Low oxygen levels, coral bleaching getting worse in oceans

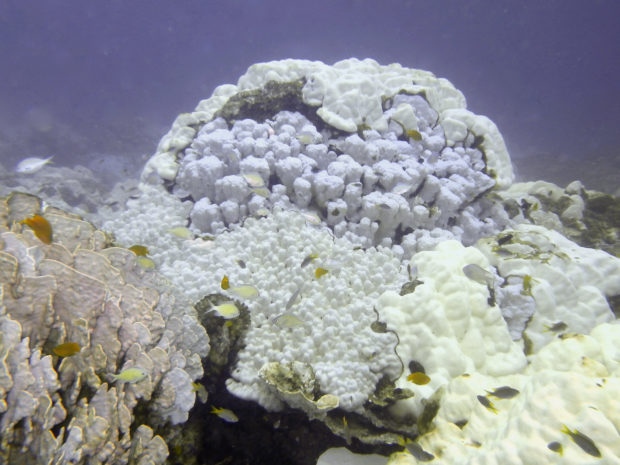

This July 2010 photo provided by NOAA shows bleached corals at Ko Racha Yai, Thailand. A study released on Thursday, Jan. 4, 2018 finds that severe bleaching outbreaks are hitting coral reefs four times more often they used to a few decades earlier. (Mark Eakin/NOAA via AP)

WASHINGTON — Global warming is making the world’s oceans sicker, depleting them of oxygen and harming delicate coral reefs more often, two studies show.

The lower oxygen levels are making marine life far more vulnerable, the researchers said. Oxygen is crucial for nearly all life in the oceans, except for a few microbes.

“If you can’t breathe, nothing else matters. That pretty much describes it,” said study lead author Denise Breitburg, a marine ecologist at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center. “As seas are losing oxygen, those areas are no longer habitable by many organisms.”

She was on a team of scientists, convened by the United Nations, who reported that the drop in oxygen levels is getting worse, choking large areas, and is more of a complex problem than previously thought. A second study finds that severe bleaching caused by warmer waters is hitting once-colorful coral reefs four times more often than they used to a few decades ago. Both studies are in Thursday’s edition of the journal Science .

When put all together, there are more than 12 million square miles (32 million square kilometers) of ocean with low oxygen levels at a depth of several hundred feet (200 meters), according to the scientists with the Global Ocean Oxygen Network. That amounts to an area bigger than the continents of Africa or North America, an increase of about 16 percent since 1950. Their report is the most comprehensive look at oxygen deprivation in the world’s seas.

Article continues after this advertisement“The low oxygen problem is the biggest unknown climate change consequence out there,” said Lisa Levin, a study co-author and professor of biological oceanography at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

Article continues after this advertisementLevin said researchers have seen coastal “dead zones” from fertilizer pollution from farms before, as well as areas of low oxygen in open ocean blamed on warmer waters, but this study shows how the two problems are interconnected with common causes and potential solutions.

“Just off Southern California, we’ve lost 20 to 30 percent of our oxygen off the outer shelf,” Levin said. “That’s a huge loss.”

Some low oxygen levels in the world’s ocean are natural, but not this much, Breitburg said. A combination of changes in winds and currents — likely from climate change — is leaving oxygen on the surface, and not bringing it down lower as usual. On top of that, warmer water simply doesn’t hold as much oxygen and less oxygen dissolves and gets into the water, she said.

In this 2010 photo provided by the Smithsonian Institution, corals and crabs lie dead from low oxygen in Bocas del Toro, Panama. A study released on Thursday, Jan. 4, 2018 finds that oxygen levels dropping in the world’s oceans, choking large areas, is worsening and more of a complex problem than previously thought. (Arcadio Castillo/Smithsonian via AP)

“Oxygen loss is a real and significant problem in the oceans,” said University of Georgia marine scientist Samantha Joye, who wasn’t part of the study but praised it. Levels of ocean oxygen are “changing potentially faster than higher organisms can cope.”

In a separate study, a team of experts looked at 100 coral reefs around the globe and how often they have had severe bleaching since 1980. Bleaching is caused purely by warmer waters, when it’s nearly 2 degrees (1 degree Celsius) above the normal highest temperatures for an area.

In the early 1980s, bleaching episodes would happen at a rate of once every 25 to 30 year. As of 2016, they now are happening just under once every six years, the study found.

Bleaching isn’t quite killing the delicate corals, but making them extremely sick by breaking down the crucial microscopic algae living inside the coral. Bleaching is like “ripping out your guts” for coral, said study co-author Mark Eakin, coordinator of the Coral Reef Watch program for the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Guam has been one of the hardest places hit with eight severe bleaching outbreaks since 1994, four of them in the last five years, Eakin said. The Florida Keys, Puerto Rico and Cuba have been hit seven times.

It takes time to recover from bleaching, and the increased frequency means coral doesn’t get the chance to recover before the next outbreak, Eakin said.

Only six of the 100 coral reefs weren’t hit by severe bleaching: four around Australia, one in the Indian Ocean and another off South Africa.

Georgia Tech climate scientist Kim Cobb, who studies reefs but wasn’t part of this international team, applauded the research and said that as the world warms more there will be “profound and lasting damage on global reefs.”