Three steps from heaven: Boracay B.C. (before ‘cesspool’)

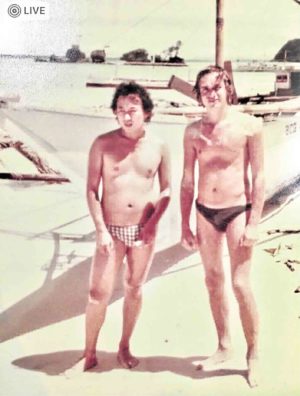

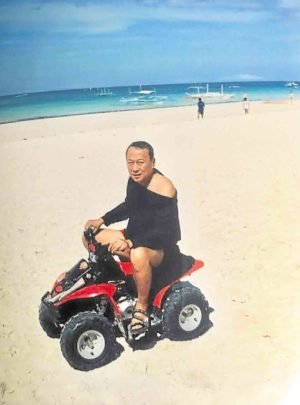

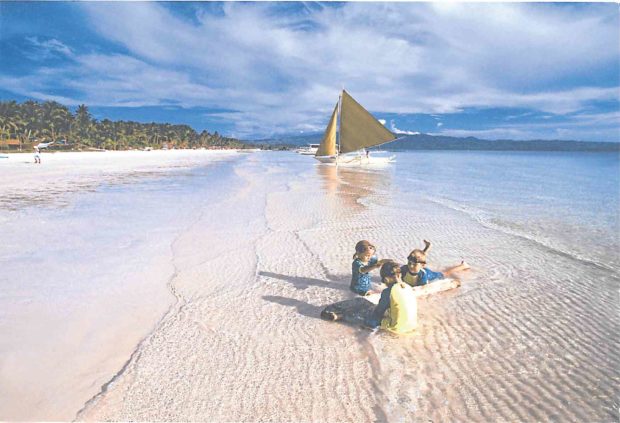

PARADISE FOUND Sand so white the sun’s rays bounce back (above); Louie Cruz with German boyfriend Robert Schmidt in 1971 (top, right); Cruz riding an all-terrain vehicle in Boracay in the 1990s, shortly before he decided to live on the island. —GEORGE TAPAN

The first time Louie Cruz set foot in Boracay, he found it so beautiful that he described the island paradise in Malay, Aklan province, as “three steps away from heaven, almost perfect.”

Wading into the water, he recalled seeing colorful tropical fish circling him, “looking very friendly and curious.”

This was the early 1970s, when Cruz — the third of seven children of the late journalist and diplomat J.V. Cruz — flew in from Germany, where the family was based, for a vacation in Manila.

Invited by the Elizaldes to a five-day stay in their Boracay property, he flew with the group in a private plane that landed on an improvised airstrip in Caticlan.

Cruz recalled: “The sand was so white that the sun’s rays bounced back and your feet didn’t feel the heat when you stroll on the beach.”

Article continues after this advertisementAt night, the skies cluttered with “millions of stars” mesmerized him. During the day, coconut trees crowded each other so tightly that some of their trunks “were bent in a certain way” as if seeking their share of the sun.

Article continues after this advertisementCruz was in his 20s when he fell in love with Boracay despite — or maybe because of — its isolation and the lack of creature comforts during the early years.

There was no electricity. For food, the household staff of the Elizalde house had to go to outlying barrios.

“I asked the caretakers, ‘Who lives on this island?’ And they told me, ‘No one.’ I walked on the beachfront from end to end, and saw no one. I didn’t even see any chicken or pigs. There was nothing.”

At the time, Cruz recounted, people went to puka shell beach in Yapak — one of three barangays that comprise Boracay — to look for shells that “Liz Taylor had made popular when she wore it.”

Still awesome

Edd Fuentes came to Boracay much later, in the ’90s, although his family hails from Kalibo, the capital of mainland Aklan.

“[The island] was no longer virgin by then, but it was still awesome,” recalled the president and CEO of public relations firm Fuentes Manila.

After buying a property in Boracay to build a vacation home, Fuentes said he saw a business opportunity and grabbed it. The property was converted into a boutique resort with 14 rooms.

“Then I was offered more properties in various parts of the island, in Stations 1 and 2,” he said, referring to the more populous southern tip of the island. “The prices at the time were too affordable to resist.”

For Cruz, settling in Boracay meant contemplating a future without his parents who died within a span of two years.

“After living in Europe for 25 years, I asked myself where I wanted to go. I was looking for a zero-stress lifestyle, where there’s no traffic—that’s Boracay. No need for a driver—that’s Boracay. No dress code—that’s Boracay,” he explained.

The island would be his home for eight years, starting in 2000—when he put up a restaurant, McSandro, in the then newly built D’Mall at Station 2.

Cruz was known in Manila’s elite circles as a bon vivant who helped shape the city’s nightlife with the haunts he ran, such as the iconic Giraffe.

He befriended owners of various resorts in Boracay, including members of the Tirol clan who owned Pearl of the Pacific. (The Tirol patriarch, Ciriaco S. Tirol, was originally one of Boracay’s titled landowners). Cruz said he convinced the resort owners to celebrate the New Year by having “a countdown from the 25th of December until the 31st.”

At the time, tourists flocked to Boracay only on the hot months of April and May. “My father used to say, ‘If the Eiffel Tower is beautiful during summer, it should be just as beautiful during winter, spring and all through the year, even if it rains.’ So I would tell the resort owners the same thing: You should package the island as a destination throughout the year. Number one, I said, Asians and Filipinos are not fond of the sun. So even if the sun is out, they don’t care. Number two, it’s near Manila.”

Red flags

But as Boracay gained fame as one of the best beaches in the world, Cruz said he saw red flags and warned his friends that “resort owners were breaking the zoning laws.”

Fuentes recounted: “When I built my beachfront resort, I was told about the 25 meters plus 5 meters [required easement] between the shore at high tide and structures on the beach when I applied for a building permit. The municipal engineer’s office measured the setback and I complied with the rule. But I saw that some of my neighbors were not compliant. That was the first time I realized that some people could get away with violations.”

Another red flag, for Cruz, was the holding of events sponsored by competing consumer brands. “A lovely, romantic island should not be a party island. Parties mean noise pollution. They should be held inland and not on the beachfront. The older generation stopped going because eventually, it was just noise and drinking … It was good for the younger crowd but the nightlife should have been segregated.”

Fuentes became a member of the Boracay Foundation, the association of resort and business owners whose main objective was protecting the island.

PUSHING THE LIMITS Boatmen prepare to meet the flood of tourists that have made—and unmade—Boracay. —LESTER LEDESMA

“Initially, I was an active member. In fact, I was part of the committee that suggested the environmental fee (P50 per tourist, now raised to P75) to solve the growing garbage problem. The municipal government had no budget!” Fuentes said.

But he soon discovered that even among the foundation’s members, not everyone was compliant with the rules meant to conserve the island’s pristine waters.

Which was why Cruz said resort owners should stop blaming only the government for Boracay’s six-month shutdown starting on April 26, “because the resort owners themselves were all the while busy making money.’’

Speaking at a business forum in February, President Rodrigo Duterte framed the problem starkly, saying Boracay had turned into a “cesspool” because of sewage from tourism establishments flowing directly into the sea. A total of 195 businesses have been found to be unconnected to the island’s sewerage system, according to the Department of Environment and Natural Resources.

Wake-up call

Cruz added: “I’m in favor of the temporary shutdown because what really happened was that resort and business owners forgot that, though they own or lease land on the island, its beachfront is for everyone. They just didn’t care about the sea and were dumping everything there.”

Fuentes said that he, too, welcomed Boracay’s rehabilitation. “It’s about time. If it has to be temporarily closed, so be it. What I cannot appreciate, though, is that, up to now, there is no clear and definite plan on how the rehabilitation would be done. It’s only now that we are getting some guidelines on a piecemeal basis. But everything is still a big ‘what happens now?’”

Closing Boracay is a wake-up call, Cruz said. “I was even telling the owners, once their resorts become popular throughout the year, the room rates should go down. They never did!”

He slammed the local government as well. Despite the taxes collected, Boracay doesn’t even have a hospital, Cruz said. “These are in your mind when you live there. I stayed there for the beautiful sunset every day. But I knew I was going to leave the island one day because I’m not from there.”

But there’s hope, he assured. “The residents have to change their attitude. It’s not only the sewage system, it’s the people’s mindset that has to change. The residents and resort owners have to change their values and learn to appreciate that the island is not a piggy bank.”

Fortunately, Cruz said, nature has a way of healing itself—but with people’s help.