Schistosomiasis, world’s 2nd worst parasitic disease, remains a threat in PH

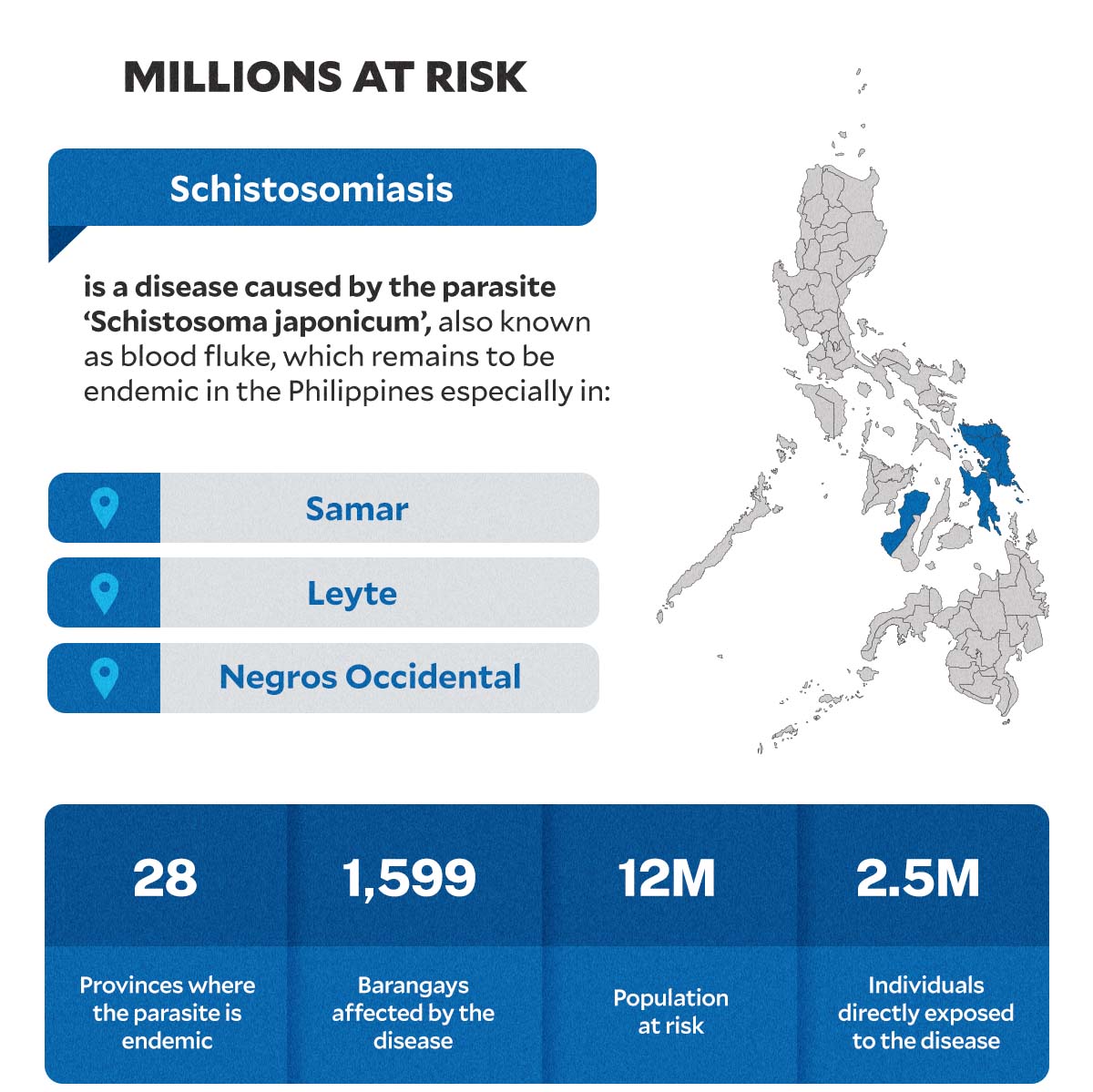

MANILA, Philippines—Still endemic, or unique, in almost 30 provinces, schistosomiasis, a parasitic disease, remains a serious public health problem in the Philippines with millions of people said to be at risk of infection.

This was the reason that every January, the Department of Health (DOH) is leading activities related to the Schistosomiasis Awareness and Mass Drug Administration Month with the vision of a “Schistosomiasis Free Philippines.”

According to its website, the DOH seeks to end the transmission of schistosomiasis infection by 2025 through “synchronized and harmonized” efforts from both public and private institutions.

RELATED STORY: Rare, deadly diseases in PH get attention from barely enforced law

It said by 2025, all high endemic barangays should reach the target criteria for “Morbidity/Infection Control” with just less than five percent prevalence of heavy intensity infection for five years.

Article continues after this advertisementLikewise, all moderate endemic barangays should reach the target criteria for “Transmission Control,” or the disease being eliminated as a public health problem, with just less than one percent prevalence of heavy intensity infection for five years.

Article continues after this advertisementLow endemic barangays should reach the target criteria for “Transmission Interruption” for five years. The DOH said this means “no local infection in man and animals” and “no infection in snails.”

This, as the DOH revealed that schistosomiasis is still present in 1,599 barangays in 189 municipalities and 15 cities in 28 endemic provinces across 12 regions, with some 12 million people considered at risk and 2.5 million individuals directly exposed to the disease.

READ: Philippines one of Asia’s ‘wormiest’ countries

According to the article “Prevalence and Distribution of Schistosomiasis in the Philippines: A Review,” which was published in the United States’ (US) National Library of Medicine, these are some of the provinces where schistosomiasis is endemic:

- Oriental Mindoro

- Sorsogon

- Northern Samar

- Eastern Samar

- Samar

- Leyte

- Bohol

- All provinces of Mindanao, except Misamis Oriental, Davao Oriental, and Maguindanao

But the National Nutrition Council (NCC) said schistosomiasis, which is considered by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as one of the most neglected tropical diseases in the world, is also endemic in Negros Occidental and Cagayan.

RELATED STORY: ‘Neglected’ diseases discussed

2nd worst parasitic disease

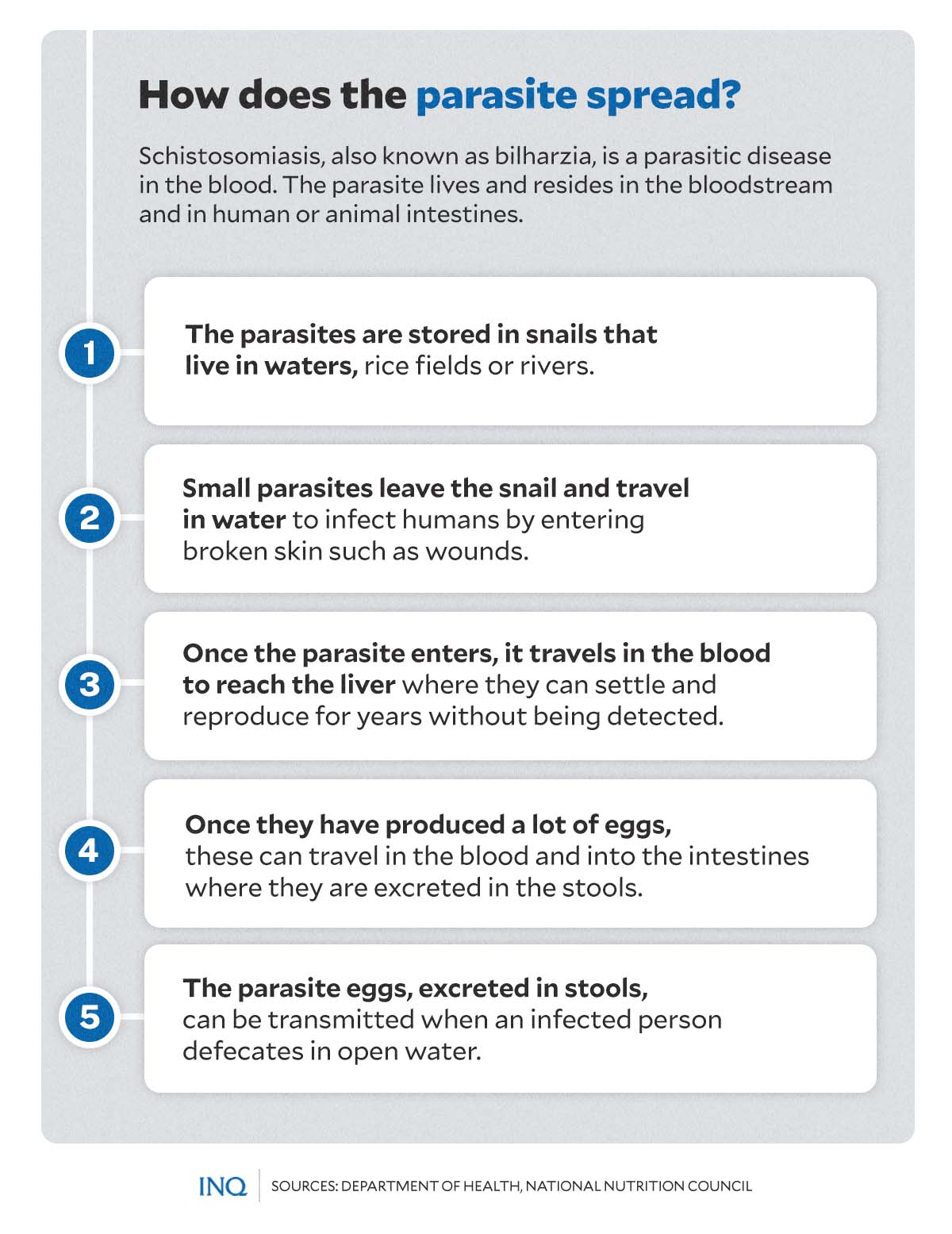

The NCC said schistosomiasis is an acute and chronic disease caused by the parasite Schistosoma japonicum, also known as the blood fluke, or trematode worm, that “lives and resides in the bloodstream.”

It explained that the parasites are stored in snails that live in waters, rice fields or rivers. The worms leave the snail and travel in water to infect humans, and even domestic animals, by entering openings in the skin, like wounds.

RELATED STORY: Schistosomiasis grips villages in Leyte town

“Infection occurs when your skin comes in contact with contaminated fresh water in which certain types of snails that carry schistosomes are living,” the DOH stated in an article regarding the disease.

It said freshwater becomes contaminated by the parasite when infected people openly defecate in fresh bodies of water or in the environment near these bodies of water. The eggs hatch, and if snails are present, the parasites develop and multiply inside until it becomes “cercaria”.

Once the parasite enters human or animal bodies, it travels in the blood to reach the liver where they can settle and reproduce for years without being detected. Once they have produced eggs, the eggs can travel in the blood and into the intestines where they are excreted in the stools.

The NCC said this means Schistosoma japonicum is spread when an infected person defecates in open water. The parasites can penetrate the skin of persons who are wading, swimming, bathing, or washing in these waters.

As stressed by the US CDC, when it comes to impact, schistosomiasis is second to malaria—a serious and sometimes deadly disease caused by a parasite that infects a certain type of mosquito—as the most devastating parasitic disease.

RELATED STORY: Raising awareness about rare diseases nationwide

According to data from World Health Organization (WHO), some 236.6 million people all over the world required preventive treatment in 2019, with 78 countries being able to report schistosomiasis transmission.

What happens if one gets infected?

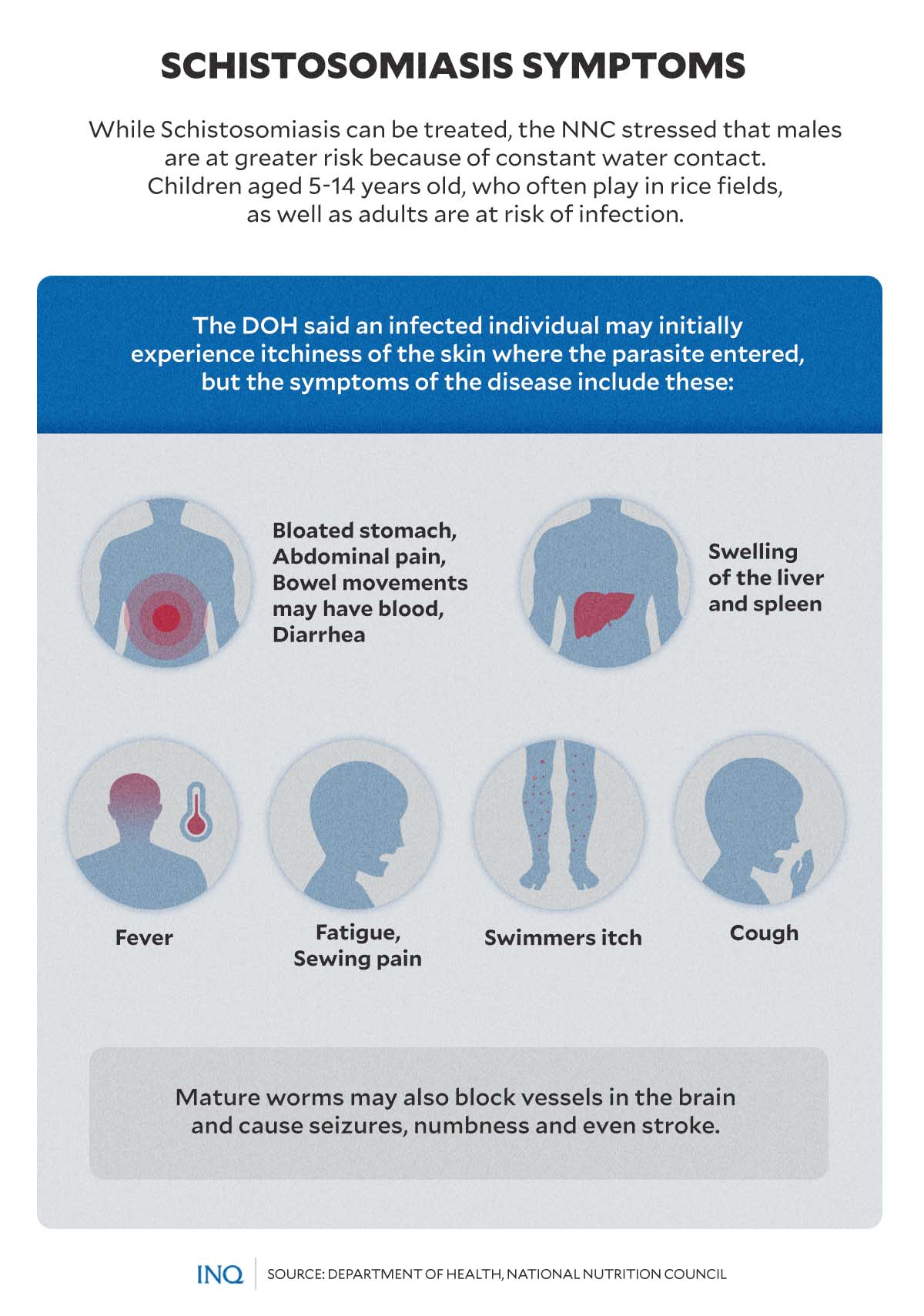

The risk of infection is higher for individuals living in endemic provinces, especially in Mindanao. Males have greater risk because of constant contact with water, while children (5 to 14 years old) who often play in rice fields, as well as adults, are also at risk of getting infected.

As stated by the US CDC, symptoms of schistosomiasis are caused not by the worms themselves but by the body’s reaction to the eggs: “Eggs shed by the adult worms that do not pass out of the body can become lodged in the intestine or bladder, causing inflammation or scarring.”

The NCC said in the early stage of infection, an individual may experience itchiness of the skin where the parasites entered, fever, abdominal pain and diarrhea. Then the infected person will start to have katayama or “snail fever.”

When one has snail fever, he or she experiences a tendency to get tired, respiratory symptoms such as coughing, joint pains, muscle pains and fever. The DOH said symptoms also include a bloated stomach and blood in the stool.

The US CDC explained that “most people have no symptoms when they are first infected, however, within days after becoming infected, they may develop a rash or itchy skin [then] within one to two months of infection, symptoms may develop.”

As the infection progresses, the parasites may damage the liver leading to enlargement of the abdomen as seen in infected children. The worms may also affect blood circulation in the lungs which may cause wheezing and coughing.

The NCC said mature worms may also block vessels in the brain and cause seizures, numbness and even stroke. While it is not immediately deadly, the Medical News Today stressed that schistosomiasis is a chronic illness that can “seriously damage the internal organs.”

Without treatment, the disease can persist for years, the US CDC said. Symptoms of chronic schistosomiasis include abdominal pain, enlarged liver, and blood in the stool or blood in the urine. Chronic infection can also lead to increased risk of liver fibrosis or bladder cancer.

Schistosomiasis can be treated

But there is a “safe and effective” medication available for treatment of the disease.

“Schistosomiasis is treated with anti-parasitic medication such as Praziquantel which is considered safe and highly effective in single or divided doses against the Schistosome parasite,” the NCC said.

However, there are side effects because of the reaction of dying worms like abdominal pain or discomfort, nausea, decreased appetite, dizziness, headache and fever but they are only mild and transient.

WHO said schistosomiasis control focuses on reducing the disease through periodic, large-scale population treatment with Praziquantel. Even though re-infection may occur after treatment, the risk of developing severe disease is diminished.

The groups targeted for treatment are:

- Preschool children

- School-age children in endemic areas

- Adults considered to be at risk in endemic areas, and people with occupations involving contact with infested water, like fishermen, farmers, irrigation workers, and women whose domestic tasks bring them in contact with infested water

- Entire communities living in highly endemic areas

WHO recommends treatment of preschool children since there is no suitable formulation of Praziquantel to include them in large-scale treatment programs. A pediatric formulation of the medicine is being developed.

Preventable

But while schistosomiasis can be treated, a more comprehensive approach against the disease should include the provision of potable water and adequate sanitation. Snail control would also reduce transmission.

This, as the WHO stressed that the disease is prevalent in tropical and subtropical areas, especially in poor communities where there is no access to safe drinking water and adequate sanitation.

“Schistosomiasis mostly affects poor and rural communities, particularly agricultural and fishing populations. Women doing domestic chores in infested water, such as washing clothes, are also at risk and can develop female genital schistosomiasis,” it said.

The NCC said to make the fight against schistosomiasis sustainable, health education and investment in clean water supply and sanitation, environmental and snail control need to be a part of the overall strategy.

It shared these tips to prevent schistosomiasis transmission:

- Take anti-parasitic medications such as Praziquatel when living or traveling to endemic areas.

- Wear protective boots when walking in watery puddles or rice fields. Treat wounds as soon as possible and prevent contact with rivers or rice fields.

- Drain the breeding sites of snails through proper management of irrigation systems, removal of shade and shelter from the sun by clearing vegetation.

- Prevent snail breeding on the banks of streams or irrigation canals by lining these with concrete or making them more perpendicular.

- Accelerate the flow of water by proper grading and cleaning of the stream bed and removal of debris.

- Cover snail habitats with landfills.

- Do not defecate in the open.

- Maintain a healthy body through good nutrition to reduce the risk for infections including parasitic infections.

RELATED STORY: Public health stakeholders urge gov’t to sustain Rare Disease Act