Batangas museum rises for Mabini

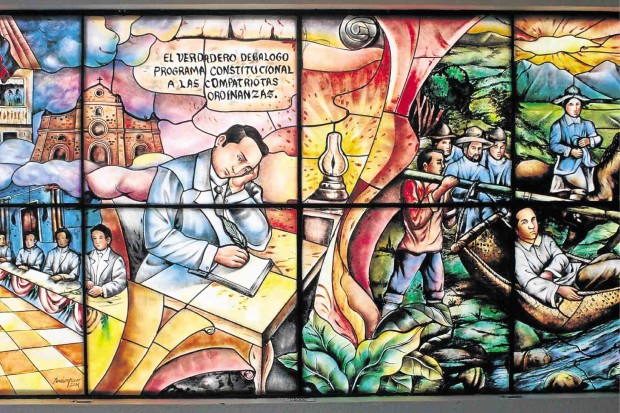

A STAINED glass display at the Mabini Shrine in Tanauan City shows Apolinario Mabini writing “El Verdadero Decalogo” (The True Decalogue), a set of rules to guide Filipinos on how to become better citizens, in May 1898. MARICAR CINCO /INQUIRER SOUTHERN LUZON

TANAUAN CITY—Ever wondered why, in the very few photos of him, Apolinario Mabini’s head was slightly turned sideways? This was not coincidence.

It is said, at least within the hero’s family, that Mabini’s left eye was slightly defective, “a bit squinty” that, to conceal it, he would pose sideways when his photograph was taken.

This was one of the little-known details about Mabini, the polio-stricken “brains” of the Philippine Revolution who was among the key figures in the country’s fight for independence. Unlike other Philippine heroes such as Dr. Jose Rizal or Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo, Mabini did not have as much photographs taken when he was young.

“They were very poor,” said Olga Rizal-Palacay, curator of the Mabini Shrine in this city in Batangas province, about 70 kilometers from Metro Manila.

The second of eight children of a poor, peasant couple, Mabini, as a young man, took on odd jobs, like being a farm hand or a househelp, to finance his education. His mother, Dionisia Maranan, sold coffee in Lipa City, a 10-kilometer walk from their home in Barangay Talaga here.

Article continues after this advertisement“When there’s more left to sell, the mother would sleep over friends’ houses in Lipa and be back on the streets the next day. Imagine that kind of living,” Palacay said.

Article continues after this advertisementIn school, Mabini was regarded as the poor kid in worn-out clothes who never owned books but did well in class. His grades were almost always marked with “sobresaliente” or excellent.

“They said while all the other children played, Mabini would pick up a book and read,” Palacay said.

To keep himself awake to study at night, Mabini would soak his feet in water, a habit that his family believed may have contributed to his acquiring polio, leading to the eventual paralysis of his lower body at the age of 32.

Wheelchair-bound

Mabini had always been portrayed as the wheelchair-bound hero, who served as foreign minister and adviser to Aguinaldo.

Actor Epy Quizon, who portrayed Mabini in the 2015 historical epic, “Heneral Luna,” voiced out his frustration on Facebook when a group of college students asked him why his character was seated throughout the film.

Palacay, apparently, had a similar experience.

“I was watching (Heneral Luna) when I overheard a group of students asking why Mabini’s character was always sitting. I can’t describe how I felt. It was only towards the end of the film when they (students) realized who Aguinaldo was (portrayed by actor Mon Confiado),” Palacay said.

Museum

“We cannot blame these teenagers [for not knowing Mabini] given all these distractions, like shopping malls or the internet. But there really is a need to inculcate in these young minds the sacrifices they (Philippine heroes) made,” said Pelagia Mabini, 68.

Pelagia, a third generation descendant of Mabini through Mabini’s brother, Monico, worked 42 years guiding tourists at the shrine’s museum.

The museum was built on June 23, 1956 on a 1.1-hectare lot that the government bought from about four families of the Mabini clan. It was an empty, old building until the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP) in July 2014 renovated the facilities into an interactive and modern museum, in time for Mabini’s 150th birth anniversary,

The Mabini museum now has seven galleries with an audio-visual room, a stereoscopy room of copies of photographs of the Philippine Revolution from 1896 to 1898, push-button exhibits, and a hologram display of Mabini.

From an average of 25,000 guests in a year before the renovation, 121,669 people in 2015 visited the Mabini museum, so far the largest of the 22 historical shrines and landmarks in the Philippines.

“There are a lot more to know about Mabini than his being a paralytic,” Pelagia said.

For instance, she said “Lolo Pule,” as they referred to Mabini, was a patient and quiet person.

“He lived a very simple life. He loved ayungin (fish) and talbos (camote tops),” Pelagia said. Ironically for someone known for his disability, Mabini’s favorite sport was sipa, according to an account by his younger brother, Alejandro.

When Mabini could no longer move on his own, it was his older brother, Prudencio, who looked after him, carrying him and attending to his needs. Prudencio only married after Mabini’s death.

The wheelchair that Mabini used and is now displayed at the museum. MARICAR CINCO /INQUIRER SOUTHERN LUZON

Service

Pelagia said Dionisia wished for her son, Mabini, to become a priest but he wanted to study law. “My guess is that’s one of the reasons he never married,” Pelagia said. “[Mabini] reasoned he could serve other people, even without becoming a minister of God.”

It was on June 12, 1898, the declaration of Philippine Independence, when Aguinaldo and Mabini first met in Kawit town in Cavite province. Aguinaldo sent for Mabini, who was then in Laguna province, to become his adviser.

Despite his condition, Mabini continued serving the government and supported the war against the Americans until he died of cholera in 1903.

Like her Lolo Pule, Pelagia, in her own way, found a way to serve her country, devoting her life to the museum.

“She is married to this museum,” Palacay said of Pelagia. Aside from Pelagia, three other Mabini descendants are also working for the NHCP although they are assigned to other shrines in Batangas and Bulacan provinces.

“I have spent more time here in the museum than at home. Until today, I would still dream about this museum back in its old state where there were there still nipa huts around here,” Pelagia said.

Pelagia wishes that more people, especially the younger generations, to visit not only the Mabini shrine but the country’s historical sites.

Hopefully, she said, it is about time people see the other side of Mabini’s face.