Meet the lipstick brigade behind bars

KEEPING A RECORD: Sherryna Lorenzo

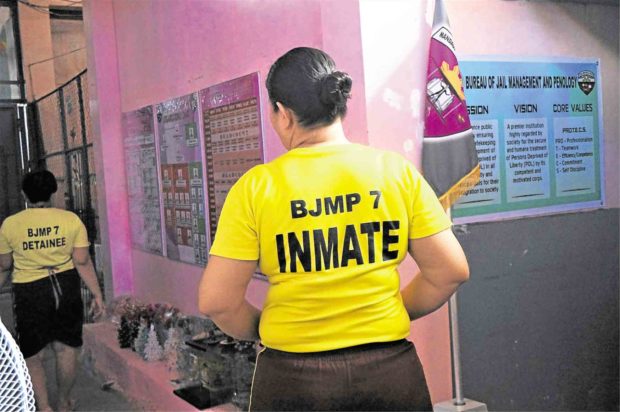

For the past 12 years, Sherryna Lorenzo has worn the same yellow uniform with the word “inmate” printed on its back. It was a generic identity the 47-year-old mother of five was forced to carry when she was convicted of illegal recruitment in 2005.

She now shares space with 181 other detainees at the Mandaue City Jail Female Dormitory in Cebu province in Central Visayas.

But Lorenzo starts and ends her day differently from her peers. A member of her dorm’s “lipstick brigade,” she puts on colorful lipstick as she leads her fellow detainees in their daily tasks.

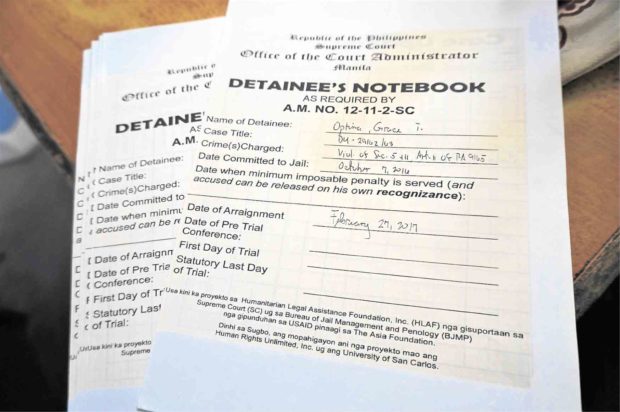

As part of the brigade, she checks on her dorm mates’ trial schedules and follows up their status in courts. It’s a responsibility that has given her a sense of purpose she never thought she’d find behind bars.

Lorenzo is one of 12 paralegal aides in the local jail who were trained to render legal assistance to the inmates.

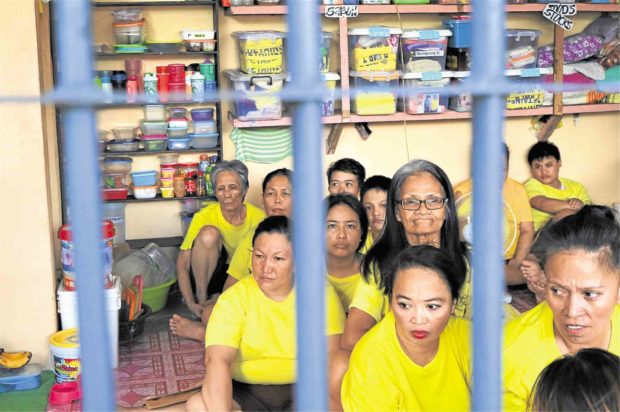

CONGESTED Delayed trials lead to the already overflowing capacity of the Mandaue City jail’s female dormitory.

“Before I was detained, I thought I already knew everything there was to learn about our legal processes. When we became paralegal aides, I realized there was so much more to learn—for ourselves and for others,” Lorenzo said.

Mandaue City Jail is one of the most congested female dormitories in the Philippines, with a congestion rate of 883 percent, versus the national congestion rate of 555 percent. Inmates occupy much less than the 4.7 square meters minimum cell area prescribed per head. With that standard, the local jail can hold only 19 inmates.

For human rights advocates and jail officials, this manifests that prisons are a last priority in the country.

“We’re depending on the national budget, and of course, we’re the least priority of the national government because we’re only incurring expenses without expected returns,” said Jail Senior Insp. Stephanny Salazar, Mandaue City Jail warden of the Bureau of Jail Management and Penology (BJMP).

The jail congestion is worsened by the frequent postponement of hearings because of the lack of time and other material factors in local courts. Women, whose main offenses are usually low-level property or drug-related crimes, often find themselves trapped in years of incarceration in these crowded cells.

It was within this context that Lorenzo realized the importance of access to legal aid inside the jail. When the paralegal training was introduced in Mandaue in 2015, she immediately volunteered.

GENERIC IDENTITY Inmates wear the prescribed yellow shirt inside jail.

“Initially, I found it difficult to accept that I would spend my life in prison. But when we were trained to become paralegals, I realized there was a purpose for my being in jail. And that was to help others obtain their freedom,” she said.

Legal first aid

On a Thursday morning, the inmates of Cebu City Jail Female Dormitory found themselves gathered in a circle singing “If You’re Not Here” by the ’70s boy band Menudo.

It was their farewell song to Renefe Baliuag, who served as the mother they thought they never needed behind bars. She was being transferred to the Correctional Institute for Women in Mandaluyong to serve her life sentence for human trafficking.

Just like in Mandaue, the Cebu City Jail is congested, with more than 600 inmates occupying space meant for only 60.

Legal assistance could certainly help those whose cases were overlooked and in the process decongest the jail.

Jail, said Baliuag, 55, has brought out the goodness in her. She could be a decent human being after all, she added.

Like Lorenzo, Baliuag and 24 others in the female dorm have become beneficiaries of the paralegal program initiated by Humanitarian Legal Assistance Foundation (HLAF), a local rights group, in partnership with the BJMP.

“I’m happy to have served as a paralegal aide because I got the chance to help my dorm mates. When I enter the Correctional Institute, I will proudly bring my diploma from the paralegal program and share my knowledge with the inmates there,” Baliuag said. “I was given a life sentence, and I thought there was no more hope for me. But the paralegal program taught me that I still have a second chance,” she said.

The paralegal manual of HLAF defines the primary responsibility of paralegals, who are volunteer inmates, as bringing the legal concerns of other inmates to jail officials.

The paralegals undergo a series of training based on four modules: pillars of the criminal justice system, rights of the accused, criminal procedures and basic criminal law.

Cathy Alvarez, program coordinator of the International Drug Policy, had seen firsthand what it meant to become a woman deprived of liberty.

An alternative lawyer, she initiated the implementation of the paralegal program in the cities of Mandaue, Cebu and Lapu-Lapu in 2014.

By providing a “mini law school” inside the jail, she used her educational advantage to connect with the inmates and give them a new sense of dignity by empowering them so they could empower others.

“They must be willing and able to help their fellow detainees. Because it’s supposed to be a voluntary (job) and they should be paralegals not for their cases only. They must also represent their cells. It’s like having a legal first aid,” Alvarez said.

Paralegal aides keep Detainee’s Notebooks to record the status of their fellow inmates’ cases.

In the Philippines, there are more than 140,000 detainees in local jails in its 17 regions. They are the so-called “untried prisoners,” said alternative lawyer Rommel Abitria, who is also executive director of HLAF.

Abitria believes that at the core of alternative lawyering is an enabling environment that allows a vulnerable group to access, use and share information they can meaningfully apply in their everyday lives.

“A paralegal officer inside a congested jail or a public attorney handling 20-40 cases won’t be able to monitor everyone’s legal needs in a day,” Abitria said.

“But if we provide the inmates with basic knowledge of the law and their rights, they will know how to give their fellow inmates a chance at freedom. It would be easier to point out who among their peers would need legal assistance the most,” he added.

This story was produced under the 2017 Southeast Asian Press Alliance’s Regional Reporting Fellowship.