The secret life of pangolins

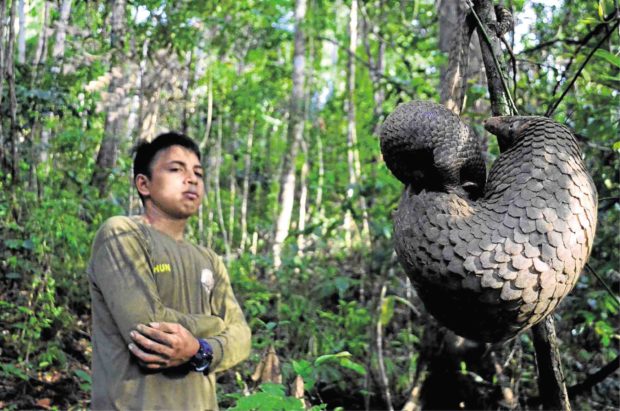

RUSH TO SAFETY A pangolin and its young look for shelter in the wilds of Southern Palawan. —PHOTOS BY GREGG YAN

PALAWAN, Philippines — It’s 1 a.m. and deep in the jungles of Palawan, researchers and a squad of Philippine Marines are searching for pangolins, the most illegally trafficked mammals on earth.

Pushing up a sheer slope of thorny rattan palms carpeted with rotting orange leaves, our Tagbanua scout Joel’s tracker dog Itiman suddenly barks, picking up a scent. “We haven’t found a pangolin in six months,” Joel confessed a day before.

But there are fresh pangolin claw marks on the trees around us. The three Marines behind me lock and load M4s in case what Itiman found isn’t a pangolin. We slink forward.

Pangolins, or scaly anteaters, got their name from Malaysians, who called them “penggulung” (“parang gulong” in Filipino — like a tire) for their tendency to roll into protective balls when threatened.

Their golden scales that look like King’s guard armor from “Game of Thrones” shield them from predators and prey. They use backhoe-like claws and sticky tongues to rip into and slurp up to 20,000 ants or termites nightly, the main reason they’re incredibly hard to keep in captivity.

Article continues after this advertisementFour species inhabit Africa while four more live in Asia, including the Philippine pangolin (Manis culionensis), found only in the province of Palawan and classified as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Article continues after this advertisementHaving developed secretive habits to avoid detection and predation, pangolins hide in earthen burrows, rotting tree stumps, or high in trees, emerging only at night. They give birth to one or two young yearly—less than the current rate of capture for the illegal wildlife trade.

“They’re what we call cryptic animals, experts at remaining hidden,” says Phoebe Meagher of Australia’s Taronga Zoo, who joined the research team.

The US Agency for International Development (USAID)’s Protect Wildlife Project is working closely with the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development and Katala Foundation to assess pangolin numbers in mainland Palawan.

“This initiative aims to give decision-makers an idea of just how many pangolins remain in the Philippines,” says Sabine Schoppe, an expert on the Philippine pangolin. “With their range limited to the islands of Palawan, we need to conserve these animals before they’re hunted to extinction.”

Meat and scales

An estimated one million pangolins have been traded in at least 67 countries in the past decade to feed the centuries-old demand for meat and scales — especially in China and Vietnam, the top consumers. The meat is a delicacy; the scales are used as traditional medicine.

Due largely to poaching, the population of the Philippine pangolin has dropped by 95 percent since the 1980s, the Chinese pangolin by 94 percent since the 1960s, and the Sunda pangolin by 80 percent since 2000.

“The traditional Chinese medicine trade has already wrought havoc on Asian pangolin populations, so the trade has shifted to Africa. Since Asian pangolins are now rarer, they fetch higher prices,” Schoppe says.

At least 667 poached Philippine pangolins were intercepted by authorities from 2001 to 2017. In April 2013, a Chinese poaching vessel rammed into the Philippines’ famed Tubbataha Reef. Found aboard were 2,870 dressed Sunda pangolins, which were eventually buried in Puerto Princesa.

In April 2019, 25 tons of scales from an estimated 38,000 African pangolins were confiscated in Singapore—the largest haul ever recorded. Just four months earlier in January, nine tons of scales from an estimated 14,000 pangolins were intercepted in Hong Kong. In 2007-2009, Malaysia’s Sabah Wildlife Department revealed just one syndicate traded 22,200 dead and dressed pangolins.

The poaching goes on even while all pangolin species are banned from international trade under the multilateral treaty, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora.

Traditional Chinese healers believe that pangolin scales — made of keratin, like human hair and nails—have magical powers. They believe that the scales, which are dried, ground and inserted into pills, relieve fever, pain, ulcers, arthritis and other ailments.

A 1938 article in Nature stated: “The scales—when roasted, cooked in oil, butter, vinegar, boy’s urine or other substances—can cure various conditions, including hysterical crying in children, malarial fever, deafness, plus women possessed by ogres or devils.”

These claims have zero basis in science, but convincing millions of users to shift to alternatives hasn’t proven easy.

Trade driver

Stopping the trade starts with reducing demand for pangolin meat and scales. The meat is often a status symbol, for it doesn’t actually taste good. The scales drive the trade.

“Think about it. No one pays for powdered fingernails, but traditional Chinese medicine believers spend a fortune for powdered pangolin scales, which are no different,” Schoppe says. “Legal prescribed medicines are cheaper and more efficient alternatives, while the alleged powers of pangolin scales will die out with the last pangolin. It’s time to leave old traditions behind and opt for more sustainable solutions.”

Western and Chinese medicine experts have found that cowherb seeds, earthworms and other items are viable alternatives to pangolin scales. Tighter enforcement of laws is needed.

“Wildlife trafficking doesn’t rank as highly in the government’s radar as drugs or weapons trafficking,” notes Edward Lorenzo, USAID’s Protect Wildlife crime prevention advisor. “The illegal wildlife trade is run by organized syndicates with their own systems for capturing and smuggling animals, pangolins included. Since we’re an archipelago, it’s also hard to monitor exit and entry points, especially informal ones. Boats can land anywhere and smuggle out wildlife.”

Last June, 10 live pangolins were seized at a checkpoint in Tagaytay City.

Regional collaboration is crucial. “DNA tests conducted for the pangolins confiscated off the Tubbataha Reef in 2013 revealed they came not just from Palawan, but also from Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia and Vietnam. This is significant for it proves that illegal traders source their contraband from all over Southeast Asia,” says Mundita Lim, executive director of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) Center for Biodiversity.

She adds: “Efforts to combat the illegal wildlife trade cannot be undertaken separately, at a country-by-country level, but through coordinated action at the regional level. An Asean ministerial declaration adopted in Chiang Mai in early 2019 outlined the commitment of Asean member states to combat the illegal wildlife trade individually and regionally. China, the biggest consumer, should be engaged through the Asean plus China framework for cooperation.”

Sheer stupidity

We actually find two pangolins, one a juvenile. Researcher JR Pastraña swiftly puts the pair in a canvas bag while Elmie Caabay jots down GPS coordinates, food sources and so on.

At our jungle base camp hours later, JR and Elmie take measurements and fecal and scale samples before marking the animals with white water-based paint to ensure they won’t be counted twice if seen again. In 10 months, the research team had covered 2,000 hectares, encountering just 16 pangolins.

After a few minutes at base camp, we trek back up the mountains to release our rare finds.

The sheer volume, the sheer stupidity, of the global trade in pangolins struck me hard because I’ve seen how difficult it was to find even one of them. I realized how even the most lovable, harmless animals can disappear because of human greed. But beside me, the young researchers were full of hope.

Perhaps, with no-nonsense enforcement measures in source countries like the Philippines, plus an aggressive campaign to cut demand in consumer countries like China and Vietnam, pangolins might have a slim chance of making it to the next century. But if the trade continues, as it has the past decades, then pangolins had better hide—for their own good.

May they live long, safe and secret lives!