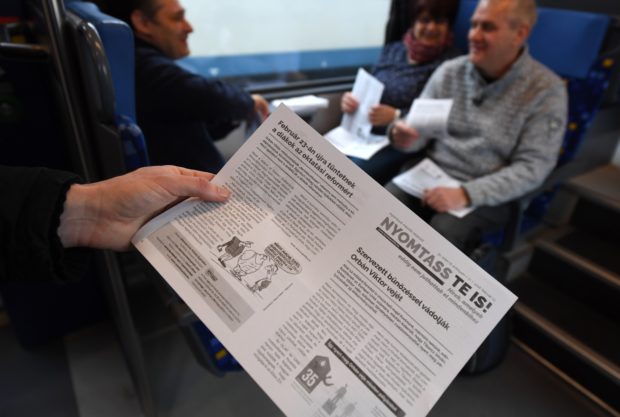

A picture taken on February 16, 2018 at the Southern railway station of Budapest shows activists of civil organization ‘Nyomtass te is!’ (Print it yourself!) preparing their own printed leaflets in a train on their way to the provincial city of Szekesfehervar. Hungarian general elections will be held on April 8, 2018. (AFP PHOTO / ATTILA KISBENEDEK)

As a student in 1980s communist Hungary, Janos Laszlo used to help out in the famous “samizdat” movement that published underground, homemade news in Soviet Bloc eastern and central Europe.

Fast-forward to 2018 under strongman Prime Minister Viktor Orban — who is running for re-election on Sunday and dominates Hungary’s media landscape — and Laszlo is back at it with his “Print it Yourself” venture.

Armed with a stack of A4-sized news pamphlets that he puts together and prints at home or at friends’ print shops, once or twice a week he sets off for the countryside to spread the word — literally.

“There aren’t many independent media outlets left in Hungary anymore,” the 60-year-old told AFP aboard a train to the provincial city of Szekesfehervar.

“So I bring their content to people outside Budapest who are particularly isolated,” he said.

According to Laszlo, a former journalist, people outside the capital, especially the elderly, get their news mainly from regional newspapers or state television and radio.

But all have been under strict central control since a radical overhaul of media under Orban, in power since 2010.

Readers of Laszlo’s weekly paper though can catch up on six or seven stories — from corruption scandals to street protests — that are reported only in independent outlets, typically Budapest-based news websites.

“We felt a moral obligation to provide a balance to the distortions elsewhere in the media,” said Emese Nagy, 48, one of five helpers on the train folding the newsletter pages in two.

“If an ordinary person sees something in a newspaper or on TV then chances are he thinks it must be true, even if it is not,” she said.

Once off the train the team hand the pamphlets to pedestrians, or leave them at busy spots like train stations or underpasses, or drop them in mailboxes along village lanes.

Takeover

Laszlo said he decided to act last August after business interests close to Orban completed the takeover of Hungary’s popular regional newspapers with circulations often exceeding those of national titles.

“That was the last straw, even though it was just the latest stage in the systematic elimination of the free press here in recent years,” he said.

Public television and radio channels were merged soon after Orban swept into power, and given the same content from the now tightly controlled state news agency.

In recent years, most commercial media critical of the government have been bought by business interests close to the ruling Fidesz party.

All 18 regional papers are owned by either Orban’s hometown mayor Lorinc Meszaros, or Hollywood film producer and casino magnate Andy Vajna, or Austrian tycoon Heinrich Pecina.

Most of the papers’ staff have left or been fired, while their political content closely follows the government’s relentless anti-immigration agenda.

“There are hardly any literate people left at the paper, there’s certainly no real news anymore,” Erno Klecska, former editor of the Fejer Megyei Hirlap, the Szekesfehervar-based county paper, told AFP.

“It’s like the powers-that-be want to close down every channel of potential criticism that exists,” he said.

Samizdat

As polling day approaches, government-friendly media have intensified warnings over Orban’s main campaign themes: immigration and interference by Brussels, and US billionaire George Soros.

Laszlo said demand for his newsletter has also been increasing.

On the “Print it Yourself” website, people can download the latest issue, print it at home, and distribute it in their own locality, or Laszlo’s team can give a helping hand with printing.

“We’ve just sent 10,000 copies down to Szeged (southern Hungary),” he told AFP.

In Szekesfehervar, a city of some 100,000, most passersby accepted a copy, although one man stopped to rip it up and hand back the pieces with a grin.

“When Fidesz supporters are confronted with scandals and strong headlines it winds them up,” Laszlo said.

Another local, Eva Tolvaj, sat on a bench folding copies and said she agreed “with every word” in this “little piece of samizdat”.

Back in the 1980s Laszlo helped to circulate periodicals and banned books printed by “samizdat” publishers.

For Roza Hodosan, who ran an underground publishing house specializing in works banned by the communist authorities, Laszlo’s initiative is “important”.

“This is something at least, but it can’t reach enough people to compensate for the overwhelming dominance of the government media,” the 63-year-old sociologist told AFP in Budapest.

“Then, we could see the end as communism got milder toward the end of the decade. But now it seems as things are getting more restrictive again, and that the world is entering dark times,” she said. /kga