Buddy Gomez: Waray warrior who defended democracy

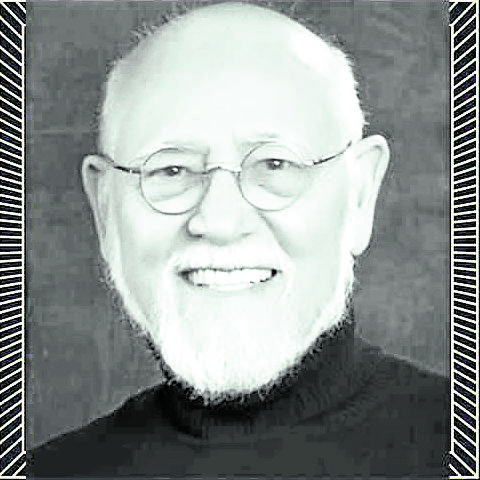

Tomas “Buddy” Gomez III —OFFICIAL BUDDY GOMEZ FACEBOOK

ACCOUNT

LOS ANGELES — History’s ebb and flow were again on full display on July 26 in my homeland the Philippines as President Rodrigo Duterte nearly lulled the nation to sleep with his long and winding State of the Nation Address that stretched to eternity and back.

But before the day ended, Filipinos everywhere sprang to their feet as weightlifter Hidilyn Diaz gloriously grabbed the country’s first ever Olympic gold in Tokyo, Japan, lifting her nation’s spirits in an otherwise dreary day.

As the nation’s mood swung from disappointment to euphoria that evening, I found myself in mourning because an old friend and kababayan of mine, and one of the country’s staunch defenders of democracy, Tomas “Buddy” Gomez III, had died.

The sad news filtered from the internet that the former press secretary of President Corazon “Cory” Aquino succumbed to a heart attack on July 22 while on a personal pilgrimage along the famous Camino de Santiago road to Galicia, Spain.

To the democratic faithful, Gomez’s death at age 86 came at a time when the country was still in mourning from the death on June 24 of former President Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino III.

Article continues after this advertisement“Mano Buddy,” I called him. That honorific is not only because he was older than me by about 28 years; we also came from the same region in Eastern Visayas (he was from Samar and I, from Palo, Leyte) where respect for the elderly is still part of the social norm.

Article continues after this advertisementBecause of this common bond, we learned to respect each other’s professional boundaries; that dicey place and sometimes, complicated space, that exists between journalists and their sources of news.

Never red-tagged

Thirty years ago, this brief but valuable friendship started on a sour note when the Inquirer assigned me to report from Malacañang, pinch-hitting for my eminent colleague Nimfa Rueda. But my past stories about forest plunder, government corruption and poverty in the Leyte and Samar islands were displeasing Malacañang.

Moreover, Gomez was part of the privileged elite in Samar that my stories were railing against.

But Gomez never red-tagged my reporting as “fake news,” as the current Malacañang spokesperson is wont to do. Instead the Calbayog native saw a silver lining to use the levers of presidential power to address the social inequity in his long, neglected home province.

Years later, Gomez would tell me that because of my reporting that year, the Aquino administration—and several foreign governments—ended up pouring a lot of development funds to the three Samar provinces.

“Mapupusil ka Idoy! (You will get yourself killed!),” the loyal San Beda sidekick and acolyte to the martyred Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr. warned me in Waray in December of 1991, as I and members of my family started receiving death threats for my reporting in Samar.

Seven months earlier, he helped me navigate my first visit to the United States when he wrote a letter that introduced me to Ambassador Emmanuel Pelaez in Washington.

A letter, a dream

I am sharing this letter to the Inquirer — and the public — for the first time in the Philippines. The only other time I showed this letter to anybody was in 2001, when I successfully defended my petition for political asylum at the immigration and naturalization service in Anaheim, California.

That letter showed his plan to run for the senate in 1992. A race that he lost miserably—together with 22 other candidates backed by the lame-duck Cory Aquino in that election that elevated Fidel Ramos to the presidency. That loss was hard on him as it dashed his dream of following in the footsteps of his grandfather and namesake, the late Samar Sen. Tomas Gomez.

“I am very proud to be a Waray-Waray hometown boy,” he would say countless times when visiting his native Calbayog.

Even from his retirement haven in San Antonio, Texas, Calbayog was always in his mind, whether he was promoting his hometown’s cacao, the tinapa or his favorite humba, or expressing outrage in his blog (“Cyberbuddy”) at the spate of political assassinations that killed two Calbayog City mayors in a span of 10 years.

Gifted with an eloquence that matched his zest for life, Gomez later became the truth-telling crusader that fought valiantly against the forces that want to erase a nation’s collective memory.

Cory’s eyes and ears

To honor my departed kababayan, I joined the novena on Zoom Tuesday morning (Tuesday night, July 27, in Manila) hosted by his daughter Karen Gomez Dumpit, the deputy commissioner for human rights.

“Buddy was never boss-like. He treated us all as his equal,” said Lourdes Siytangco, in the same novena held in memory of her boss who replaced Adolfo Azcuna in January 1990.

As consul general in Hawaii from 1986 to 1989, Gomez will probably be remembered for keeping the exiled former dictator Ferdinand E. Marcos and his wife former First Lady Imelda Marcos from destabilizing the Aquino government.

“In the guise of consul, he was Tita Cory’s eyes and ears,” said Azcuna, who also attended the same Zoom novena.

“Guard dog gad la ako (I was only a guard dog),” Gomez told me in 1991, his self-deprecating description of himself showing a hint of undisguised braggadocio.

“He (Gomez) was the plague in our lives whose chief preoccupation was to keep track of our doings,” Arturo Aruiza, the dictator’s chief confidant, wrote in his 1991 book “Malacañang to Makiki.”

But the hunter and the hunted, the two Waray protagonists in this real-life drama—democracy’s vital cog from Calbayog and the tenacious Rose of Tacloban—shared the same human stain that has afflicted the Catholic Church for centuries.

Gomez and Mrs. Marcos are both descended from Spanish friars, their grandfathers both Franciscan priests. Exactly the Padre Damaso character that Jose Rizal continues to warn us—to this day—in his eternal “Noli Mi Tangere.”

When he became a father again at age 52, he named his son Jose Maria Sebastian Gomez, after the Franciscan friar from La Huerce, Spain, that started their bloodline in Calbayog.

On the Camino de Santiago, that road in Spain where sinners have walked for centuries seeking communion with God, he may have thought about that Spanish priest and the son that now carries his name.

Was sin and redemption on his mind when he died under Iberian skies on July 22? That fateful date was the feast of Mary Magdalene.