Study profile of drug war fatality: male, poor, killed in ‘shootout’

A CANDLE FOR EVERY KILLING This art installation at Ateneo de Manila University’s George SK Ty Learning Innovation Wing of the Areté shows that there are as many candles as there are deaths in the Duterte administration’s bloody war on drugs. —NIÑO JESUS ORBETA

Five months after President Duterte launched a brutal war on drugs in 2016, Ronaldo Morales, a garbage hauler, was killed during a police operation in Quezon City.

But the 46-year-old father of three was not the target of the buy-bust operation carried out by narcotics agents from the Batasan Hills station of the Quezon City Police District.

The target was a man known as “Jerry Tattoo,” who was later identified as Jerry Baldosa, his brother-in-law who also hauled trash and lived next door.

The police, however, described Morales as a “cohort” who was with Baldosa on the evening of Dec. 6, 2016, at Barangay Bagong Silangan.

The police report said that during the operation, the two “sensed the presence” of cops and fired at the officers, who returned fire, killing both men.

Article continues after this advertisementAteneo-De La Salle study

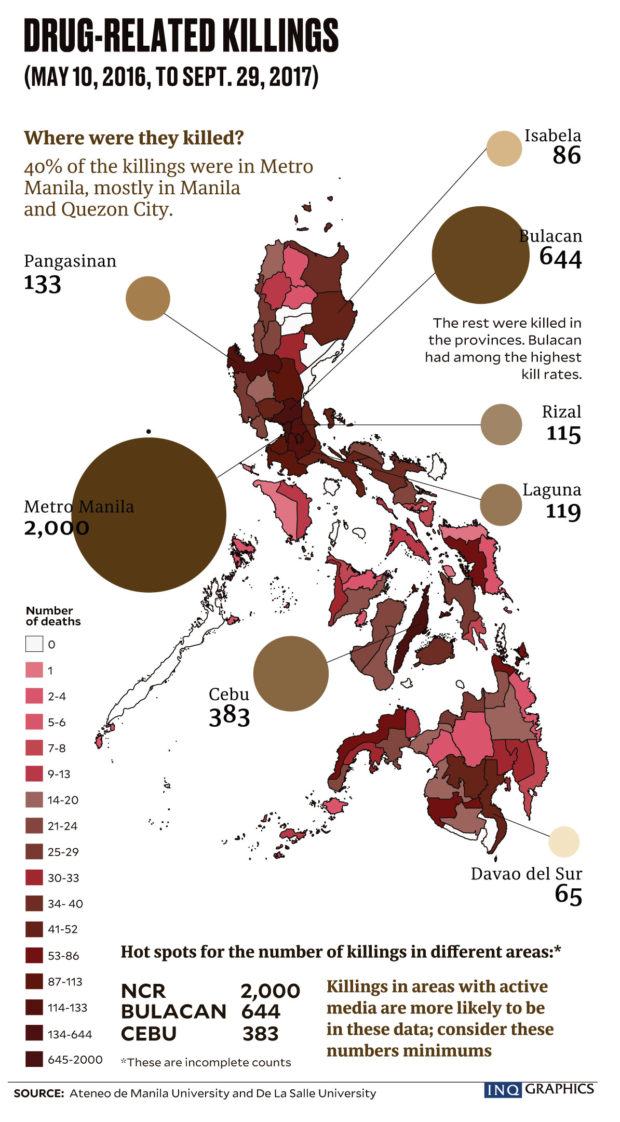

Article continues after this advertisementRonaldo Morales was among the thousands killed by police and recorded in a new study by researchers from Ateneo de Manila University and De La Salle University.

Data culled and analyzed from news reports from May 2016 to September 2017 showed that Morales fit squarely in the profile of the majority of the victims of the bloody drug war: male, poor and shot dead in an alleged exchange of fire with police during a drug bust.

The findings, which were presented to the public on Monday at Ateneo in Quezon City, were the initial results from two research projects that aimed to propose policies and solutions to the drug problem.

Clarissa David, one of the lead researchers, said the data set provided a look at only a fraction of the killings in the drug war.

But in the first 16 months since Mr. Duterte won the presidency, the research counted up to 5,021 drug-related killings, both by police officers and unknown assailants.

Manila proved to be the most bloodied in the National Capital Region, with 463 killings, followed by Quezon City and Caloocan City.

Police data

The Philippine National Police, however, had placed the total number of drug suspects killed at 3,987 from July 2016 to January 2018.

Drug-related homicide cases reached 2,235.

While the occupations of the majority of victims were not mentioned in the news reports, David said that in the reported cases, “it was clear that the victims were poor.”

The victims were tricycle drivers, construction workers, vendors and like Morales, garbage haulers.

Morales’ wife, Rowena, said her husband worked hard as a trash hauler on the Payatas dump to support their family. The long hours and grueling conditions, however, later took a toll on his health.

“In 2009, we went to Lung Center of the Philippines. He already had complications,” she said in an interview last week.

“He was later diagnosed with lung cancer. In 2016, he was given only a month to live. But on the same night, the cops killed him,” she added.

Killed by cops

Her husband became one of the 2,753 people killed by police in that period, which accounted for 55 percent of the total killings.

Of the total deaths, most were male and nearly half were alleged drug pushers, the study showed. Out of more than 2,000 alleged drug peddlers slain, 62 percent were killed in police operations.

Nearly half of all the victims allegedly had illegal drugs on them. At least 774 were found with fewer than five sachets of “shabu,” or crystal meth.

After Morales and Baldosa were killed just outside their homes, police said officers recovered three sachets of suspected shabu from them.

A fifth man, Efren Morillo, survived and later belied the police claim, providing the foundation for a writ of amparo petition that was granted by the Supreme Court.

No police operation

Like Morillo and many other victims, Rowena Morales, too, belied the police report that her husband was killed in an operation.

She said that on the night of her husband’s death, he stepped out of the house, wearing only an undershirt and briefs to relieve himself in a nearby creek.

“Right before 10 p.m., police barged into our house and aimed their firearms at us. I didn’t know what was happening outside until the police left and I looked for my husband,” Rowena said.

“We found him in the hospital morgue. He had been shot once through the mouth, with the bullet exiting through the back of his head,” she added.

ICC investigation

As the killings in the drug war continued to rise two years on, the researchers and academics expressed hope that the patterns shown in the study would be used to provide evidence-based solutions to the drug problem.

Lawyer Michael Yusingco said the study could be used as a takeoff point in the ongoing investigation of the International Criminal Court into the killings in President Duterte’s war on drugs.

“What this antidrug campaign has focused on is drug use, but it is merely a symptom,” psychologist Regina Hechanova said. “The government must be focused on the root causes and we are seeing more and more through these data that these are poverty and unemployment.”

Ronald Mendoza, dean of Ateneo School of Government, said drug smuggling and supply must also be curbed.

“Unless this is addressed, basically we are facing a never-ending stream of the challenges from moving forward,” he said, adding that if the killings continue, the Philippines “may run out of citizens one day.”

But like many of those left behind, Rowena Morales finds moving forward a challenge.

Left to raise her family on her own, she now works as a sweeper in the village, while her son, 15, has chosen to leave school to help her.

He now works as a garbage hauler—like his father.

“Justice? There is no such thing as justice or rule of law for the poor,” Rowena said. “Justice is only for those who can afford it.”