Starting a new year of life in the middle of a global pandemic

My birthday dinner was, in a way, a kind of Last Supper.

It was the final night of a trip I had taken to a country thousands of kilometers away from Manila, which was under a de facto lockdown. I had left a week earlier amid a veneer of relative calm, the full scale of the local transmission of the new coronavirus disease (COVID-19) only just coming into focus.

But each day since then brought a torrent of bad news. It was a rapid-fire crystallization of a crisis that had unfolded for months in Wuhan, China; Daegu, South Korea; Bergamo, Italy — places that had felt distant enough for us to have the luxury of abstraction.

The trip afforded me a weeklong extension of that suspended reality. Though the country I was visiting had itself been dealing with a slew of confirmed cases, it was a first-world nation that seemed to have everything under control.

At the very least, the atmosphere was one of uninterrupted normalcy.

But loved ones at home made me hyperaware that I would not be returning to the same Manila I left. The streets that only days earlier were crawling with traffic on my way to the airport had now emptied. Checkpoints had been erected, guarded by gun-wielding military troops.

It was this new reality that I prepared to enter on the night of my birthday, the eve of our flight back. We dined in a low-lit tapas bar at the heart of the city’s arts district. It was a celebration with an undercurrent of loss, an anticipatory nostalgia for what I knew would be my last “normal” night.

Person under monitoring

I touched down in Manila 18 hours later on a flight with more vacant seats than passengers. I was home, but also a person under monitoring set to start a 14-day quarantine. The eerie, unoccupied expanse visible from the taxi window could have just as easily been any other city.

While the quarantine has been an adjustment, I am privileged to even have a home to hunker down in. In many ways, I still feel like I’m watching the threat of COVID-19 from afar, even as it has crept into ever more intimate spaces—friends of friends, former classmates, neighbors.

This feeling is amplified by my job as a journalist. I had been trained to operate under the ethos that the worse things got, the more necessary it was for us to hit the pavement. But my days are instead spent calling sources, parsing the internet and getting reacquainted with instant coffee.

It is an almost unnerving feeling—covering the worst health and economic crisis of our time mostly from within the perimeter of my bed.

And while reporters have long been forced to resort to creative means to chase down a story, there is a value to human interaction that cannot be replicated. It is one thing to write about the fraying of our social fabric. It is another to look a fatigued doctor—or lying politician—in the eyes.

But this is not a feeling unique to journalists. The cruelty of the virus is in how it has forced isolation at a time when what we really need is solidarity. There is the obvious tragedy of death, but there is also the tragedy of an ever-expanding constellation of missed connections.

In journalism as in life, these connections are our real currency.

New normal

Particularly in a time like this, with the frailty of our existing systems exposed and ruling class interests threatening our survival, those missed interactions cross from the personal into the threshold of the political. How do we demand accountability when we cannot organize?It starts, I suppose, with recognizing that there will be no return to normal. And more importantly, taking the immediate steps to ensure we and those we love can get there.

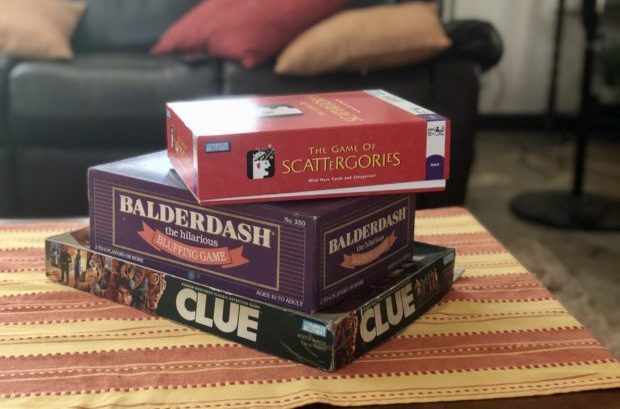

I am fortunate to be in quarantine in the same household as my immediate family. We eat all our meals together, something that was exceedingly rare prelockdown. We play board games almost nightly. Our dusty badminton net has made a reappearance in our backyard.

These activities, however fleeting, help to distract from mounting worries. My father is a doctor, and while his line of specialty is not related to medical emergencies, there is a rising possibility that he could be called to volunteer as hospitals buckle under the weight of more cases.

Infuriatingly personal

My grandfather, who is in his mid-80s, just recently recovered from a respiratory illness. It is the thought of my grandparents that makes the actions of those like Sen. Aquilino “Koko” Pimentel III feel infuriatingly personal. It kills me to not be able to spend time with them.

Though I am now at the final stretch of home quarantine, it is anyone’s guess how many more weeks or months the lockdown could last. But even as we are sheltered, we cannot afford to let ourselves be paralyzed.

I never imagined spending the first weeks of a new year of life under quarantine, though writers have long had an irrational infatuation with resignation. Think Henry David Thoreau, who famously self-isolated in the woods because he wished to “live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life.”

He was not, however, living through a global pandemic. Now more than ever, we must lean on the most essential thing we have — each other.

Editor’s Note: The writer has asked for anonymity for safety reasons.

For more news about the novel coronavirus click here.

What you need to know about Coronavirus.

For more information on COVID-19, call the DOH Hotline: (02) 86517800 local 1149/1150.

The Inquirer Foundation supports our healthcare frontliners and is still accepting cash donations to be deposited at Banco de Oro (BDO) current account #007960018860 or donate through PayMaya using this link.