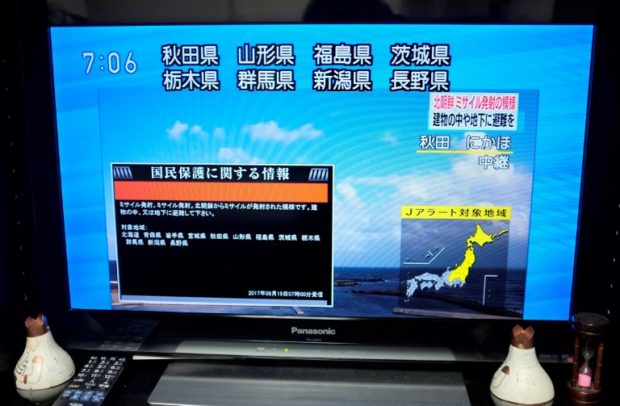

This photo illustration of a television news report in Tokyo shows a “J-alert” being issued telling the public about North Korea’s missile launch on September 15, 2017. Millions of Japanese woke up in the early hours on September 15 as North Korea blasted its second missile over the country in less than a month. AFP

TOKYO, Japan — On January 5, as Tokyo’s commuters were struggling back to work after their long New Year break, blaring sirens from every phone pierced the sleepy atmosphere: “strong” earthquake coming.

The message delivered via the country’s alert system, part of its much-hyped J-Alert mechanism, warned of a big one directly hitting the Japanese capital — potentially on the scale of the devastating 2011 earthquake that wrought massive destruction.

Millions braced for impact… but it never came.

It turned out that the system, which aims to give a precious few seconds to find shelter before a major earthquake strikes, had been tricked by an unusual seismological coincidence.

Two minor tremors struck at almost exactly the same time in separate locations, making the alert system mistakenly believe a massive jolt was on its way, the meteorological agency admitted.

Even Prime Minister Shinzo Abe was caught off-guard — with TV footage showing him checking his phone as alarms echoed in his office ahead of a cabinet meeting.

It was not the first false alarm for the system, a major component of Japan’s J-Alert launched with great fanfare in 2007 as a way to save lives in a country constantly under threat of earthquakes and — more recently — North Korean missiles.

Several countries have introduced similar early warning systems for major earthquakes, with most focused on a particular, quake-prone area.

But Japan’s system is unique in its breadth of coverage, said Issei Suganuma, a scientific officer at the meteorological agency.

“Our system covers the entire country with some 1,000 observation points across the nation,” he told AFP proudly.

‘Safety tips’

At the agency’s Tokyo headquarters, at least seven uniformed officers keep watch around the clock in the earthquake observation room.

Large screens hang on the walls showing real-time seismic waveform data.

In the case of a cataclysmic earthquake, they detect initial minor tremors through seismometers and immediately warn local governments via J-Alert seconds before the first strong jolt is felt.

The agency also directly sends SMS messages and whooping alarms to local residents’ phones.

Broadcasters receive signals to flash breaking news alerts and bullet train services are immediately suspended.

When the 9.0-magnitude earthquake hit Japan in 2011, the system successfully warned residents between six and 40 seconds before the first major jolt.

The J-Alert system also warns of missiles, particularly relevant during a rise in tensions with North Korea last year.

In the case of a missile launch, US spy satellites or Japanese Aegis ships detect the initial signals and transmit them to Japan’s defense ministry.

The ministry swiftly plots the course and speed of the missiles before the prime minister’s office triggers the system, issuing a warning between two and five minutes before they fly over the country.

With the 2020 Tokyo Olympics looming and 40 million tourists expected to visit, the government has started providing alerts in multiple languages through a “safety tips” app.

‘Not good enough’

But J-Alert has also faced criticism. In addition to technical difficulties that can result in false alarms, many feel the warnings do not come soon enough.

When North Korean missiles flew over Japan in August and September, residents complained there was no time to find shelter.

“We were told to go inside a stable building or underground, but how can we find such places in a few minutes?” said Atsuko Koide, 64, a housewife in Akita, northern Japan.

“It’s especially useless for elderly people who can’t move quickly,” Koide told AFP.

A government survey conducted last year found just five percent of respondents actually evacuated or took protective measures in response to the missile warnings.

Some respondents said they had no time or did not know where to go, while others said evacuation was pointless.

“J-Alert alone is not good enough,” said Mitsuru Fukuda, professor of risk management at Nihon University in Tokyo.

“It is clear that there is a limit to what the country and local governments can do,” Fukuda told AFP.

Fukuda urged authorities to raise people’s awareness of the measures they can take to protect themselves before government help arrives, saying: “It is individuals who decide and act after a warning.”

Following the false alarm earlier this year, the meteorological agency has introduced a new analysis tool to avoid mistaking multiple smaller quakes for a single big one.

However, agency officer Suganuma acknowledged the system’s limitations.

“Since we have to issue a warning in quite a limited time, sometimes things may not go as planned…. It’s hard to achieve 100 percent for sure,” he said. /cbb