Iloilo stages grandest Dinagyang Festival

RAYMOND JAVIER / PHOTOGRAPHIC SOCIETY OF ILOILO

ILOILO CITY—As the city’s Dinagyang Festival turns 50 this year, the drumbeats are louder; the festivities, livelier; and the colors, brighter.

Organizers describe this year’s celebration as the biggest and grandest in its history.

Among the highlights of the festival, the Kasadyahan regional cultural contest was held on Saturday and the Ati tribe competition today. New events and activities have also been lined up for the festivities.

The city government has allotted P18 million for the event, while the Iloilo Dinagyang Foundation Inc. (Idfi), which managed the festival, raised at least the same amount.

From the city funds, P15 million was given as subsidy to competing tribes, according to Ramon Cua-Locsin, Idfi president. This included P1 million each for the tribes in the Ati tribe competition and P500,000 to each of the 10 groups taking part in the Kasadyahan regional cultural contest.

The subsidy has been the biggest allotted to the competing groups, which have been sponsored by private companies and organizations.

Events have also been expanded to areas outside the city’s central business district, where the contests and street dancing are concentrated.

Float parade

The first Dinagyang Float and Lights Parade was held on Jan. 27, from Infante Avenue to Iloilo Business Park, the 72-hectare mixed-use complex of Megaworld Corp. in Mandurriao District.

About 50 floats joined the parade, which traversed Sen. Benigno Aquino Jr. Avenue, the center of investments and of the city’s economic boom in recent years.

Cultural performances from New Zealand, South Korea and Hawaii were also featured in another new event, the International Cultural Night, held on Jan. 26.

Mayor Jose Espinosa III said that even with the grand celebration, the significance of the festival was its religious core and the 50 years of cooperation among government officials, church leaders and the community people.

He said this made Dinagyang one of the most popular and anticipated festivals in the country.

Retired Western Visayas tourism officer Edwin Trompeta said the festival had not only grown but had also evolved from what it was five decades ago when it first struggled to establish its own identity.

Unlike other festivals held in honor of Señor Sto. Niño every third Sunday of January, Iloilo’s Dinagyang festival is held a week later. Organizers in the 1970s decided to move it a week after the Kalibo Ati-Atihan in neighboring Aklan province.

“The Ati-Atihan was more popular then and devotees and revelers can only attend one of the festivals,” Trompeta said.

Sto. Niño replica

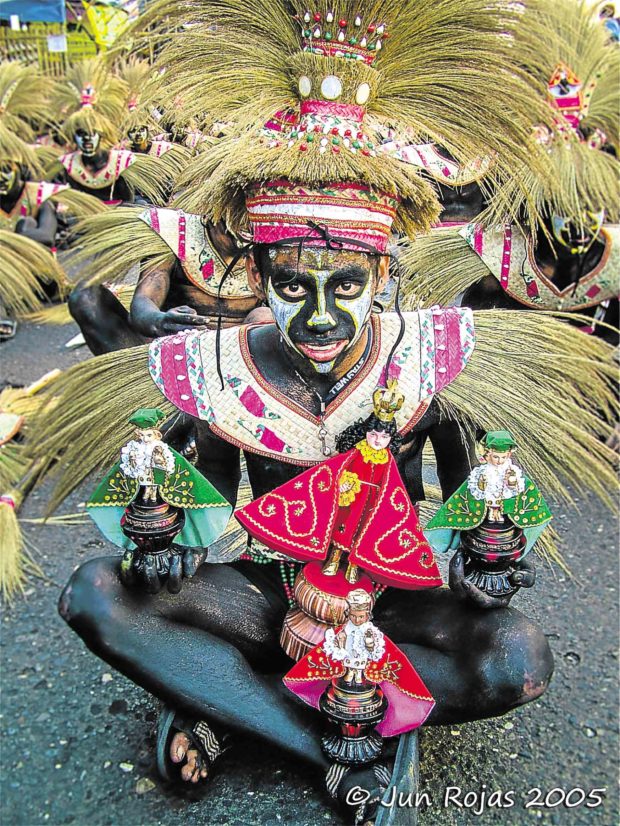

At the core of Dinagyang is veneration for Señor Sto. Niño. —JUN ROJAS / PHOTOGRAPHIC SOCIETY OF ILOILO

Iloilo’s Dinagyang originated in 1968 when Fr. Sulpicio Enderes, OSA, with a delegation of the Cofradia de Cebu, brought a replica of the image of Señor Sto. Niño de Cebu to Iloilo City. The image was brought to San Jose Parish Church where it is enshrined until now.

The first parish feast of Señor Sto. Niño was celebrated in 1969 to commemorate the event. The champion and runner-up in the Kalibo Ati-Atihan contest performed in what is considered the first Ati-Ati festival in Iloilo City.

The next year, the first Ati-Ati contest was held at Freedom Grandstand. The Majapahit Tribe of Compania Maritima won the contest.

In 1977, in order not to duplicate Kalibo’s Ati-Atihan, organizers changed “Ati-Atihan” to “Dinagyang” from the Hiligaynon word “dagyang,” or merrymaking.

Trompeta said the street dancing and Ati tribe contest was limited at Plaza Libertad unlike today when tribes perform in five judging areas in a carousel format along a 2.5-kilometer route in the city’s central business district.

He recalled that the costumes up to the 1980s were predominantly in black and brown and made of indigenous materials.

Groups that competed in the Ati tribe contests were mainly community-based, composed of people coming from the villages in the city.

Radical transformation

In the 1980s, groups based in schools started joining the contest, which Trompeta said, radically transformed the festival and the competition.

With trained choreographers and students as performers, the school-based tribes became the dominant groups in the contest.

The brisk movements, repeated change of costumes in striking colors and mobile platforms that have become the trademark of Dinagyang were introduced by school-based groups.

Locsin said the significant growth in the festival occurred in the last decade as the private sector increased its support.

But like other religious festivals, organizers have been struggling to keep a balance between its religious foundation and its increasing role as a tourist attraction.

Despite the challenges, Trompeta said, the Dinagyang would always be a source of pride for Ilonggos.

“It fosters unity among Ilonggos regardless of political and other differences,” he said.