A sense of Wanda

WANDA’S JOURNEY. Created by Melvin Pollero of the artist group Tambisan sa Sining and given to the family of Wendell Gumban, this painting depicts his journey from student leader to trade unionist and finally red fighter in the mountains of Southern Mindanao. ALL PHOTOS courtesy of the Gumban family, except as indicated.

When everyone was asleep, Wendell walked to the waterfall. He lay down his weapon, shed all his clothes, and took a dip in the rock pool.

He would later tell a friend a secret—that sometimes he would swim naked at night, float on his back and stare at the dark sky, “mesmerized by the light of the moon.”

Could he have imagined, while he was still living in Manila as a university graduate, that he would end up living deep in the rainforests of southern Mindanao? Living—and dying? On July 23, 2016, Wendell Gumban died in a firefight with the military; he was 30.

Communing with nature was only one part of Wendell’s life in the countryside. Most of his time was spent hiking to far-flung barrios of lumad, the indigenous people of Mindanao, and teaching them how to plant rice and vegetables, how to read and write.

The middle child of a middle-class couple, the University of the Philippines graduate and Philippine Collegian managing editor was invariably described by friends and acquaintances as intelligent, hardworking, brilliant.

Article continues after this advertisementTo his parents, he was Weng, simple and “kind but (inconceivably) brave.”

Article continues after this advertisementTo his friends, he was Wanda or Shala, the student leader who defied stereotypes.

To the lumad, he was Ka Waquin, who left the comforts of the city to live with them. Bespectacled, lanky, and fair-skinned, he was not your typical tibak (activist).

He was Weng, Wanda, Waquin. UP graduate. Gay. New People’s Army rebel.

Wendell

“In the 21st century, it is rare to hear of UP students or graduates joining the NPA,” UP Diliman Chancellor Michael Tan would write in his Inquirer column, after news of Wendell’s death spread. “But it does happen, and when I do get news of someone from UP being killed in an encounter, I pause and reflect, wondering why UP students join the NPA; or, for that matter, why we continue to have an armed insurgency.”

Wendell died two months shy of his 31st birthday—and two days before the Duterte administration declared a ceasefire with the NPA, the armed wing of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP).

“In the 21st century, it is rare to hear of UP students or graduates joining the NPA,” UP Diliman Chancellor Michael Tan wrote.

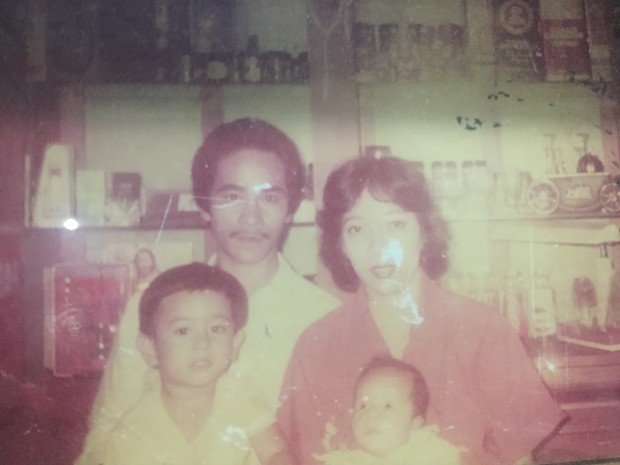

Wendell was born to Edna and Nestor Gumban in 1985, a tumultuous year for Philippine society, on September 22, a day after the traditional anniversary of the proclamation of martial law,

Edna recalled how a massive transport strike blocked main access roads in Bacolod, where she was temporarily staying. The roads were cleared of barricades only a day before Wendell was born. Five months later, millions of Filipinos would leave their houses to force Ferdinand Marcos out of office. Edna and her husband Nestor, who used to be a student activist, were among those who converged on EDSA.

After the People Power Revolt, the two went back to their old life, working for private companies. They would show their children photos from that historic event and would sometimes bring them to Camp Crame and Camp Aguinaldo, but it was Wendell’s first-hand experience in UP, they said, that made him politically aware.

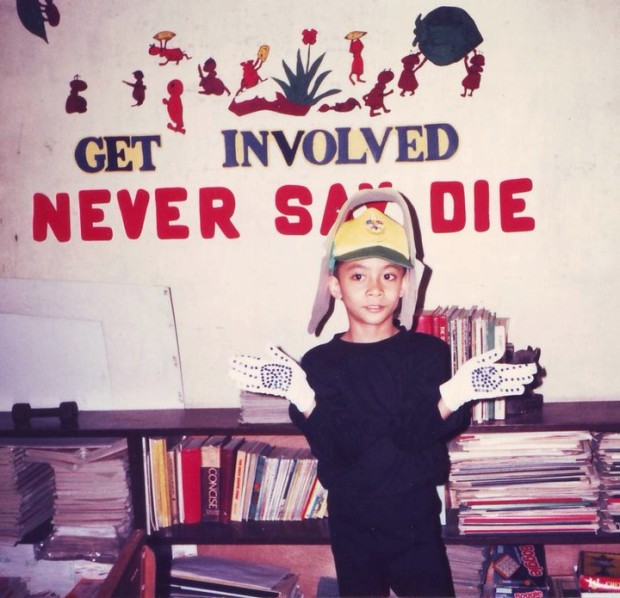

As a child, Wendell was “simple, kind, and smart.”

“Mabait pero matapang. Never ‘yan umiyak (He was kind but brave. He never cried),” Edna said.

His brother said he was a cheerful child who worked hard. Unlike other children, Wendell did not ask for toys or clothes. On his birthday or for Christmas, he would ask for books.

“He never demanded (anything),” Edna said. “He would wear his old clothes repeatedly.”

Nestor pointed out that they could afford to enroll their children in a private school (Wendell and his two siblings studied at Lourdes School), but his second child wore the same set of uniforms throughout high school.

Edna said she always wondered why Wendell was like that. In UP, he never asked for money and their only expense was for his tuition and transportation.

Wendell was silent but he was an active child. Once, Edna accompanied him during a field trip and she was surprised when Wendell volunteered and went in front to recite a poem.

“Tahimik siya pero nandoon sa loob yung pagiging leader nya (He was quiet but you could see that he was a leader),” she said.

TRIBUTE. Friends and activists pay tribute to Wendell/Wanda/Waquin last August 4 at the Church of the Risen Lord, University of the Philippines, Diliman. In the background is a flower arrangement from the Communist Party of the Philippines. Photo by Kristine Angeli Sabillo/INQUIRER.net

Wanda

In 2002, Wendell got accepted into UP Diliman.

He joined the campus paper, Philippine Collegian, a year later, becoming a news editor and then managing editor in 2006.

Friends from the Collegian recalled how Wendell was exposed to the different issues roiling the campus — from tuition fee hikes to demolitions of nearby urban poor settlements.

He would explain different issues to fellow writers in a bid to enlighten them.

One of his colleagues, Lisa Ito, said Wendell was very diligent in chasing the news; once, she recalled, he was even chased by a goat while covering an event at the UP Arboretum, a man-made forest area within the campus.

At his wake, friends recalled how Wendell would always wear a collared polo, slacks and leather shoes. Despite this “formal” get-up, however, he still led a simple life.

“Designer po at branded ang kanyang mga bag kasi ang brand noon SM, Shopwise (His bags were designer and branded because the brands were SM, Shopwise),” Vencer Crisostomo, former League of Filipino Students (LFS) national chair, joked.

“He was fond of walking around the campus to get to his sources, a plastic shopping bag with his things in tow. By most accounts, he never owned a proper bag,” another Collegian writer, Margaret Yarcia, said.

Inside the bag were his slippers and overnight clothes.

Wendell would spend many nights in UP, first to help in the Collegian presswork and later to attend late-night meetings with other activists.

The Gumbans lived in Metro Manila but Nestor said Wendell would sometimes stay out for five nights straight. He did not tell his parents where he went. One time, Nestor went through his son’s drawers and saw a stack of leftist readings.

“He was coming to terms with a huge part of his persona,” a friend said.

Wendell led a colorful life in UP, as colorful as his flowery umbrellas and violet bags.

A fellow activist, Mark Ambay, said Wendell’s accessories would catch their attention and eventually lead them to recruiting him into the LFS.

Ambay, who is also gay, said he and Wendell were a “tag-team.” Wendell’s quiet nature complemented his talkativeness.

They would spend hours discussing student organizing and various political issues. Wendell became more active in LFS at the height of calls to impeach President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo.

Ambay said they would also talk about how it was to be gay at a time of struggle and how they could be accepted by their family and society at large.

Wendell had a flair for theatrics. Ito recalled how on sleepless nights he would wrap himself in a blanket and pretend that he was a beauty pageant contestant in the long gown competition.

Yarcia said Wendell would also occasionally “unbutton his shirt and knot the hems together, revealing his chest and midriff. He would dance on the tables in ‘performances’ that delighted us.”

“Now that I think about it, they might have been more for himself than for us. He was coming to terms with a huge part of his persona,” she said.

Despite the simple and happy life that he lived, Wendell faced a lot of important life decisions.

Instead of graduating in 2009 (already delayed since he shifted to a tourism course), he skipped two semesters to work as a full-time activist.

He volunteered to work with trade unions and would write press releases for them.

Bong Labog, chairperson of Kilusang Mayo Uno, said Wendell wrote high-quality articles.

Of course that did not mean that he did not have weaknesses, Labog said during the wake.

He pointed out, to the amusement of the audience, that Wendell was slow in eating, slow in bathing and slow in waking up.

Still, Labog said they saw how much Wendell loved being with and serving the masses.

In the mountains of Southern Mindanao, Wendell would be reunited with Ka Ben, an old acquaintance from Manila.

One labor leader said many media practitioners were also impressed with Wendell’s writing and communication skills.

His parents, on the other hand, would be surprised whenever they heard Wendell giving interviews on the radio or on television.

But another friend said Wendell preferred working closely with the people, instead of trying to reach them through media.

He preferred being at the center of action, in union offices and poor communities.

Waquin

In 2010, he graduated from UP with his tourism degree, and companies were calling to recruit him. But after returning from a month-long volunteer project with foreign observers in Southern Mindanao, Wendell told his parents that he wanted to return to the region. This time as a Red fighter.

“Pupunta na talaga siya doon, mamundok na siya talaga (He said he will go there. He will go up the mountains),” Nestor said. Wendell’s parents understood what he fought for as a student and an activist, but they did not expect him to join the NPA.

Ka Ben posted a letter on the website Pinoy Weekly recalling his time with Wendell. He (Ka Ben) experienced “extreme culture shock” when he moved to Mindanao. He found himself in an encampment literally wallowing in mud, with comrades who had difficulty communicating with him. It was Wendell, who by then had taken the name Ka Waquin, who helped him adjust.

“We would march through small villages with curious eyes and beaming smiles while venturing up impossibly high mountains, with waterfalls and the sounds of the forest all around us. It was physically challenging, but good for the soul.”

One time, Ka Ben asked him about the name “Waquin.” Wendell replied: “Oh, it means ‘Wak-Wak Queen!”

“Wendell the Wak-Wak Queen of Mt. Diwata!” Ka Ben wrote.

Even in the mountains, Wendell did not lose his love for gowns and flowers. Once, he was assigned to organize a wedding for a pair of rebels.

“This was a task that he relished and took very seriously. He made beautiful bouquets of flowers found in the forest, and decorated the whole camp,” Ka Ben said.

The camp was surprised, however, when he wore a sarong as a mini-skirt one day.

“We did not want to stop him from expressing himself. But most of us were nonetheless relieved that the mini-skirt was worn for just that one day, and then replaced with the more conventional hiking shorts and botas (boots) the next. Anyone who had seen his chicken legs will understand why,” Ka Ben wrote.

It was to Ka Ben that Wendell shared his secret skinny-dipping experience at the waterfall.

Political instructor

Guerilla Front 25, to which they belonged, was in the mountainous boundary of Davao Oriental and Compostela Valley.

“Visually, it was beautiful,” Ka Ben said. “We would march through small villages with curious eyes and beaming smiles while venturing up impossibly high mountains, with waterfalls and the sounds of the forest all around us. It was physically challenging, but good for the soul.”

He said Wendell took his role as an educator seriously, especially after realizing that the lumad were used to having the NPA around.

This was the opposite of people in the cities, Ka Ben said, who find the revolution “very abstract.”

And while they were happy that the lumad considered them part of their daily lives, the lumad did not care about the NPA’s goal of overthrowing “a very distant reactionary state.”

“Waquin saw the importance of his task as an educator who assists the people in raising their consciousness on the long-term gains of the revolution and on the need to not to be content with just the here-and-now,” Ka Ben said.

From time to time, Wendell would message his parents and assure them that he was safe. For their part, they would try to convince him to return to Manila and work for cause-oriented groups instead.

In 2013, the couple finally decided to visit him; it was their chance to see how his life was in the mountains, to check if he was well. Their bunso (youngest) had only one request: Bring her kuya (older brother) home.

The experience was an eye-opener for Nestor and Edna.

The lumad community they went to was truly remote. From the highway, they had to ride a motorcycle for almost four hours. And then they had to hike uphill for another two.

In that village, the NPA served as the community’s school and court.

“Doon namin nakita ang pagmamahal nila kay Wendell (That’s where we saw the people’s love for Wendell). He was well-loved and respected by the farmers, lumad, and his comrades,” Nestor said.

The rebels would wake up at 4 a.m. and would hold meetings three times a day. Wendell, who by then had already been promoted to political instructor, would usually conduct training sessions.

They had trainings on organic farming; they also went on medical missions.

The couple said they were surprised to see the NPA providing circumcision, reflexology and acupuncture services.

Edna said organic farming was especially valuable to the lumad whose traditional source of income was abaca.

“Hindi sila marunong mananim. So gutom sila lagi (They do not know how to plant. So they’re always hungry),” she said, adding that many were also illiterate and would be duped by companies into selling their land for just a few sacks of rice.

Wendell studied the language of the lumad so he could teach them how to read and count.

Edna said Wendell’s NPA unit was also able to set up a rice mill in one of the villages.

When there was a land dispute, the NPA court would settle it. This was a faster option for the residents who had difficulty going to the town proper and knew how slow the judicial system was, Nestor said.

Still, after seeing how difficult life was in the mountains, they asked him to return to Manila .

“Wala silang suweldo doon sa bundok. Alam mo naman ang pagkain doon, morning noon evening gulay doon (They didn’t have any salary and their food was vegetables morning, noon and evening),” Nestor said. In the five days he and Edna stayed there, they were able to eat fish only once—and that was because somebody bought it at the market.

There were no toilets in the village, and the source of water was a spring, which was far from their camp.

But Wendell refused to leave.

“Daddy, marami pa akong gagawin dito (I still have a lot to do here),” Nestor recalls his son telling him.

Revolutionary process

For intellectuals like Wendell, the decision to join the revolution is a “process” that involves developing or expanding one’s understanding of society, National Democratic Front (NDF) consultant Benito Tiamzon told the Inquirer.

It usually starts with theory and an understanding of both history and the overall situation of society. “It is when an intellectual immerses himself in the plight of the masses that the theories become concrete and the principles become their own reality,” said Tiamzon, who was also a writer for the Collegian during his time.

“Tapos yun na mismo yung araw na araw na nagiging buhay mo. Hindi ka na makaisip ng buhay na iba pa (That becomes your day-to-day life. You can no longer think of another way of life),” he said.

Asked why the Communist Party of the Philippines, the NDF, the NPA, and armed struggle remained relevant, he said it was because there was severe poverty in the country.

“In the Philippines, the poor have no dignity,” he said, quoting foreigners who recently shared their observations with him.

Wilma, Tiamzon’s wife and also an NDF consultant, said people who decide to take up arms are the ones who have lost hope in the system and who believe that it should be replaced.

She said that what the NPA imparts to the poor is the understanding of strength. “Masyado kasing hiwa-hiwalay ang mahihirap. Kailangan nilang magtipon ng sariling lakas (The poor are scattered. They need to come together, gather their own strength).”

Tan said he understood how Wendell was radicalized in UP.

“UP, a public university, would have exposed him to classmates struggling with finances,” he said. Wendell would have also seen “the sheer poverty of people amid the rich resources that have made Mindanao the Promised Land.”

He said that while people might disagree with the armed struggle, “it is difficult not to admire, or at least respect, Ka [Waquin] in the way he was so driven by what comes close to, but surpasses, religious vocation.”

For intellectuals like Wendell, the decision to join the revolution is a “process” that involves developing or expanding one’s understanding of society

In 2004, Wendell wrote a piece for the Collegian titled “Kumpisal ng Isang Reporter (Confessions of a Reporter).” In it, he tackled the dilemma of playing the role of both journalist and activist.

“Kung susuriin ang mga detalye, kung titimbangin ang mga opinyon, at posisyon sa iba’t ibang anggulo, alam kong may mas malaking katotohanan, mas masalimuot na tunggalian (If we analyse the details, if we weigh the opinions and positions from every angle, I know that there is a greater truth, a more complex conflict).”

Greater truth

According to the NDF, Wendell died in a firefight against the Army’s 66th Infantry Battalion in Sitio Pong-pong, Brgy. Andap in New Bataan, Compostela Valley.

Sitio Pong-pong is located at the foot of the 8,760-feet high Mount Tagubud, a lush mountain that serves as a source of the Agusan River.

News reports said four people died during the July 23 encounter between the 66th IB and the NPA’s Guerrilla Front 25 — two soldiers and two rebels. The firefight lasted 45 minutes before the rebel forces retreated.

Wendell’s family and friends recall a more personal, human story — of Wendell dying alongside a lumad fighter named Sario “Ka Glen” Mabanding, of Ka Glen using his body to shield Wendell from the bullets, of Wendell telling his comrades to leave him, lest his fatal injuries slow the group down as they retreated deep into the forest.

Edna said they knew something was wrong when an old colleague of Wendell’s asked to meet with them on July 27, her birthday. They met in a restaurant and were given the runaround for 30 minutes before they were finally told of his death.

At that time, no one knew exactly what had happened.

Wendell’s parents arrived in Davao to discover that farmers were guarding their son’s remains in the morgue after the military refused to cooperate.

Edna said the autopsy revealed that the bullet that hit Wendell failed to exit, breaking his ribs and injuring his lungs in the process.

Despite accepting his son’s decision and understanding what had happened, Nestor said he could not help but cry. “I still cry — five or six times each day,” he told the Inquirer, a week after Wendell’s death.

Edna said she wanted to talk to the military, especially the unit that killed her son.

“Gusto ko silang maharap kung ano ba talaga ang pinaglalaban nila, kung may kasalanan ba si Wendell sa kanila (I want to face them to ask what they are fighting for and what Wendell did to deserve this),” she said.

Edna said she hopes that the peace talks succeed and for both the military and the NPA to be disarmed.

He said their family was very thankful to the many people who expressed their love for Wendell and who gave him a tribute not only in Manila but also in Davao and Bacolod.

In Manila, the mood was light, with friends and family recalling Wendell’s humor and cheerful disposition in life.

In Davao, farmers and lumad talked about how they benefited from Wendell’s work. Edna said it was only then that they realized how much Wendell had done for the community and how many far-flung villages his unit had reached.

“If you ask me how he died, I will tell you how he lived,” the father said of his son.