‘Emprestito,’ a story of generosity in war

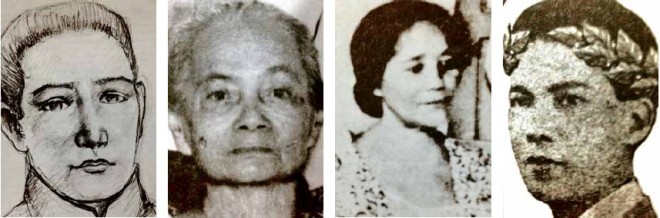

THE PLAYERS “Emprestito” story—(from left) Gov. Tiburcio Hilario, Adriana Sangalang-Hilario, Filomena Hilario Gwekoh and Judge Zoilo Hilario PHOTOS FROM ‘A SHAFT OF LIGHT’

CITY OF SAN FERNANDO—The “emprestito,” a supposed donation of a million silver pesos by Kapampangan to sustain the first Philippine Republic, has remained a family story.

Twenty-four years after Rafaelita Hilario-Soriano wrote about it thrice in her books, that contribution, which is more than double the P400,000 indemnity from Spain that President Emilio Aguinaldo used to revive the revolution, has not yet become part of the official narrative of the Filipinos’ struggle for independence from Spanish and American colonial masters.

When it is talked or written about, the emprestito is reckoned to be the source of the wealth of the Cojuangco clan or is sidetracked to the purported romance between Ysidra Cojuangco and Gen. Antonio Luna, although these were matters that Soriano did not raise in her books, “A Shaft of Life” in 1991, a revised edition in 1996 and “The Pampangos” in 1999.

Soriano, an educator and diplomat, had her grandmother Adriana Sangalang, her father Zoilo and her aunt Filomena Gwekoh as sources on the emprestito.

She interviewed them in 1956 as she wrote a biography of her grandfather, lawyer Tiburcio Hilario, who collected the emprestito when he was the governor of Pampanga in 1898.

Article continues after this advertisementMatea Rodriguez Sioco, Manuel Escaler and Joaquin Gonzales were said to be among the biggest donors.

Article continues after this advertisementSoriano’s relatives said Hilario, in the presence of witnesses, transferred the amount to Luna in the home of the governor’s cousin, Julian Santos, in Tarlac. This happened three days before Aguinaldo’s men killed Luna in Cabanatuan City in Nueva Ecija on June 5, 1899.

Soriano did not mention a document or receipt for the turnover.

In the book’s revised edition, Soriano wrote: “Tiburcio Hilario was on the move again, hoping to save the emprestito for the cause of the revolution.”

From Bacolor, he proceeded to Angeles with his family. In their journey northward, the Hilarios were accompanied by relatives, friends and members of distinguished families in Bacolor.

“But this trip became even more perilous with the huge sum of money he had to transport, amounting to one million silver pesos. When one considers that the rebels from Hong Kong started the Philippine revolution anew with only P400,000, one realizes how significant was the amount [Hilario] transported for the cause of freedom.”

Soriano said the money was made up of “voluntary contributions from the Pampangueños, war bonds and the aid given by Chinese residents in [Pampanga].”

“This sum was well-packed in a trunk four feet long, four feet high and more than a meter wide—made of the hardest wood and of iron. Four carabaos were needed to carry the trunk, pulling the covered cart on which it was loaded. Four armed men were in charge of guarding the trunk,” Soriano wrote.

She said the giving of emprestito to Luna had Aguinaldo’s permission.

“[Hilario] did not do this to side with one or the other but to provide money and prolong the war, with the hope that the Americans would be convinced of the Filipinos’ determination to achieve their independence. Moreover, he had complete faith in Luna’s military ability to serve as chief of staff of the Philippine Army, and believed that military success was in the hands of Luna,” she wrote.

She gave no information how the emprestito disappeared or who exactly recovered it.

“In Tarlac, Aguinaldo’s men and the governor could no longer retrieve the huge amount. No one would admit they had seen the money or that they knew where Luna kept it,” she said.

Soriano, who died in 2007, had hoped that her account on the emprestito would enrich the roles Kapampangan took in the revolution against Spain and in the resistance to the United States.

In the book’s foreword, the late Education Secretary Andrew Gonzalez said the “fate of this emprestito has since been a matter of speculation, but its sourcing is not, thanks to the memories of the author and even sharper memory of her grandmother.”

“We must round out of historical accounts through the perspectives of other actors in the drama, through their memories, through their descendant’s stories, through family memorabilia,” Gonzalez said.

The emprestito, said historian Ambeth Ocampo, is an “interesting family story but not supported by a shred of documentary evidence.”

“Such an amount of money cannot vanish into thin air, and with what I have seen from the former ‘Philippine Insurgent Records,’ all funds of the revolution and the government were meticulously recorded,” he said in an email interview.

“As you can see from Mrs. Soriano’s text, even she cannot explain how this amount in silver was more than that which started the revolution. I would love to believe this story but as a historian I need to be convinced by some sort of documentation rather than hearsay,” Ocampo said.