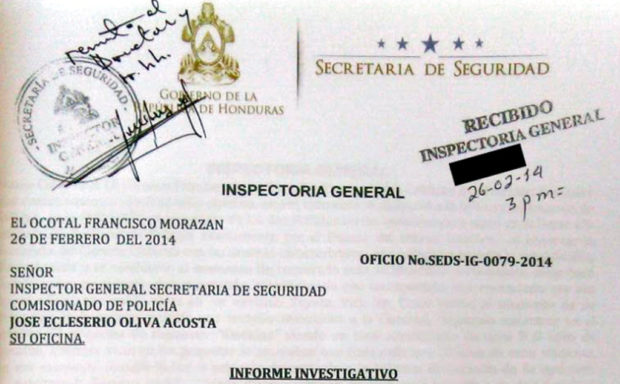

A copy of a document photographed in Mexico City, Friday, Jan. 26, 2018, shows the official header from a confidential Honduran government report that alleges the country’s new national police chief helped secure the delivery of a tanker truck packed with nearly a ton of cocaine. Honduran authorities have claimed that the document is a fake, but four current or former government officials confirmed elements of the report in interviews with The Associated Press. A handwritten notation on the header has been redacted to protect any office workers who may have handled or logged the document. (AP Photo)

MEXICO CITY — When Jose David Aguilar Moran took over as Honduras’ new national police chief last week, he promised to continue reforming a law enforcement agency stained by corruption and complicity with drug cartels.

But a confidential Honduran government security report obtained by the Associated Press says Aguilar himself helped a cartel leader pull off the delivery of nearly a ton of cocaine in 2013.

The clandestine haul of more than 1,700 pounds of cocaine was packed inside a tanker truck that, the report says, was being escorted by corrupt police officers to the home of Wilter Blanco, a drug trafficker recently convicted in Florida and now serving a 20-year sentence.

Aguilar, who at the time was serving as chief of intelligence for Honduras’ National Police, intervened after a police official safeguarding the drugs was busted by a lower-ranked officer who had seized the tanker, the report says. The handcuffed officer called Aguilar, who ordered that the officer and the tanker be set free, says the report which was prepared by the Honduran Security Ministry’s Inspector General.

The U.S. street value of the cocaine involved could have topped $20 million.

The incident raises questions about Honduras’ much-touted purge of corrupt police and the reliability of the administration of President Juan Orlando Hernandez, a key U.S. ally in the war on drugs.

On Friday, Omar Rivera, a member of the special commission that says it has purged more than 4,000 members of the National Police for reasons ranging from corruption to restructuring and voluntary retirement, held a press conference alongside a spokesman for the National Police.

They said the National Police did not have a document that corresponded to the number on the AP’s report, something police spokesman Jair Meza had told the AP on Jan. 15.

Government authorities have often had difficulties in recent years locating information in police archives. Members of the government commission, including Rivera, have said publicly since it started its work in 2016 that the Security Ministry archives were in disarray and that some police officers assigned to the archives have worked to disappear files or wipe them clean of incriminating details.

Rivera said the commission would again look at Aguilar, his deputy and the new police inspector general. “Starting today they will be subjected to a rigorous re-evaluation process to show their suitability for the positions they hold,” he said.

As Hernandez swore in his new police chief, local media reported that he said Aguilar was chosen “with the utmost confidence” and would lead “a National Police that becomes a role model for the region.”

“We are in a process of transforming the National Police, with a huge investment of financial resources,” the president said.

Aguilar, 54, vowed to instruct his officers “to follow the law and make sure the law is followed,” said local reports.

Asked about the incident, the Honduran government issued a lengthy statement saying that the investigative report is fake and doesn’t correspond to any “official communication from the Honduras Police.” The AP has not shared the document with the government due to security concerns but described its contents.

The statement also said the allegations against the police high command “lack veracity” and demanded that the news media verify information before creating “false scoops” that damage the institution and its employees.

But an ex-member of the National Police with knowledge of the investigation confirmed officials found that top officers conspired to cover up the incident, and that the handcuffed officer was later put on leave. Three other current and former high-ranking Honduran police officials confirmed elements of the report. All four spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of violent reprisals.

In addition to the report, the AP confirmed the story using other internal memos and a page from Aguilar’s personnel file summarizing his alleged participation.

A copy of a document photographed in Mexico City, Friday, Jan. 26, 2018, shows an excerpt from a confidential Honduran government report that alleges Jose David Aguilar Moran, the country’s new national police chief, helped secure the delivery of a tanker truck packed with nearly a ton of cocaine. Honduran authorities have claimed that the document is a fake, but four current or former government officials confirmed elements of the report in interviews with the AP. Here is an English translation of the excerpt: “…once he was detained, he addressed himself to us with threatening words, telling people (I am going to fire all of you shits), given the constant threats made by the Sub Commissioner Paz Murillo and due to the order and threats he received by telephone from higher-ranking officials, which he prefers to refer to or denounce before federal prosecutors or legal authorities and not in this report, Inspector Giron Miranda declares that once Sub Commissioner Paz Murillo was detained, he called Sub Commissioner Jose David Aguilar Moran, chief of intelligence for Honduras’ National Police, on his cell phone and passed the phone to him, who ordered him and threatened him to free Paz Murillo and hand over the tanker truck that was transporting the drugs, that it was an order from higher up, and to write it down as a note in the notebook at the Ceiba police station #1 and at the chief’s office at the Satuye police station, at that time, to avoid having problems with his supervisors he decided to free Paz Murillo and at the same time he handed over the tanker with the drugs that it was carrying and the truck continued on the route it had been traveling with the individuals who had been accompanying it in their vehicle who were engaged in drug trafficking for the individual Wilter Neptaly Blanco Ruiz, taking the tanker toward the home of Wilter Blanco Ruiz in the village of Planes.” (AP Photo)

Aguilar did not respond to requests from AP for comment. In public remarks Jan. 15, he said he would work to strengthen cooperation among his nation’s police and judicial agencies and make sure that officers serving under him would act with “respect for human rights.”

The inspector general’s office began its inquiry in early 2014, just as the United States was ramping up funding for collaborative anti-drug trafficking efforts in the region. The inspector general’s report blames Aguilar and other commanders for failing to discipline the officers involved and for failing to turn over the investigation to prosecutors and U.S. authorities.

The report alleges that Aguilar and other police officials sat on the case at Blanco’s request and never sent it to prosecutors or the American Embassy, “with the end goal of letting the case expire.”

Former and current U.S. law enforcement officers and a U.S. prosecutor reviewed the document for AP and said it appeared genuine.

Honduras has been an ally of the United States for decades. The strategically positioned Soto Cano Air Base near Honduras’ capital, Tegucigalpa, served as a center for U.S. efforts to beat back pro-communist movements in Central America in the 1980s, and continues to support regional anti-drug efforts and host a U.S. military presence of about 600 troops.

U.S. aid to Honduras has grown since 2014, when the Obama administration determined that it was in U.S. interests to improve security and strengthen governance in Central America. Since then, Congress has appropriated more than $300 million for Honduras, according to a recent report by the Congressional Research Service.

Honduras, with a population of more than 9 million, is one of the poorest and most violent countries in Latin America. Much of the country is controlled by criminal gangs. It has endured widespread human rights abuses and impunity at the hands of the police and military for more than a decade. Critics argue that reform efforts backed by the U.S. and the Organization of American States have been ineffective. And in recent weeks, security forces have shot and killed demonstrators protesting a disputed presidential election that handed Hernandez a second term.

U.S. President Donald Trump recognized Hernandez’s re-election last month, and certified the country’s progress in protecting human rights and attacking corruption, clearing the way for Honduras to receive millions of dollars in U.S. funds. The U.S. Senate appropriations committee, however, has put a hold on some of that money.

“There is so much illegal drug money to be made and it is so easy to get away with it, especially if you are in the police force,” U.S. Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-VT) said earlier this month in reaction to Aguilar’s appointment. “Much more needs to be known about him given the history of the Honduran police and its connections to organized crime, before there can be confidence that he has the integrity to lead that institution.”

Aguilar, a 29-year police veteran, worked his way up, serving as a regional chief along the Caribbean coast and other regions and heading up a national inter-agency security force. At one point he led a police directorate overseeing planning and “continuous improvement.” Earlier this month, Omar Rivera, a member of the government commission responsible for purging corrupt cops, told La Prensa newspaper that Aguilar was a strong candidate because of his “merits and good performance.” But a page of Aguilar’s personnel file, obtained by the AP, includes a disciplinary record summarizing his participation in the 2013 incident, alleging complicity with organized crime and drug traffickers. There’s no indication any action was taken regarding the allegations against him.

The other key player in the inspector general’s report, Blanco, got into drug running as a fisherman, smuggling boat loads of cocaine from one coastal community to another, according to records in the U.S. criminal case against him.

The trafficking grew as Blanco and his armed guards collected shipments of Colombian cocaine on the Honduran shore and took it to his property before it was moved north through Guatemala and Mexico into the U.S., according to a U.S. criminal complaint. When Blanco knew the DEA was onto him, the complaint said, he tried to negotiate a surrender, communicating on text messages that included, as his profile picture on his BlackBerry, a small plane with kilos of cocaine stacked next to it.

Blanco was arrested in 2016 in Costa Rica and extradited to the U.S. He pleaded guilty to conspiring to move 4,000 pounds of cocaine from Colombia to Honduras during a two-month period. It was widely reported in Honduras that Blanco’s arrest had sparked investigations of dozens of police and other political and criminal justice officials, but nothing about any corruption probes relating to Blanco has been publicly revealed. His attorney Victor Rocha told AP that in repeated discussions his client never mentioned police collaborating with his drug smuggling operations.

“If Mr. Blanco-Ruiz is deported to his home nation, he may well be murdered shortly thereafter in retaliation for what the Honduran press has erroneously and recklessly alleged as his cooperation,” Rocha said in court documents, using his client’s formal last name.

Drug trafficking ties within Honduras’ law-enforcement and political circles are well documented.

The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration announced last week that Honduran lawmaker Fredy Renan Najera Montoya faces drug trafficking charges in a New York federal court and the U.S. would seek his extradition. American authorities claim Najera used his influence to secure safe passage for loads of cocaine flown from Colombia to Honduras and then on to the U.S.

High-ranking Honduran police officials have been accused of ordering assassinations, trafficking cocaine and leading criminal gangs. At least six former National Police officers now face U.S. criminal charges in a federal court in New York and the DEA says their investigations into Honduras police corruption are still active. The U.S. Embassy in Honduras declined to comment.

The inspector general’s report detailing the investigation into the tanker full of cocaine explains how Blanco held sway over police.

Sources in the La Ceiba police headquarters said that before and after the tanker incident, the regional police chief Jose Rolando Paz Murillo met with Blanco in Paz’s office along with other police officials. At the meetings Blanco handed out thousands of dollars in bribes to make sure police allowed airplanes stuffed with cocaine to land and then the drugs to be transported without interference, according to the investigative report.

Among those who attended such meetings, the report asserts, were Aguilar, as well as the new National Police inspector general, Orlin Javier Cerrato Cruz, and Orbin Alexis Galo Maldonado, the man recently named as Aguilar’s top deputy. In a brief phone conversation Galo denied any knowledge. Cerrato could not be reached for comment.

It was the local head of the tourism police, Grebil Cecilio Giron Miranda, who intercepted the drug-laden truck flanked by 11 police officers in four vehicles, according to the report. He was on patrol with two other officers when an informant in a rival cartel called to tell him about the tanker full of cocaine, investigators said.

The report says Giron and his patrol took the tanker back to the police station and that, soon after, Paz, the regional police chief, arrived and began threatening Giron and the other arresting officers, telling them he would make sure they lost their jobs. Giron pointed his gun at Paz, forced him to the ground and handcuffed him, according to the report. As the higher-ranking cop’s threats escalated, the report says, the officers allowed Paz to make a phone call. Paz called Aguilar and then passed the phone to Giron. According to the officers’ statements, Aguilar told them to immediately release Paz and the tanker full of drugs.

They obeyed and the load of drugs continued on its way to Blanco’s home, the report says.

The head of the National Police at the time ordered an investigation, according to the document, but it was scuttled until a new inspector general took over in early 2014. By the time the report was submitted in late February 2014, the four-month window for police leadership to take action against those involved had passed.

All the police officers named in the report and reached by the AP said they knew nothing about the allegations. The National Police did not make any of its officers available for comment.

According to the report, Paz told the arresting officer that then police director Juan Carlos Bonilla Valladares and another top police official, Hector Ivan Mejia Velasquez, were aware of what was happening with the drugs and that they ordered his release. Bonilla told AP the documents were fake and Mejia said he didn’t know anything about the case.

Paz resigned from the police after his suspension and another assignment, a former National Police official said, and currently serves as a judge in Roatan. Paz did not return messages left at the court.

Former DEA agent Gary Hale reviewed a copy of the document and said it appears genuine.

“On the face of it, it looks authentic,” said Hale, now a drug policy and Mexico studies scholar at Rice University.

Opposition party politician Maria Luisa Borjas, who ran the National Police’s internal affairs division during her long career on the force, said she had seen the inspector general’s report and could confirm its authenticity.

“The work that the police purging commission did was of completely no use, a failure,” she said. “It was more of a source of official protection for people who have been tied to drug trafficking.”