Bintao who?

According to the UP Diliman campus catalogue, the university in 1962 renamed the building that used to be called the Student Union after one of the country’s most prominent student leaders, Wenceslao Quinito Vinzons.

Vinzons Hall, which is right next to the College of Business Administration on Guerrero Avenue, is the only campus building dedicated to student activities.

The university’s student council had asked for a facility that, like a cooperative, could be managed and later owned by the

students, and so the hall was built in 1957.

As students and administrators have found themselves on opposite sides of the issues, Vinzons Hall has become “a symbol of defiance standing as it does on the opposite side of the administration building, Quezon Hall, at the Academic Oval.”

Article continues after this advertisementBut who is Wenceslao Q. Vinzons?

Article continues after this advertisementNational treasure Virginia Moreno acquaints us with the man who was a student leader, an oppositionist, a governor and a war hero in his short quixotic life.—CBF

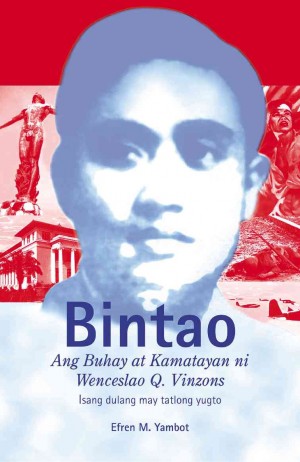

It was Efren M. Yambot’s last drama, “Bintao,” the nickname of Wenceslao Q. Vinzons, his life and death, that with only rusting rifles, sumpak (bamboo cannon?) and, unbelievably, bow and

arrow, fought the enemy as the guerrilla commander in the Bicol region.

Rising, to become the certified genuine folk hero of World War II in the country. But little known and obscured for years because he had died young in battle before he could return after the war to a life, possibly, still a young Don Quixote politician whom no one would be able to malign with that infamous “so young and so corrupt” branding. Thus, the publication of the book and then the first staging of Bintao’s drama by the young Filipinos in the Cordilleras. Their mantra: If not now, when? If not us, who?

When the air squadrons of World War II hovered over Bintao’s little town Indan,

he was already Governor Wenceslao Q. Vinzons of Camarines Norte province in the Bicol region.

I mull on the fate here of Bintao, whatever his patrician origins. He was the son of an hacendero, Don Gavino, and the grandson of an immigrant—not a coolie—of old China from whom he inherited Confucian ethics. In spite of his charismatic leadership in active politics and the visionary causes that he espoused in his shortened life, would Governor Wenceslao Q. Vinzons be accepted now in the League of Governors? Ethnic self-immolation resonates to us from: Ako ay isa lang probinsyanong Intsik from Bicol that one whistle-blower Chinoy said of himself, remember?

Pristine and illumined were Bintao’s early alliances and crucial partisanships—dalisay at magiting, in the poetic words of praise by Yambot, rarely spoken or heard of politicians, governors, congressmen, at iba pa diyan ngayon, etc. …

Wenceslao Q. Vinzons, destiny-wise, was the founder of Young Philippines, the official political opposition party with the first woman candidate for Manila councilor, Carmen Planas, called the “Sweetheart of Manila”; the young lawyer Arturo Tolentino; Salvador P. Lopez, the writer in English who won the Commonwealth Prize for Literature and Society, all of them with their most valued kinship with Ka Amado Hernandez, writer in the paper Mabuhay, militant labor leader, a native of Tondo and therefore the voice of cigarreras, tobacco and cigar rollers, fisherfolk on the Rajah Sulayman beach front, Divisoria fruit and meat bagsak vendors. And, before them, born in Tondo half a century ago, the calesa wheelwright Macario Sakay and the bodegero of an English company who read about the French Revolution, Andres Bonifacio.

No less than the President of the Philippine Commonwealth was the high target of the “Young Turks” of the Young Philippines Party, who were proud to have been secularly, irreverently schooled in the old Padre Faura Street side of the University of the Philippines in the ’30s. Challenging the President, with chutzpah:

“Explain, Mr. President, why the National Assemblymen want to raise their pay? In this midcrisis here and that world crisis erupting out there?” (O, does that ring a bell in us today?)

The besieged President Manuel L. Quezon addressed instead the Ateneo young

students, ecclesiastically, reverently schooled by the Jesuits on their side of the old Padre Faura Street.

“Go south, young men!” Not his message to, by then, human rights lawyer Wenceslao Q.

Vinzons. Neither to the young student of law, Jovito R. Salonga, who will survive the deaths of many Bintaos during the war and live on to be the injured man, but with mind brilliantly intact, as an anti-martial law human rights warrior.

“In 1934, Wenceslao Q. Vinzons was the youngest delegate of the Constitutional Convention,” former Sen. Richard Gordon narrated in his introduction to the book “Bintao.” “I was as

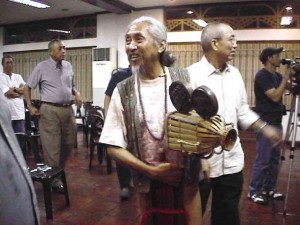

FILM director Kidlat Tahimik pays “ethnic indigenous ritual homage” to his folk hero with a bamboo box camera.

well the youngest delegate in the 1986 Constitutional Convention,” he said.

Imagine, that early, how this young Constitutional Convention delegate among elders, Wenceslao Q. Vinzons, objected to the grant of “emergency powers” to a future president who might, as a dictator, abuse these powers, with a military junta as guardian—unto death—the defenders of the strongman and not of the people of the Philippines.

(O does that ring tocsins, those ancient tower bells warning the remotest hapless coastal towns of our archipelago against marauding pirates / slave abductors / pillagers of women / thieves of homes and harvests, to the last wailing pig?)

Isolated as we were, in smaller battles on our island, from the World War raging in vaster continents elsewhere, prophecies warning artists and writers to flee wastelands never reached us until too late—long after the end of the war, from reading Ernest Hemingway’s novel “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” seeing the victims of Guernica’s bombing painted by the incensed Spanish Pablo Picasso to the poet John Donne’s foretelling: “No Man is an Island”—Never ask for whom the bell tolls, it tolls for thee!

For us, Bintao was one bell-ringer. But we didn’t know how or why until, now I boast, the larger-than-life portrait of him by Bintao’s first dramatist.

A prophet, declared Efren M. Yambot, when Vinzons, as a charismatic debater, won a prize for his concept Malaysia Irridenta, a regional grouping of the Malay people’s aspirations in colonized Indonesia, Malaya and the Philippines. It was followed later by the prototypical Maphilindo (Malaya, Philippines, Indonesia) of President Diosdado Macapagal’s Asian Policy outreach. And then, the 10-member Asean (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) that ironically, in the June 2009 birthday of Aung San Suu Kyi, the longest-held prisoner of Asean member Myanmar’s military junta, silenced that year its protesting monks. The other nine member states went mute and, in the eyes of the world, fang-less.

(June 6, 2009, “UN’s Ban Ki-moon ends trip to Burma empty-handed,” Philippine Daily Inquirer)

That night in June, I was to expose as guest dramatist the meaning of Bintao, the

persona, to us and what was a quixotic role—the painful, loneliest resurrection from their common graves, the haunting souls of Macario Sakay, hanged in Bilibid Prison; Andres Bonifacio shot in Maragondon; Gen. Antonio Luna assassinated in Cabanatuan, and, a mid-century after them, Wenceslao Q. Vinzons. Heroes now. Yet, all had been betrayed presumably by their own people?

What if a dramatist, a painter and, in the century-old, most powerful art of the modern world, the artist as filmmaker, did not stop their daily life to imagine a second life for these heroes of our forgotten wars? What if Efren M. Yambot never felt in his head the grate of the moose over Sakay’s head? And did not shed his corporate coat and tie, unforgiving of his betrayers, to make Bintao live for us, once more?

In my free, safe-in-Parisian exile after Sept. 22, 1972, stranded in Europe and seemingly untouched by the military junta raging so far away at home, I spent mornings in wet markets hunting for rare herbs and summer asparagus, tripping afternoons from Brasserie Balzar to Café La Coupole, nights euphoric at Cinema Paradiso—while marching every 14th of July, Bastille Day, faithfully with the French on the streets of Place de la Republique. Yes, I did sybaritically all the above. Yet, I did, too, what others never dared to touch—compose stoically the intimate theater of Juan Luna’s agony over the death of his little Rubi —under the public arena of the Indio agonistes in his epic painting “Spoliarium.” The boy Raymond Red, trained by the UP Film Center—Munich Film workshop director Wolfgang Langsfeld—filmed the tragedy of Macario Sakay on a rice-and-tuyo budget. Afterwards, hand-carried “Anino,” the shadow-ghost of an unlikely hero in our day: The theft and loss of a street photographer’s life-making camera, on hard French bread and black coffee budget, won for us, the first Palme D’Or, Grand Prix in the 2000 Cannes Film Festival.

“Bintao,” the playbook was launched by the brotherhood of both Wenceslao Q. Vinzons and its author Efren M. Yambot, the Upsilon Sigma Phi fraternity, its alumni and resident fellows. Fittingly held in Bahay Kalinaw—its folk house architecture recalling the hardwood walls and tiles of Ang Bahay Bato, rightly on the 19th day of June to celebrate the 148th birthday anniversary of the national hero Dr. Jose P. Rizal. Omnisciently, as the day’s news featured the shock and protests of Rizal’s town mates in Calamba over a housepainter’s (whoever?) idea of “eco-greening” the Rizal shrine. “Chartreuse,” sniffed culture and lifestyle writer Barbara C. Gonzales, a descendant of the Mercado-Rizal family, on the controversial color. The town humorist said it all: Since my name is Guinto, may I paint my house gold?

Trust the Upsilonians to make a difference, on this day, and plot a surprise number, to think “out of the box” literally.

After the sedate remarks of the Upsilonian host, into the Bahay Kalinao’s sala and unwary audience segued Kidlat Tahimik. Half-naked on G-string and stomping barefoot to Ifugao beats while toting up and down, slow walking, mock-shooting for life (his other Perfumed Nightmare?), a bamboo box camera! His ethnic indigenous ritual homage, he explained, to the indi-

genius hero Rizal, to his folk hero Bintao and the generations now eternally with the sky gods of the Cordillera mountains.

The artist as filmmaker of a revolution and its heroes, like that of playwright Vaclav Havel’s “Velvet Revolution,” needs the Total Man—“di lang writer pala”—not just any writer, to hunt alive the desaparecidos in the street revolutions happening today. And return the image, the meaning, of the flight after Sakay’s execution, of his families to remote islets without roads, erasing their Sakay names. Even subtler, use the Chinese poet and painter’s trigram: a clear mind, a feeling heart and a knowing hand.

If Bintao is made alive as the film’s hero, relate him at once to the protesting Tibetan monks among the unknown dead only a few moons ago. Believe in immortality, as a true filmmaker, like the good Confucian in the Filipino Bintao and the Tibetans in their monasteries, heavens-high over their assassins below.