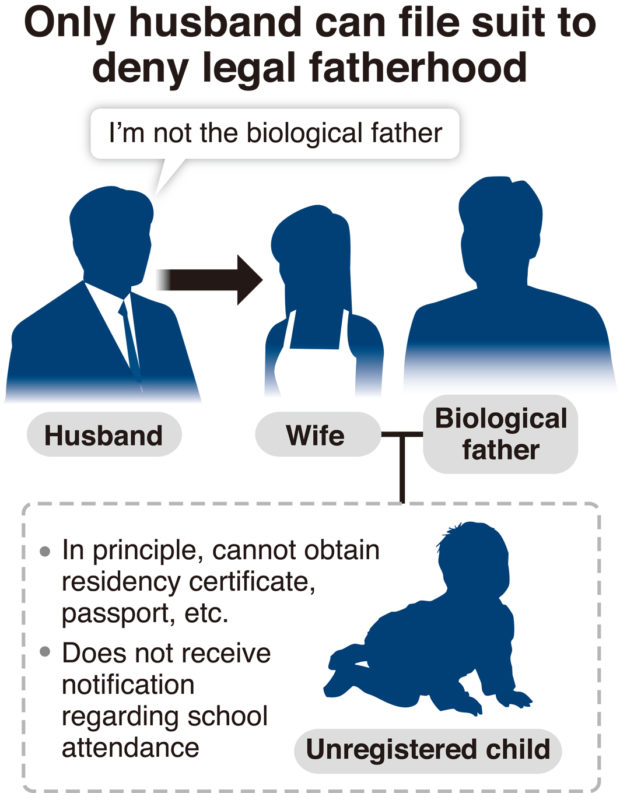

Currently, in principle, children under 6 are eligible under the system. The issue of children who are not recorded on their family register as a result of a parent not submitting a birth registration stems from the rule of “the presumption of a child in wedlock.” The rule stipulates that children born within 300 days after a divorce should be regarded as the husband’s responsibility.

Currently, only a husband, or former husband, can lodge a suit to rebut the presumption of a child in wedlock. The government is considering revising the Civil Code to allow also a mother and her offspring to have the denial-of-legitimacy right, the sources said.