Driven by a mission, he takes passengers for a ride

CEBU CITY—This Uber driver will not only drive you to your destination; he’ll also help you stay on the straight and narrow path.

When Alain Joseph Aliño, 47, talks to his passengers, he allows them to see his struggle against illegal drugs, the demon that gripped his life for 18 years.

The former addict, who is involved in rehabilitation programs in Mandaue and Cebu cities, has been giving testimonies in schools and private companies but said that being an Uber driver could help him deliver his message better.

He’d like to spare families from the pain his loved ones went through because of his addiction, said this fourth of five children born to two prominent broadcasters here.

But while his siblings excelled in school, Aliño grew up with low self-esteem. Out of curiosity, he started smoking at 13 and would steal cigarettes from his parents who were heavy smokers.

Article continues after this advertisementTo release his pent-up resentment against his parents who scolded him for his lack of ambition and pitiful grades, he turned to alcohol that his neighbors gladly offered him. Instead of sound advice, they handed him bottles of beer so he could “forget” his problems.

Article continues after this advertisementThe same neighbors introduced Aliño to marijuana. Cough syrup came next and then injectable painkillers and later, “shabu” (crystal meth).

Drug of choice

But injectable painkillers became his drug of choice because aside from the high they offer, he enjoyed the pain when the needle broke his skin.

Life had become a downward spiral by then.

After transferring to another school and shifting to a secretarial course because of failing grades, Aliño found himself using his tuition and stealing stuff to buy drugs.

His parents thought he was a kleptomaniac and sent him to a psychiatrist. But Aliño didn’t finish his sessions, managing to convince his doctor that he was OK. To prove it, he worked as a radio reporter.

When his girlfriend got pregnant, he thought this was the push he needed to turn his life around. But he was sober only for a week.

“During our wedding day, I was in Kamagayan (red light district), shooting (injectables),” Aliño said.

In fact, he added laughing, “When I looked at the wedding gifts, I thought to myself ‘so many (items) to sell (to support my habit)!’”

Two days after his wedding, he was back to drugs. His wife eventually left him, bringing with her their son.

Six rehab stints

In 1996, Aliño’s mother had him picked up by the police after he stole the microphone and cassette of the radio station where she worked.

Threatened with jail time, he agreed to go into rehab. But his six-month stint in the government-run Drug Rehabilitation and After Care Center (DRACC) only led him to where he could get drugs cheaper.

It was also the start of his six trips to rehab centers—thrice at DRACC and thrice in private facilities.

“At the rehab center, my mind and body would switch to rehab mode and I would memorize all the programs and activities in the place. Outside, however, I would switch to addict mode,” Aliño said.

Even his father’s death, for which he felt partly responsible, did nothing to convince him to change.

His father had confronted him about the money that Aliño took from a friend. He denied taking the money although in truth, he used it to buy drugs.

A week later, his father succumbed to a heart attack.

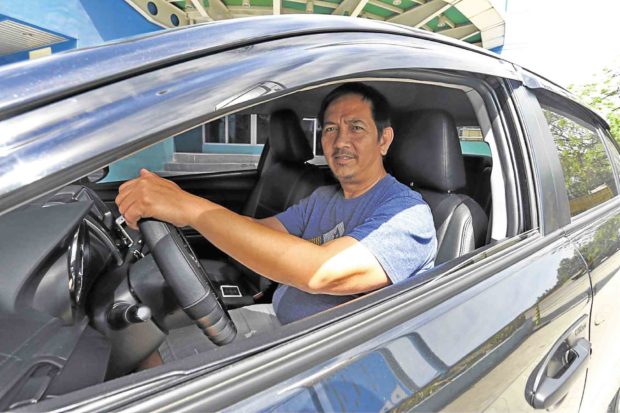

DRIVEN Uber driver Alain Joseph Aliño shares his life story with passengers. —PHOTOS BY JUNJIE MENDOZA

Deported

To keep him away from friends who were drug users like him, Aliño’s family sent him to the United States where he ended up hanging out with Mexicans involved in meths. He was later deported after being caught with a small amount of meth.

Thinking that he was already a hopeless case, his family finally gave up on him.

By this time, Aliño was on his sixth rehab admission. But he was abruptly released from the facility when his family stopped paying the center. They also refused to take him back.

“I realized I had nowhere else to go,” he recalled.

A laundry woman at the rehab center allowed Aliño to stay in her shanty in Consolacion town, northern Cebu, on one condition: he should stop using drugs.

He agreed.

For the first time, Aliño experienced how it was to have nothing: no money, no resources, no parents. Before they could eat, he had to gather firewood. His room was a shack outside the laundry woman’s shanty.

Embarrassed by the old woman’s generosity, Aliño worked as janitor/messenger at a church-ran foundation for P1,500 a month.

When he learned how to use the computer, he was promoted to researcher. This time, he left the woman’s shanty and rented a windowless room for P500 a month.

“For the first time, I was on my own. I had no one to talk to. I wanted to go home but I was scared that (my family) would never forgive me,” he said.

Narcotics Anonymous

To ensure his road to recovery, Aliño joined Narcotics Anonymous and had a mentor, also a former addict, whom he would call whenever he craved drugs.

He joined the group’s 90 meetings in 90 days which helped him acknowledge that he had a problem and had no one to blame but himself.

Slowly, friends started to reconnect with him, including a female classmate whom he avoided after he stole a bicycle from her house. This classmate also helped him get in touch with his mother whom he had not seen for two years.

“My sponsor told me that (meeting my mother) was part of the program—to make amends with the people I hurt,” Aliño said.

He called his mother at the radio station but only her secretary received his first three calls. He wanted to give up but his friend egged him on. On the fourth call, his mother picked up.

His throat dried up. After a brief silence, he managed to say “Hi, Ma. Can I invite you to dinner?”

To his relief, she agreed.

Three red roses

As advised by his mentor, Aliño arrived early, bringing three red roses bought at P5 each, and a card where he poured everything he wanted to say to his mother. He was 42 at that time—the first time he had ever brought flowers for someone.

“When my mother arrived, I gave her the card and roses. My first words were ‘Sorry, Ma.’ And her reply was ‘What kind of a drama is this?’”

That broke the ice and they started talking. But Aliño didn’t want to go home yet and his mother did not insist.

Not hopeless cases

When he later told her that he planned to resign from the foundation, his mother offered him a job as her driver. He finally went home, but decided to sleep in the living room out of fear that he might be blamed should something go missing.

He also reached out to his ex-wife and son to seek their forgiveness.

Five years later, Aliño has his own business and has hired a driver for his mother. He is now a rehab practitioner duly accredited by the Department of Health and is involved in various rehabilitation programs in Cebu and Mandaue cities.

He even plans to put up his own rehab clinic.

His experience, said Aliño, is living proof that addicts are not hopeless cases.

“There is hope for each one of us,” Aliño said. “Killing (addicts) is not the right thing to do. We are sick, we need help.”