Dying lands: Desertification taking another form in PH

MANILA, Philippines—Amid the various environmental challenges facing the Philippines, widespread land degradation poses a significant threat that could undermine the country’s agricultural productivity and food security.

Land degradation, as defined by the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), refers to the deterioration of land quality caused by human activities or natural phenomena.

This results in decreased productivity and usefulness of the land, which may involve vegetation loss, soil erosion, and depletion of soil fertility.

It has been noted that this environmental crisis could jeopardize the livelihood of millions and pose significant risks to the country’s ecosystems and overall health.

A global crisis

The UNCCD reported that globally, land degradation affects up to 40 percent of the planet’s land, directly impacting half of humanity and threatening half of the global gross domestic product (GDP), approximately $44 trillion.

Article continues after this advertisementREAD: Dying lands: Farmers fight to save the ‘skin of the Earth

Article continues after this advertisementThe latest UN data showed that between 2015 and 2019, at least 100 million hectares of healthy and productive land were degraded every year. This is equivalent to 4.2 million square kilometers, which is slightly over the combined area of five Central Asian nations: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan.

The yearly environmental decline caused by massive land degradation significantly affected global food and water security, directly impacting the lives of 1.3 billion people.

If current trends continue, the UN agency warned that an additional area almost the size of South America will be degraded by 2050.

Ibrahim Thiaw, executive secretary of the UNCCD, emphasized the urgent need for large-scale land restoration, calling it a powerful, cost-effective tool to combat desertification, soil erosion, and loss of agricultural production.

“Investing in large-scale land restoration is a powerful, cost-effective tool to combat desertification, soil erosion, and loss of agricultural production. As a finite resource and our most valuable natural asset, we cannot afford to continue taking land for granted,” Thiaw stated.

The UNCCD further stressed that around 1.5 billion hectares of land globally — roughly 150 times the size of the Philippines — must be restored by 2030 to achieve a land-degradation-neutral world.

Alarming PH situation

In the Philippines, the extent of land degradation is alarming.

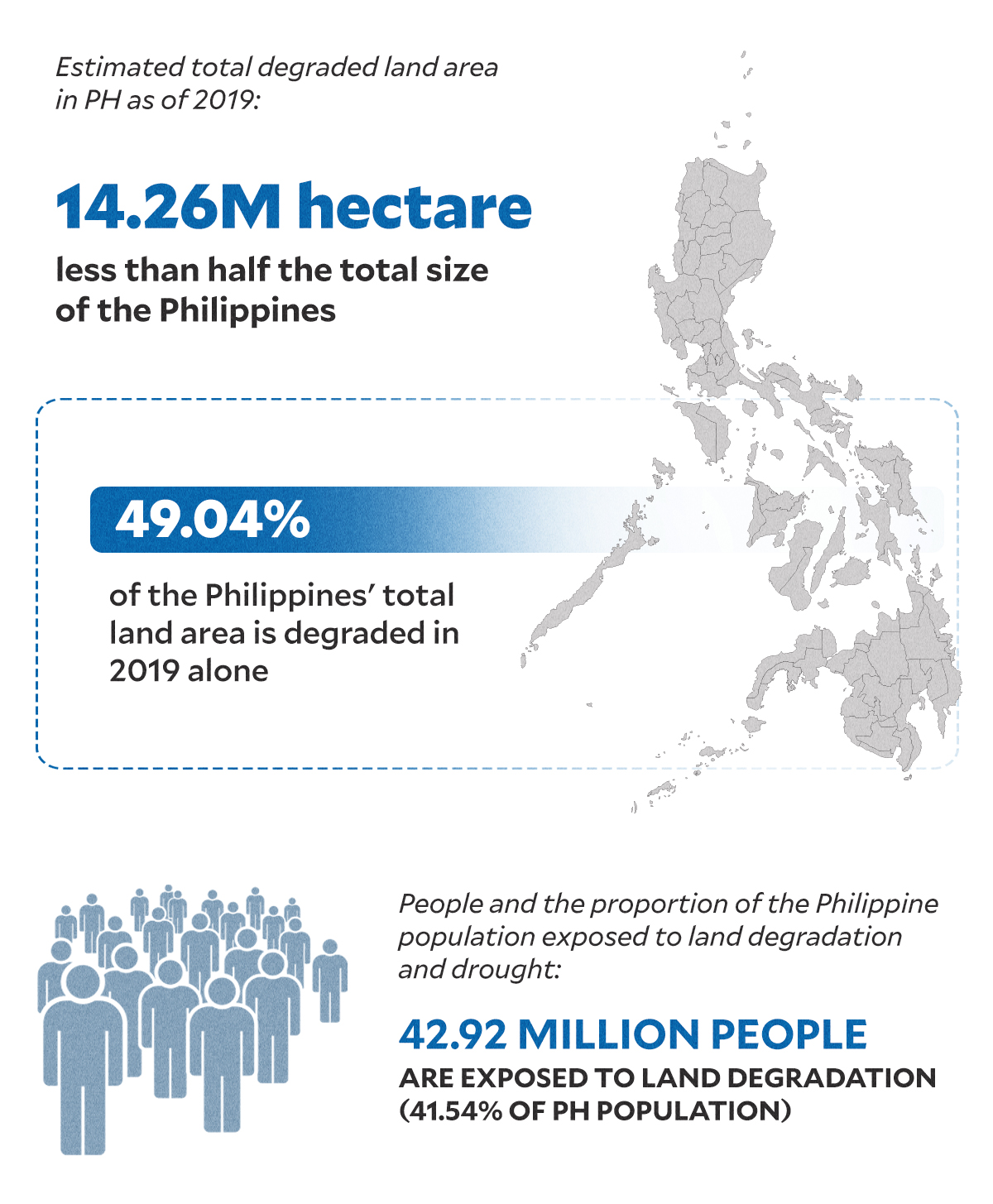

As of 2019, an estimated 14.26 million hectares of land is degraded, representing 49.04 percent of the country’s total land area. This is equivalent to the entire regions of Ilocos, Cagayan Valley, and Central Luzon combined.

According to the UNCCD and the Department of Agriculture (DA), this degradation affects nearly 42.92 million people, which is about 41.54 percent of the country’s population, exposing them to the adverse effects of land degradation and drought.

Among the primary drivers of land degradation in the Philippines are illegal logging, unsustainable agricultural practices, and conversion of forests into agricultural land.

The Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) has found that 75 percent of the country’s total cropland is vulnerable to erosion of varying degrees, leading to an annual loss of at least 457 million tons of soil for agriculture.

The DENR noted that the conversion of lands for settlements and the annual loss of approximately 47,000 hectares of forest significantly contribute to soil degradation.

It added that 11 to 13 million hectares of land across the country are classified as degraded, while 2.2 million hectares face low soil fertility due to improper fertilizer and pesticide use, leading to soil pollution and increased acidity, exacerbating the problem.

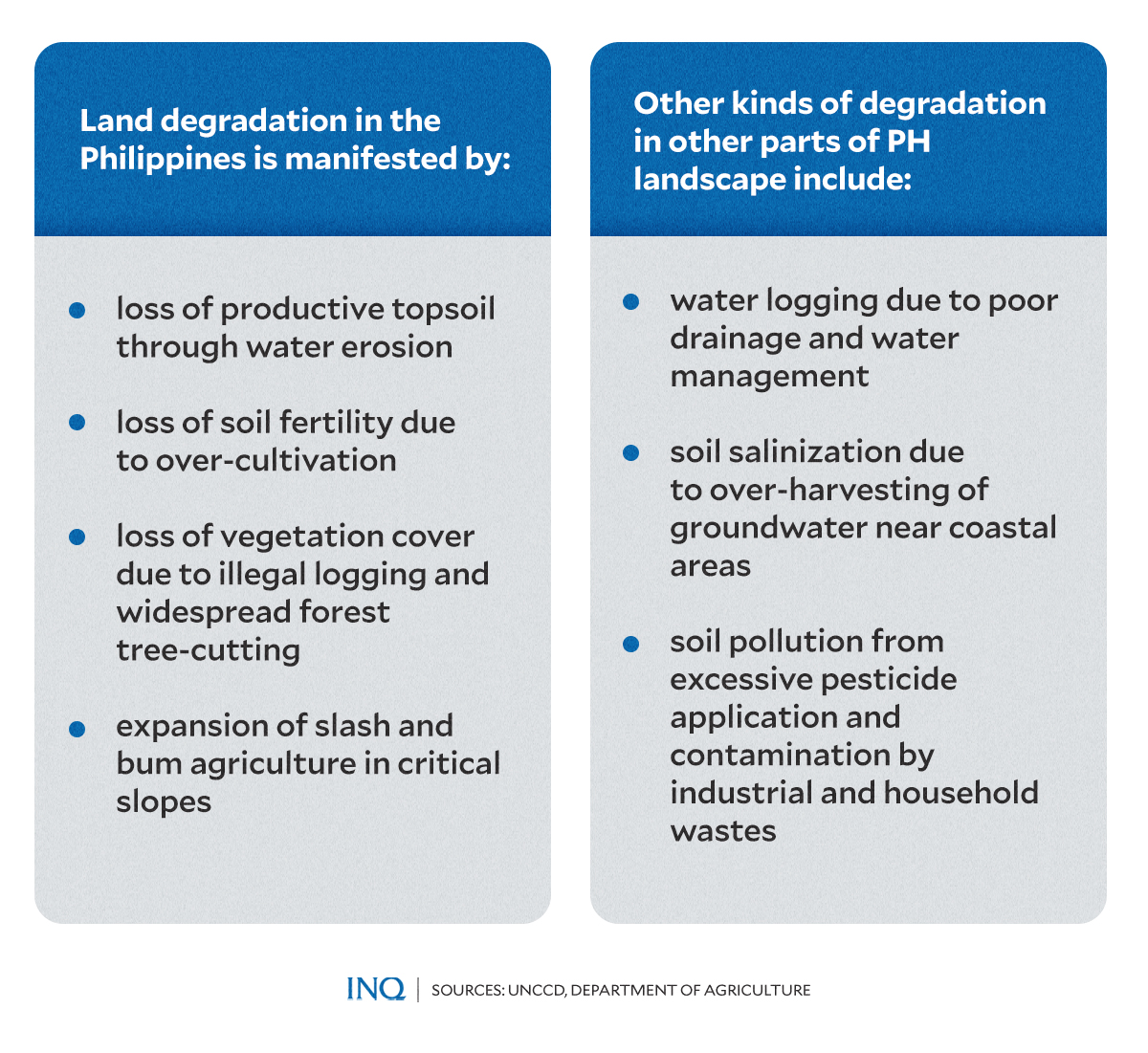

The Bureau of Soils and Water Management of the DA explained that the manifestations of land degradation in the Philippines include:

- Loss of productive topsoil through water erosion.

- Loss of soil fertility due to over-cultivation.

- Loss of vegetation cover due to illegal logging and widespread tree-cutting.

- Expansion of slash-and-burn agriculture on critical slopes.

Other forms of degradation impacting the Philippine landscape encompass water logging due to poor drainage, soil salinization from over-harvesting of groundwater near coastal areas, and soil pollution from excessive pesticide application and contamination by industrial and household wastes.

How does it affect us?

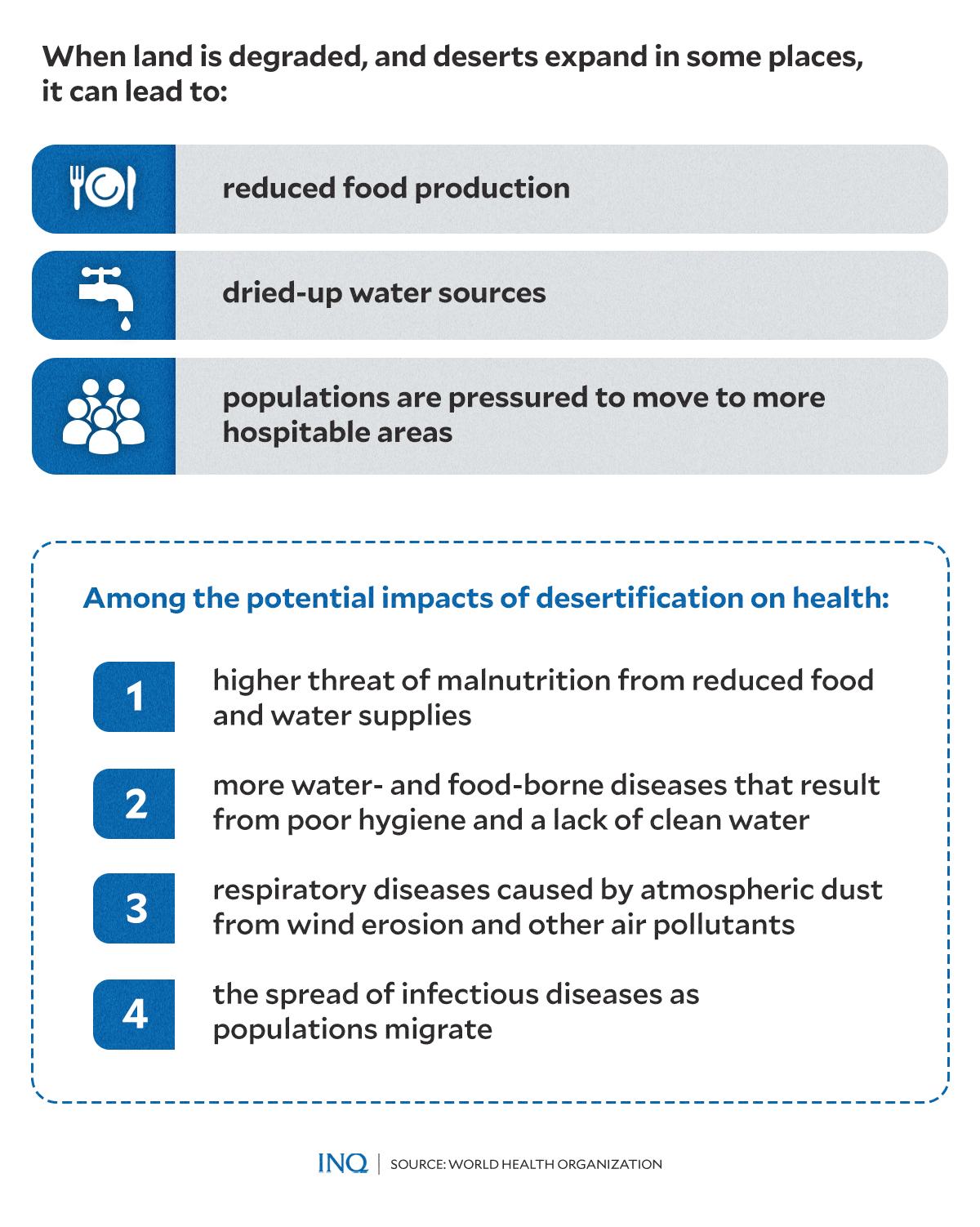

The effects of land degradation extend beyond the immediate loss of arable land. It reduces food production, depletes water sources, and forces populations to migrate to more hospitable areas.

The World Health Organization (WHO) stressed that among the potential impacts of land degradation and desertification on health include:

- higher threats of malnutrition from reduced food and water supplies

- more water- and food-borne diseases that result from poor hygiene and a lack of clean water

- respiratory diseases caused by atmospheric dust from wind erosion and other air pollutants

- the spread of infectious diseases as populations migrate

WHO added that as land is degraded and deserts expand in some places, food production declines, water sources dry up, and populations are pressured to relocate.

Desertification and heat

A specific type of land degradation, known as desertification, has been impacting various countries globally and is feared to affect the Philippines.

Desertification, according to UNCCD, is a specific type of land degradation that occurs in arid, semi-arid, and dry sub-humid areas, resulting from various factors, including climatic variations and human activities.

It transforms fertile land into desert-like conditions, significantly affecting ecosystems and human livelihoods.

Recent unprecedented high temperatures, with some areas experiencing extreme heat above 40 degrees Celsius in the first few months of 2024, have raised concerns. These conditions, studies showed, exacerbate the drying of soil and further aggravate degradation, impacting both agriculture and water resources critically.

Earlier this month, DA spokesperson Arnel De Mesa revealed that agricultural damage caused by El Niño has already reached P6.3 billion. The drought had affected 113,585 farmers and fishers in 12 of the country’s 17 regions, with the volume of production losses amounting to 255,467 metric tons in 104,402 hectares (ha) of agricultural land.

READ: El Niño damage to PH agri nears P6B

According to a 2023 study, the Philippines does not experience desertification in the typical dry land context. However, the country faces severe land degradation that compromises soil health and agricultural output.

Government promises

Last year, President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. vowed to take significant action to protect and rehabilitate the country’s threatened soils. He emphasized the need for modern agricultural practices and robust soil conservation measures.

Marcos then also served as the agriculture secretary.

“[O]ur soil is under threat, and to continue to neglect this vital agricultural component will lead to an even worse crisis in the future,” Marcos warned.

The President proposed a five-point agenda on soil and water management, which includes the National Soil Health Program and the implementation of sustainable land management.

“This will ensure the proper use and management of soil resources, address land degradation, enhance crop productivity, and, hence, improve farmers’ income,” he said.

READ: Bongbong Marcos on agriculture: ‘Our soil is under threat’

Marcos also said his administration is also investigating water security measures by implementing climate-resilient rainwater technologies and conducting cloud seeding operations.

He added that these initiatives aim to enhance water availability in agricultural production areas, critical watersheds, and reservoirs to mitigate the effects of the El Niño phenomenon.

Related stories:

Record PH heat drives power supply alerts, bares grid weaknesses

Spain worries over ‘lifeless land’ amid creeping desertification