Loyal ally is ‘Little Duterte’

But he is simply “Jun” to close friends.

Leoncio Badilla Evasco Jr., 72, is still uneasy with the fame that goes with being a Cabinet secretary of the Duterte administration. “I am not used to it. I haven’t adjusted yet,” he said.

Before his appointment to the official family of President Duterte, Evasco was a priest, a communist rebel and a political detainee during martial law in the 1970s.

He later became a trusted ally of then Davao City Mayor Rodrigo Duterte whom he served for several years before returning to his hometown in Maribojoc, Bohol province, to run for mayor. He was on this third term as mayor when Mr. Duterte decided to run for President in May.

Article continues after this advertisementBeing a loyal friend, Evasco served as Mr. Duterte’s national campaign manager. It didn’t come as a surprise that he would be named secretary of the Cabinet.

Article continues after this advertisementEvasco and Mr. Duterte may have clicked because they have a lot in common. Both are strict and stern disciplinarians, as well as brilliant strategists.

Like his mentor, Evasco displayed determination and iron will, along with a powerful sense of duty and a dedication to hard work.

“He (Evasco) knows what he is talking (about),” said Fructuoso Redulla Jr., Evasco’s vice mayor in Maribojoc for six years. “He doesn’t tolerate foolishness. He gets very angry when people in government fool around.”

Favorite cuss words

Evasco is straightforward and doesn’t hesitate to point out to a person his mistakes.

And like the President’s language, his can be colorful and mean. Putang ina (son of a bitch) is also Evasco’s favorite cuss words.

“You better shut up or else maputang ina jud ka ana niya (He would tell you ‘you’re a son of a bitch’),” said Redulla, who was scolded by Evasco for making a bad decision.

“Whenever you decide on something, stick to that decision. You can argue with him if you know you are right and he will give you the chance to execute your decision,” he said. “You should not be fickle-minded or he will call you ‘putang ina.’”

Redulla acknowledged that the President and Evasco were “exactly the same, like peas in a pod.”

“Perhaps it was him (Evasco) who influenced Duterte,” he added.

Management skills

Evasco shows warning signs when he is already at boiling point.

To show that he is listening, he curls his fingers to form a fist, his thumb resting on his chin. When he places an index finger on his lips, it is time to shut up or get severe tongue-lashing.

Evasco has exceptional management skills, Redulla said.

During the presidential campaign, he mapped out the overall campaign strategy, which was initially underestimated by other candidates.

Evasco was noticed only when Mr. Duterte won. But by then, it was already too late.

They didn’t know that this probinsiyano (country bumpkin) comes from a good family in Maribojoc, a fourth-class municipality of about 20,000.

He studied philosophy and theology at Seminario Mayor de San Carlos in Cebu City and took up graduate studies at Ateneo de Davao University. He was ordained in 1970 and was assigned to various parishes in Bohol—Dauis, Baclayon and Catigbian towns.

Then martial law was declared in 1972.

The young priest joined the communist New People’s Army after his convent in Catigbian was raided by soldiers in 1974.

In 1983, he was among the four rebels who were arrested in Davao. He was the lone survivor, though the torture he suffered made him wish that his captors should have just killed him.

It was then that he met Mr. Duterte, city prosecutor of Davao, who took pity on him. Their friendship started.

When dictator Ferdinand Marcos and his family were ousted in the 1986 Edsa People Power Revolution, Evasco was among the political prisoners who were freed. Then Mayor Duterte hired him to work in Davao City, serving in various positions—acting city engineer, head of Davao City Economic Enterprise and chief of staff—from 1989 to 2007.

He was with Mr. Duterte even when the latter was elected congressman from 1998 to 2001.

Evasco decided to go home to Maribojoc and serve the town that had been good to his family. He won by a landslide and implemented changes there.

Leading by example

Sensing the lackluster performance of some employees, Evasco led by example to show the importance of diligence, punctuality and honesty in public service.

Amor Maria Vistal, who was the private secretary of Evasco, recalled that his boss was the first to report for work and the last to leave the office.

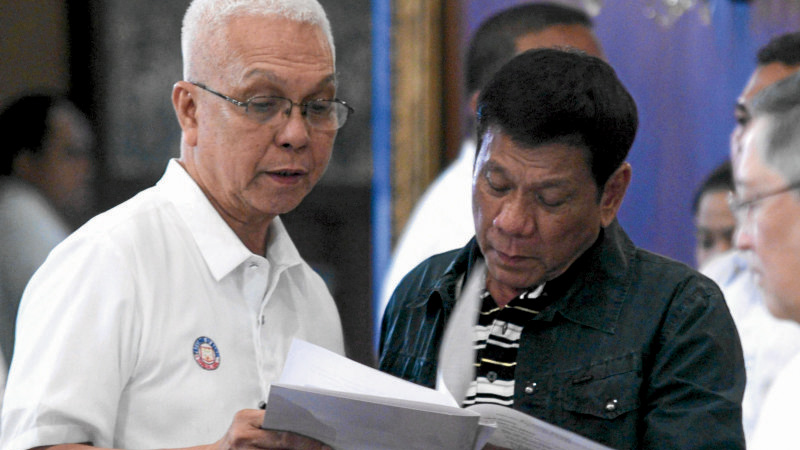

LIKE-MINDED President Duterte and Cabinet Secretary Leoncio Evasco Jr. are both strict and stern disciplinarians and brilliant strategists, and share favorite cuss words. PALACE PHOTOGRAPHERS DIVISION

“Mayor Evasco talked with his heart on his sleeve and knew almost everyone in town,” Vistale said.

Even before the “anti-epal” movement became famous, Evasco was one of the few mayors who didn’t want to put his face on government projects.

Aside from implementing a curfew in 2007, he didn’t hesitate to punish abusive relatives. He earned the reputation of driving away drug dealers from his town.

Redulla recalled that an engineer, who had a project in the town, left an envelope full of cash for Evasco, who turned it down.

A simple man, Evasco is easy to please. A bowl of law-uy, a vegetable-based soup dish, makes him happy.

During his term as mayor, the Department of the Interior and Local Government awarded Maribojoc twice the Seal of Good Housekeeping—in 2010 and 2011.

His management skills were put to a test when Maribojoc was among the towns ruined by a 7.2-magnitude earthquake on Oct. 15, 2013, that brought Bohol to its knees.

Evasco was able to deliver assistance to victims and mount rehabilitation efforts without relying on the national government.

He didn’t get any help being an opposition mayor. So he sought assistance from his friends, including Mayor Duterte.

He organized a municipal-wide relief distribution network that distributed relief goods among the earthquake victims regardless of party affiliation.

On the sidelines

When volunteers of the Philippine Red Cross wanted to bypass the municipal’s relief distribution network, he drove them away.

Evasco still had several unimplemented projects in Maribojoc. These included an international port and a “floating market” for organic vegetables and fruits. Roads in some remote villages remain rough.

Now that he is in Malacañang, Evasco prefers being on the sidelines. “I am here to work. I am paid by the people to work,” he said.

He has only one promise to Boholanos: “Dili ko magpakaulaw ninyo (I will not embarrass you).”