On Feb. 1, Rustie Otico told some friends in a text message sent through his sister Edith: “I’m here lying in my hospital bed. Hopefully I’ll be released in a few days. Keep going, you guys.”

The message heartened me, I told the writer Elizabeth Lolarga, who had relayed it. He sounded good, I told myself, sounded restless and chafing at the bit, aching to get the heck out of there and back to what he had called home for the past two and a half years: his sister’s hilltop house in Barangay Mojon in Belison, Antique.

In the end he did manage it. On Feb. 3, he was released from Antique Medical Center and taken home, where he expired at 2:30 p.m. on Feb. 7, eight months shy of 80.

Thus did a stalwart of Philippine journalism sign off, as lightly as a falling leaf, as reticently as he had lived. Yet if there’s one thing today’s reporters are missing out on, it’s the ministering hand of Rustie Otico, the desk editor’s editor, a legend in the many newsrooms that benefited from his work.

Among those newsrooms was that of the Inquirer, where he was a member of the News Desk from March 1992 to March 1999. Slight and mild-mannered, he was forceful in straightening out a reporter’s copy — quick to spot in the welter of words not only high and low crimes in grammar but also lapses in logic and inaccuracies of fact. In fact, he shaped many of today’s journalists in the way of clear and truthful reportage, with correct attribution and verified sources.

It helped, of course, that the ex-future aeronautics engineer had perspective. He knew the nuts and bolts of his profession, having started out as one of the founders of the regional paper The Trail. From there he worked at the Manila Chronicle until the darkness of the Marcos dictatorship descended and, along with many others, he was forcibly enlisted in the army of the unemployed. He survived martial law but, like many others, it was not a mere “thingy” to him. He went on to work in the newsrooms of the major dailies and continued serving as desk editor or consultant in newspapers and magazines after his retirement from the Inquirer in 1999.

Meticulous and ruthless

“Rustie was a meticulous editor, well-respected by both reporters, whose copy he painstakingly hammered to perfection, and his fellow editors, for whom he set a lofty standard for editorial craftmanship and integrity in the profession,” said Jun Engracia, former news editor of the Inquirer.

He was, recalled a colleague of his who asked not to be named, “ruthless with the copy of young writers but kind and patient in showing the way to good writing.”

The recollection of him in that aspect is near-universal: excellence in his field.

In 1998, by some miracle, members of the print media bestirred themselves and recognized the efforts of Rustico Estañol Otico, senior desk editor of the Inquirer. He was one of two recipients (the other was Pocholo Romualdez, executive editor of Ang Pahayagang Malaya) of the Editors’ Choice Award given by the Philippine Press Institute and Philippine Press Council. They were, as then Inquirer reporter and now Metro editor Volt Contreras wrote, “the craftsmen silently chipping away at flawed syntax and grammar to produce keen and engaging newspaper articles, bringing out quality that makes reporters win awards.” It’s uncertain if anyone else has similarly been awarded since.

But editing copy was not the only way with which Rustie romanced the written word. According to his sister Victoria, “his most treasured journalistic accomplishment is a short story, ‘The Long Journey Home,’ published by the Philippines Free Press in the 1960s.”

I remember that he once wrote an article for Celebrity magazine on the Olympian Lydia de Vega, wrote it like the craftsman that he was, careful to describe her passage, gazelle-like, on the track; thorough in names, places, and dates, and ultimately worrying whether a certain comma was misplaced and should be forthwith deleted.

“Few people,” said Engracia, “knew his passion for sports, particularly track and field, both as a fan and as a professional. He followed the career of Asian track queen Lydia de Vega in the 1980s, and his encyclopedic knowledge of the sport would put any sports writer to shame.”

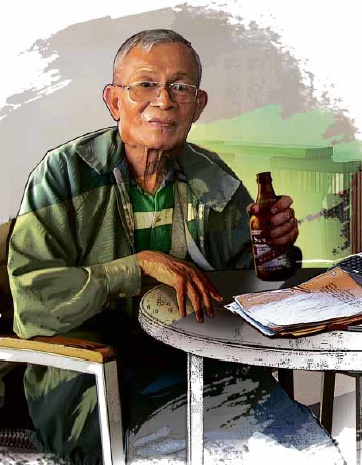

Man with a bottle

Yet that’s hardly all there was to Rustie Otico, who loved the arts, and who was once observed wiping his eyes after listening to Cecile Licad play Liszt’s “Dante” Sonata.

And who, at the end of the night’s work, took to drink like the proverbial duck to water. Like Dylan Thomas, he “liked the taste of beer, its live, white lather, its bright-brass depths,” and those who knew him well, and drank with him as well, remember those long nights of inebriation when words flowed fast and beer (or gin) flowed faster — everyone brash and young (though aging) then, recklessly flinging themselves on the rock of night.

In the fog Rustie sat: man with a bottle, attentively listening to the conversation or just sitting quietly, musing on his cigarette (which he consumed by the carton).

Close to morning, recalled his anonymous colleague, Rustie would “hobble to a waiting taxi, the stupor easing the burden of the day, [creating] a lull before the next. Goodbye, friend.”

For all that, Rustie was the “best brother and best uncle one could ever ask for,” said his sister Victoria. “All his nephews and nieces called him ‘Tatay,’ being a father figure to all of them. My parents couldn’t be more proud of him as a son, being the smartest in the family, and who sacrificed the most in helping his younger siblings through college. As a brother, he was very loving and thoughtful, always saving something for the older ones in case they come home.”

Said Engracia: “To friends and colleagues, Rustie was simply a great person.”

Yes, and like most of us, he literally won some and lost some. Betting on the horses, he put a bonus on friends’ tables with a flourish whenever he got lucky.

And like most of us, his dream was to win big. He once described to me the scene in his mind’s eye: He throws down the highest hand after a troubled night of playing. He gets up from the table, collects his winnings, and drawls, “Gentlemen, this is my last game.”

And then he saunters smiling into the night.