Pangasinan farmer builds cacao ‘empire’ from backyard hobby

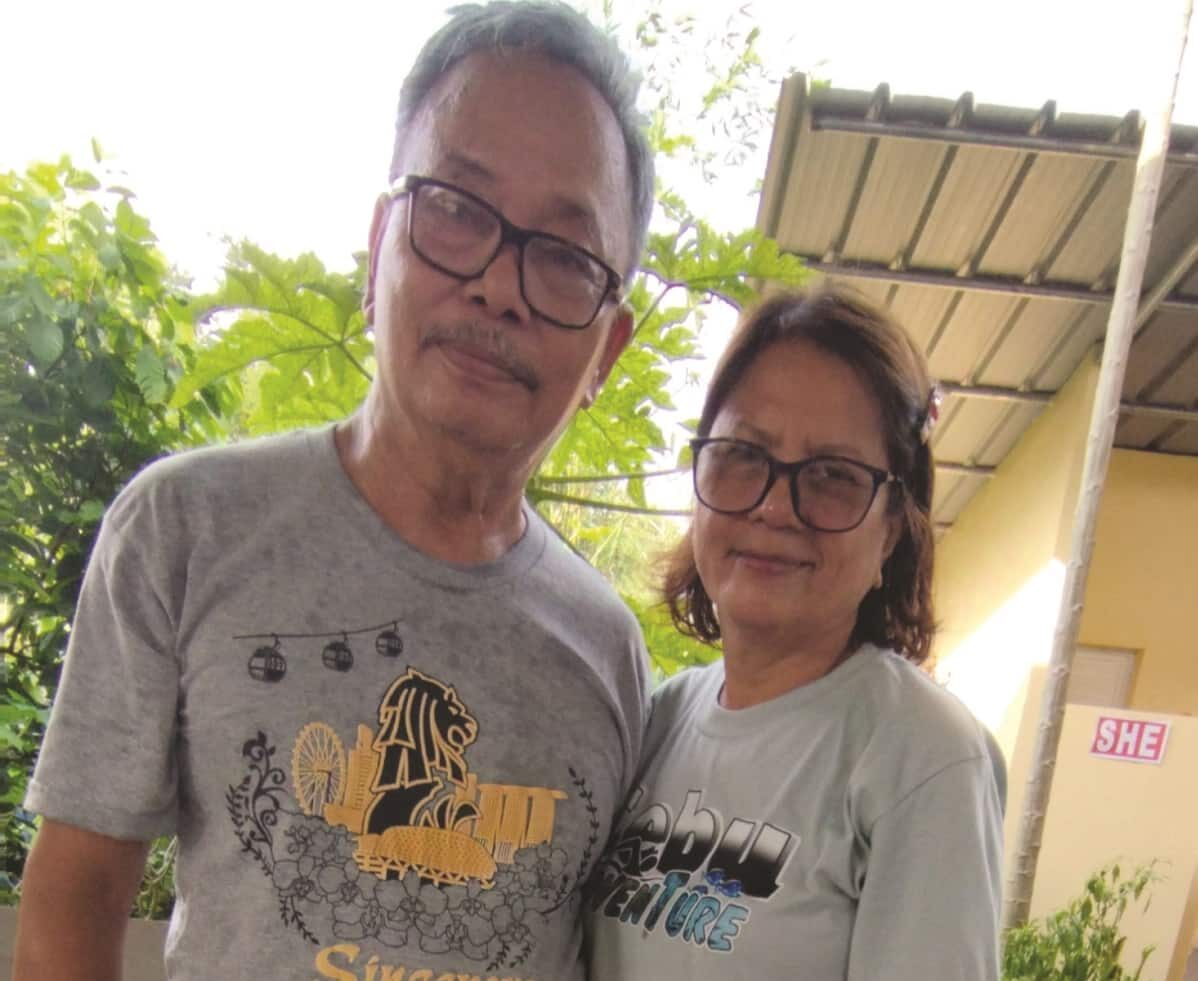

HOMEGROWN Conrado Soriano’s venture into organic cacao farming has given Pangasinan another line of homegrown products that can compete with those produced in provinces popular for local chocolates. —Photos by Ray Zambrano

SAN JACINTO, PANGASINAN, Philippines — Conrado Soriano, 63, finds himself transported back to his childhood as he strolls through his nearly 4-hectare orchard, reminding him of the days when his family’s backyard, filled with cacao trees, was his playground.

“We had 20 cacao trees in our backyard then. My father taught me how to plant cacao. We harvested the fruits and made ‘tablea de cacao,’” Soriano said in a recent interview. “Tablea de cacao” is a traditional delicacy made from roasted, ground and molded cacao beans, ready to be transformed into a thick and flavorful chocolate drink.

As he walked among his cacao trees, memories of sipping fresh, homemade chocolate drinks flooded Soriano’s mind as he went through the daily grind of earning a living and raising a family.

READ: Cacao farmers need more support to boost PH chocolate industry, senator says

In 2011, at the age of 50, Soriano, a marine engineer by profession, decided to reconnect with his roots. He purchased land in central Pangasinan and began planting hundreds of cacao trees.

Article continues after this advertisementWhat started as a mere hobby soon blossomed into a serious business venture.

Article continues after this advertisementCertified

As the cacao trees grew, yielding abundant harvests, Soriano and his wife Myrna decided to expand their vision.

Their farm in San Vicente village stands as a thriving cacao orchard, home to 3,500 trees, producing about 70,000 kilos of cacao beans each year.

Soriano’s Royal Cacao Farm and Training and Assessment Center had been certified as among the organic farms in the Ilocos region.

In August, the farm was awarded a Participatory Organic Certificate (POC) by the Participatory Guarantee System (PGS)-Pangasinan Philippines Inc.

The Soriano farm is the second in Pangasinan to receive certification as an organic farm. The first to earn this distinction is JMS Crops Farm, a 2,000-square-meter farm located in the village of Warey in Malasiqui, Pangasinan. JMS Crops was awarded a POC in January by PGS-Pangasinan.

Owned by Marlyn Inasoria, JMS Crops produces hot green and red peppers, turmeric, tomatoes, eggplants, string beans, okra, taro, and pechay.

Additionally, JMS Crops was accredited in September as a producer of organic fertilizers, including soil amendments, organic foliar 1 (for growth), and organic foliar 2 (for flowering).

At the Royal Cacao Farm and Training and Assessment Center, the Soriano family has also planted a variety of fruit-bearing trees, including avocado, guyabano, pomelo, chico, bananas, and jackfruit.

Soriano is proud to say that his cacao trees since these were planted, have remained untouched by chemical fertilizers and pesticides.

The PGS, according to the Department of Agriculture (DA), is a certification mechanism designed to recognize small farmers, fisherfolk, their associations, and cooperatives engaged in organic agriculture and the production of organic products.

Across different provinces, accredited PGS core groups, recognized by the Bureau of Agriculture and Fisheries Standards, serve as certifying bodies for farms producing organic vegetables, fruits, and processed organic goods.

Receiving a POC means that a farm or company is fully compliant with the Philippine National Standards for Organic Agriculture, the internal standards of the local PGS, and other relevant regulations governing organic farming practices.

Dr. Marvin Quilates, the regional organic farming coordinator for the DA in the Ilocos, said Pangasinan and San Fernando City in La Union province are the only areas in the region with PGS certification.

Meanwhile, Ilocos Sur and Ilocos Norte are still in the process of securing their certifications.

Currently, there are 12 organic-certified farms in the region—seven in Pangasinan and five in La Union.

SHIFT A marine engineer by profession, Conrado Soriano (shown with wife Myrna) in 2011 chose to devote his time tending to a 4-hectare cacao farm in San Jacinto, Pangasinan.

Steady growth

Quilates acknowledged that the organic agriculture program in Ilocos, which promotes farming without chemicals or synthetic inputs, had been slow to take root but was gradually gaining momentum. With 12 certified organic farms covering a total of 15.2 hectares, the movement is starting to sprout.

Despite the region’s expansive agricultural landscape, the number of ha dedicated to organic farming remains small.

“While 15.2 ha is a modest achievement, we consider it a solid start and more farms are in the pipeline for certification,” Quilates said.

Achieving organic certification is no easy feat. Farmers must undergo a rigorous process before receiving the coveted POC.

Even something as small as a piece of plastic found during an inspection, Soriano said, could disqualify a farm from certification.

The Royal Cacao Farm is a pioneer in cacao farming in Pangasinan, cultivating three varieties: Trinitario (using planting materials from Soriano’s family backyard), Criollo, and UF. The farm is also the first in the region to cultivate white cacao beans and the first in the country to grow this variety organically.

The farm’s cacao beans are processed at Cocoa Federico, a plant in Mangaldan town named in honor of Soriano’s father. The beans are turned into both sweetened and unsweetened “tablea,” as well as cacao nibs.

The plant’s latest innovation is cacao vinegar, a byproduct of the fermentation process of cacao beans.

Challenge

Despite the growing interest in organic farming, marketing organic products remains a significant challenge.

Bernie Trinidad, DA Ilocos market specialist, pointed out that organic products often come at a premium, which can deter consumers.

The price difference stems from the fact that organic farming is labor-intensive, and labor costs are higher, Trinidad said.

“For instance, weeds are easier to control with weedicide, but organic farming requires manual labor to remove them,” he noted.

Additionally, converting a conventional farm to organic certification requires a minimum of three years of being completely chemical-free.

“But we are encouraging organic farmers to align their prices more closely with the inorganic produce. And we are asking the government to provide interventions like mobility or vehicles for delivering their produce,” he said.

The lack of consumer awareness poses another hurdle. Many buyers do not prioritize whether the produce they purchase is organically grown, while others are skeptical about claims of chemical-free farming.

“This is why we hold a yearly regional organic congress to increase awareness about organic farming, which means working in harmony with nature, and for the consumers to know the benefits of chemical-free food,” he said.