Meet ‘MakMak’: Kiddie campaign conveys grave state of Philippine wildlife

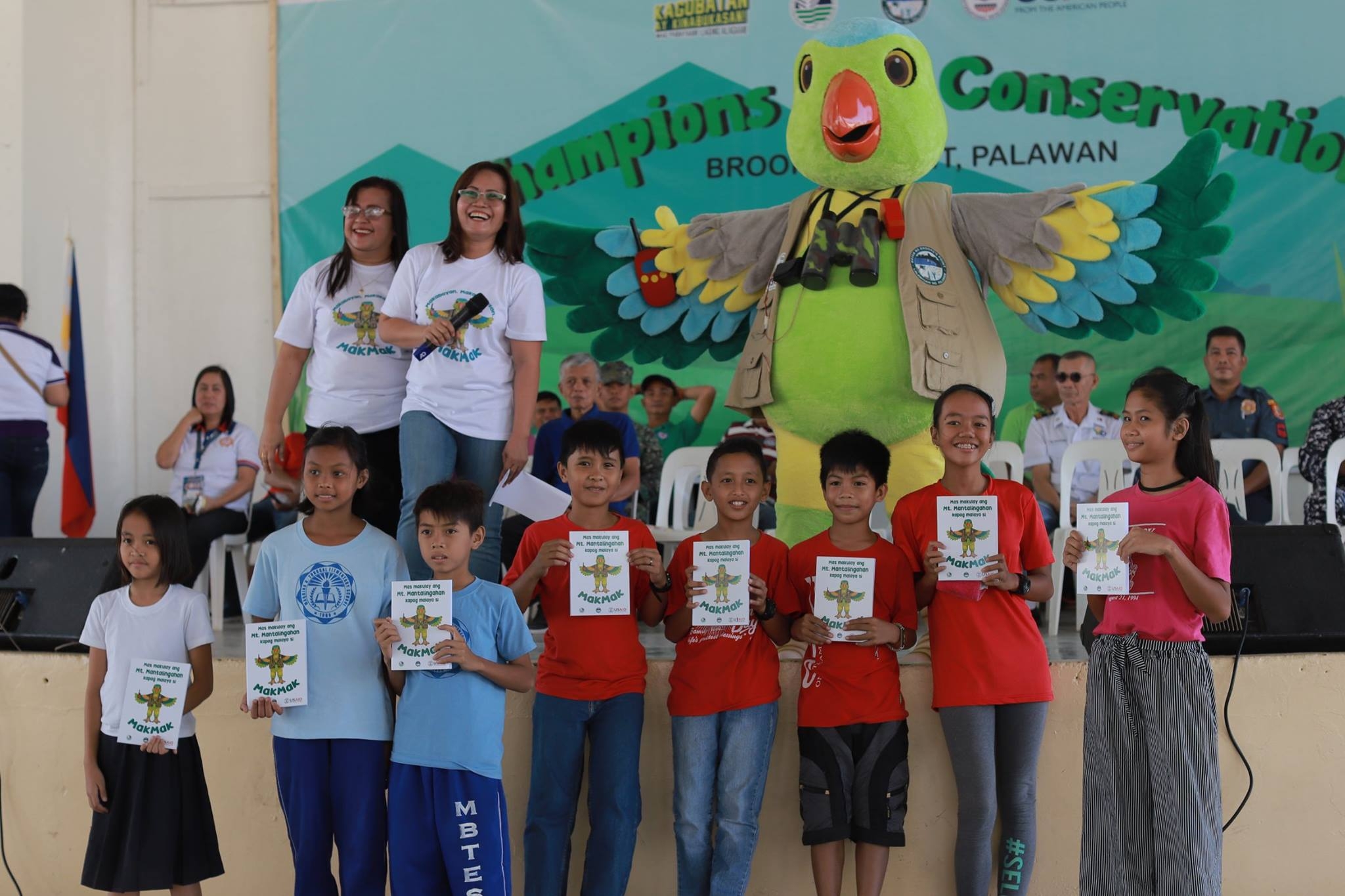

OFF TO A FLYING START MakMak, a mascot depicting the nearthreatened blue-naped parrot endemic in Brooke’s Point, Palawan,

leads the launch in March of a campaign against illegal wildlife trade. MakMak is expected to land and roost in different schools

this coming school year. —PHOTO COURTESY OF USAID PROTECT WILDLIFE

PUERTO PRINCESA CITY — Clad in a brown ranger vest, “MakMak” will soon fly in and make a clarion call for biodiversity conservation in schools at Brooke’s Point town in southern Palawan.

But MakMak, with his radio, binoculars and whistle, is no ordinary ranger.

Rather, he is a mascot of the endemic blue-naped parrot (Tanygnathus lucionensis), which has been drafted as the town’s ally against the illegal wildlife trade.

MakMak, which stands for “makabayan, makakalikasan,” is the brainchild of local officials who underwent the “Campaigning for Conservation” training under Protect Wildlife, a project by the US Agency for International Development (USAID) for biodiversity conservation and habitat protection.

Launched in March, MakMak was an idea designed to develop a love for nature in the hearts of children through puppet shows, comics and songs.

Article continues after this advertisement“We believe that children have an influence on their parents,” said Rebecca Gadayan, acting municipal information officer.

Article continues after this advertisement“We want them to tell stories to their parents about how they should join in forest protection efforts to protect MakMak’s kind and other species thriving in the forest.”

Face of campaign

Local officials said they chose the colorful bird to be the face of the town’s environmental campaign since it was easier to elicit empathy for the bird that was already popular in communities.

Brooke’s Point is one of five municipalities in Palawan covered by the Mt. Mantalingahan Protected Landscape, an area of 120,457 hectares that is home to indigenous peoples as well as several endemic and endangered flora and fauna.

It is also the point of origin of Brooke’s Point’s watershed, which provides water to the mainly agricultural town.

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), there are four critically endangered, five endangered and 14 vulnerable species within this protected area whose forests also host threatened and restricted-range birds of the Palawan Endemic Bird Area, including the blue-naped parrot.

Uphill battle

But the illegal wildlife trade and improper use of some of the town’s natural resources, like timber, have threatened its rich biodiversity.

Despite multiple efforts by the local government to push environment protection and conservation among adults, it remains an uphill battle, Gadayan said.

“We’ve had so many environmental campaigns targeting adults, but they have not been truly effective,” she said, adding that wildlife capture and poaching, as well as kaingin, or slash-and-burn practices, remain.

“So this time, we decided to flip our strategy: it will be the children who will now influence their elders. They can share with their parents our message that MakMak should remain free and his habitat should be protected.”

Locally known as “pikoy,” the blue-naped parrot, or the Philippine green parrot, is listed as a near-threatened species in the IUCN’s Red List, with its population on steady decline because of hunting, trapping and habitat loss.

School partnerships

As of last year, the IUCN said that there are some 1,500 to 7,000 mature pikoy in the wild.

Gadayan said local officials hope to roll out their campaign in school events, partnering with teachers and school administrators to include their message of conservation in the academic year’s activities. They hope to visit at least one or two schools every month.

Outreach activities in the town’s 18 barangays are also being eyed for MakMak, which has already received positive feedback during the campaign’s official launch with schoolchildren earlier this year.

Renewed strategy

While the USAID has underwritten the conceptualization and execution of the campaign with a P300,000 funding, the local government of Brooke’s Point has also committed P200,000 to continue implementing the campaign throughout the year.

But it remains to be seen whether MakMak and the renewed campaign strategy will bring about behavioral and cultural change in how communities and indigenous groups protect the environment, Gadayan said.

“We know there is still a long way to go,” she said. “What is important is to continue our efforts and spread our campaign to keep MakMak and other species free to roam in their habitat.”