Art gets dirty, smelly for cleaner Pasig River

IN THIS unique art project, the murky medium is indeed the message.

The “Dirty Watercolor” exhibit features exquisite paintings rendered using pigments collected from polluted waterways in Metro Manila, particularly Pasig River and its tributaries, hoping to raise public awareness about their sorry state.

Taking six months to prepare, the 22-piece show depicts contemporary river scenes in blacks, browns, grays, and sepia tones. Viewers can still catch this fundraiser until tomorrow at Kirov Showroom in Rockwell Center, Makati.

The limited palette of colors was sourced from riverbed soil samples taken from Taguig City, Marikina City, Binondo in Manila, and Cainta in Rizal province, among others. They were treated in the lab and mixed with gum arabic solution before they were used in the paintings.

The biggest artwork captures the delight of a child who has just taken a swim in the dirty water but “is unaware that her playground is unsafe,” said the artist, JC Vargas, of his work titled “Sabina”.

Article continues after this advertisementUsing the pigments presented a unique challenge for him. “Smelling the paint already tells you a lot about the lives of the people living by the river or estero.” The stink goes away only when pigments dry off, Vargas noted.

Article continues after this advertisementThe other participating artists are Toti Cerda, Kean Barrameda, Ferd Failano, Allan Clerigo, Van Isunza, Luigi Almuena, Renee Ysabelle Jose and John Ed De Vera.

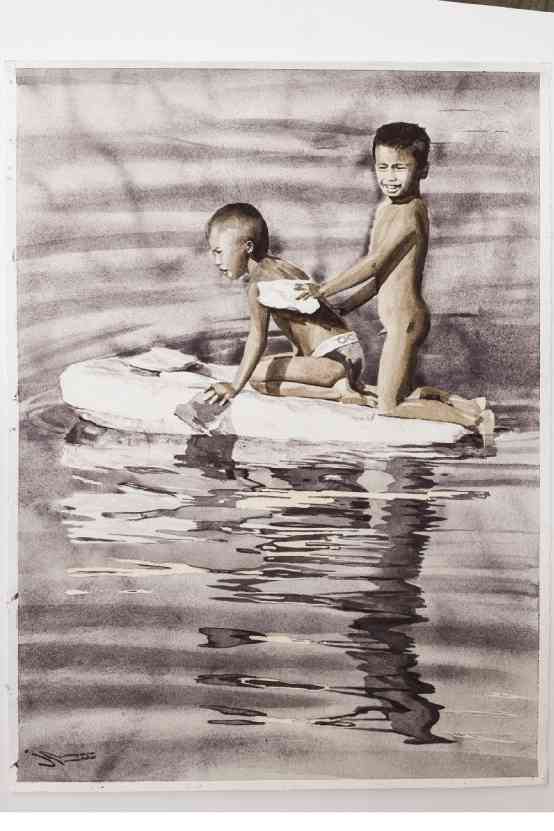

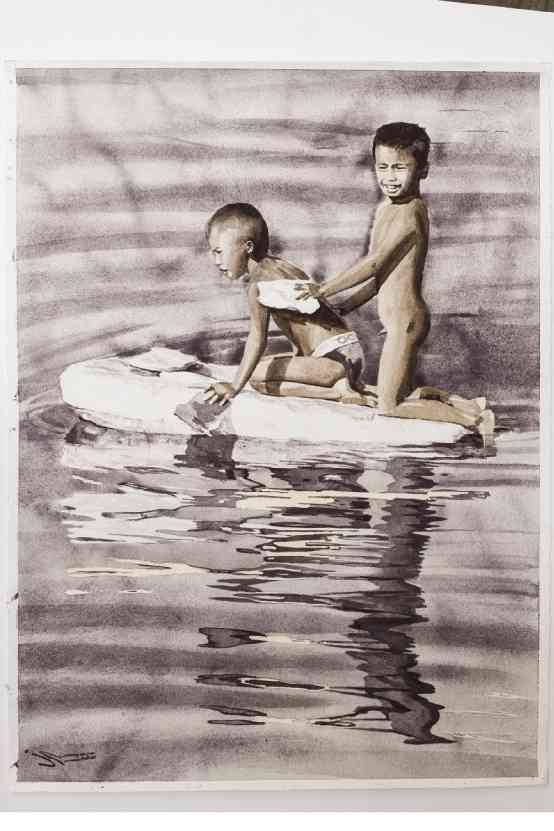

ADVOCACY AFLOAT “Magkaibigan-1” (Friends) by JC Vargas, one of the 22 works featured in the Dirty Watercolor art exhibit TBWA\SANTIAGO MANGADA PUNO

“The Pasig River will be there forever, and generations of Filipinos can watch either its destruction or its salvation,” art critic and curator Cid Reyes said. “They need to be informed how to save it.”

Yeb Saño, executive director of Greenpeace Southeast Asia and former commissioner of the Climate Change Commission, joined the chorus of concern: “There have been a lot of efforts to revive the rivers, but it will take more than just a few people to make this work; it would take all of us. The work of the artists depicts this message in a very clear way. If you combine art and advocacy, it becomes very powerful.”

As highlighted in the Philippine International Rivers Summit in 2012, all rivers in Metro Manila are now considered biologically dead. Commanding most attention is Pasig River, a storied waterway that runs through five cities and 51 tributaries.

Niño Caguimbal, a scientist helping in the campaign, took part in the art project by personally gathering the soil samples from the tributaries. The samples were then brought to the laboratory for filtration, decontamination and drying.

“We had to check if we can actually go down near the rivers to get the samples. We observed first if they were contaminated by human waste or just garbage,” Caguimbal said. “The sediments we collected were mixed with trash and fish bones.”

In the process, he encountered shantytown dwellers and families living under bridges, whose everyday lives in the midst of a poisoned environment supplied the images for Dirty Watercolor.

An executive order issued in 1999 created the Pasig River Rehabilitation Commission, whose main goal is to bring back the water quality to a level suitable for fisheries.

With even artists now lending a hand, it shouldn’t be an impossible mission, Caguimbal stressed: “It may not be fully clean or safe, but if we can start small in the different canals, then we can begin the rehabilitation and main cleanup of the Pasig River.”

ONE OF the artists creates a new painting using the pigments collected from the polluted rivers and tributaries of Metro Manila. JHESSET O. ENANO