A journalist, a priest, a diplomat and four activists who took up arms against the Marcos dictatorship are among the 11 new heroes and martyrs whose names will be added to those etched on the black granite Wall of Remembrance of Bantayog ng mga Bayani (Monument for Heroes) in Quezon City.

The other honorees come from indigenous communities, the labor and youth sectors, public service and the academe.

The annual honoring of martyrs and heroes will be held on Thursday, the 31st anniversary of the Bantayog ng mga Bayani Foundation founded in 1986 shortly after the Edsa People Power Revolution that toppled the Marcos dictatorship.

298 heroes to date

A total of 298 names are already engraved on The Wall, which stands close to the 13.6-meter (45-foot) bronze monument created by renowned sculptor Eduardo Castrillo. The monument depicts a defiant mother holding a fallen son.

The monument, the commemorative wall and other structures at Bantayog Memorial Center are dedicated to the nation’s modern-day martyrs and heroes who fought against all odds during the dark days of martial rule (1972-1986) to restore freedom, justice and democracy in the country.

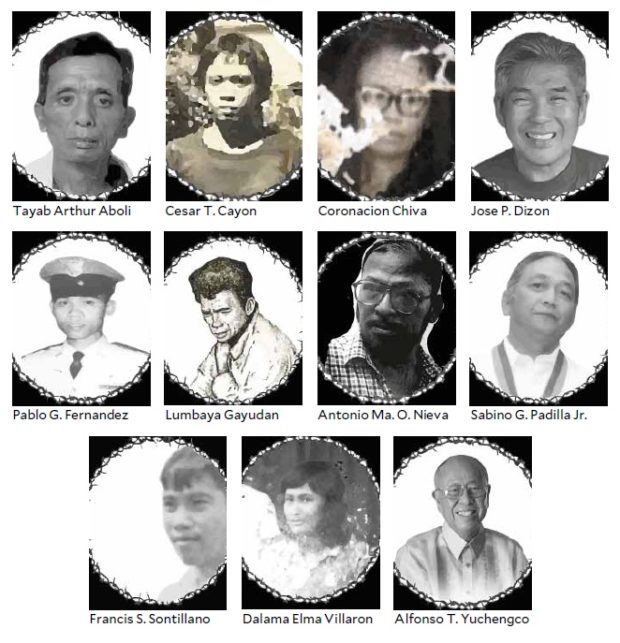

The 11 new heroes are Tayab Arthur Aboli (1942-2007), Cesar T. Cayon (1956-1983), Coronacion Chiva (1926-1977), Jose P. Dizon (1948-2013), Pablo G. Fernandez (1948-1973), Lumbaya Gayudan (1935-1984), Antonio Ma. O. Nieva (1944-1997), Sabino G. Padilla Jr. (1954-2013), Francis S. Sontillano (1955-1970), Dalama Elma Villaron (1955-1987) and Alfonso T. Yuchengco (1923-2017).

Jailed journalist

As a journalist before, during and after the martial law years, Nieva supported the causes of the working class, particularly those in media. In 1981, he organized the Brotherhood of Unions in Media of the Philippines and was among those who led “Save the Press” marches in Manila.

He was union president for two terms at Bulletin Today (now Manila Bulletin) and pushed for the establishment of unions of journalists and trade guilds across the media industry. As National Press Club president from 1984 to 1986, he turned the club premises into a refuge and haven for harassed journalists who needed protection from the dictatorship.

Nieva’s opposition to dictatorial rule and his union work made him a vulnerable target of the military. In 1983, his house was raided. He was arrested and detained briefly.

Even after Ferdinand Marcos had fled, Nieva continued with his organizing work in media. He was founding chair of the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines and he helped establish the Kapisanan ng mga Manggagawa sa Media ng Pilipinas.

He was a columnist for the Bulletin Today, where he was also a desk editor, and later for the Inquirer. He died of natural causes in 1997 while serving as the first Filipino and Asian secretary general of the Prague-based International Organization of Journalists.

Aboli and Gayudan both belonged to Kalinga indigenous communities. Aboli took up arms while Gayudan, familiarly known as Lumbaya, led his people to oppose the construction of the Chico River dam after their leader, Macli-ing Dulag, was murdered.

Villaron, the daughter of a Tumandok tribal leader in Panay, also took up arms.

‘Kumander Waling-waling’

Two other Bantayog honorees, Cayon from the youth sector, and Chiva (known as Kumander Waling-waling of Iloilo) also joined the armed struggle. Chiva was some kind of legend in the areas where she worked. Her life story is stuff for the movies.

Chiva had been a member of Hukbalahap (Hukbo ng Bayan laban sa Hapon) that fought the Japanese in World War II but that was later outlawed because of its communist ideology. Her first husband had died in the war.

Like her second husband, she spent years in prison but was released after she gave birth to a son. In the 1960s, she continued her advocacy for labor groups.

When martial law was declared in 1972, Chiva, along with student activists and professionals, was arrested and detained in Iloilo. She was rearrested for the third time and briefly detained.

The life of “Kumander Waling-waling” came to an end in a hail of bullets in 1977. She was 51.

Priest in worker’s clothing

Dizon, the only one from the Church sector in this year’s batch, lent his voice to the resistance to martial rule. He devoted many years of his life to the causes of oppressed workers. He died of natural causes in 2013.

Like Dizon, Padilla had a heart for workers. An anthropologist and professor, Padilla’s world was the university, but he went beyond the confines of the academe and stood with the “batilyos” (fish port workers) of Navotas and, later, the farmers of Isabela under threat from a land-grabbing Marcos crony.

He was detained in 1973 and in 1982 while working as research chief for a church-based social action center in Ilagan, Isabela, and helping the farmers in their struggle to keep their land. After his release, he taught at St. Scholastica’s College and the University of the Philippines Manila.

Padilla died of natural causes in 2013.

Fernandez was a public servant, elected municipal councilor of Nueva Valencia in Guimaras in 1971. But before that he was already a political activist clamoring for social change and protesting against the impending declaration of martial law.

When martial law was declared in 1972, this reserve Army 2nd lieutenant refused deployment to Mindanao to fight the Moro people. He avoided court-martial by heading for the hills and joined fellow activists there. Fernandez was wounded in an encounter with soldiers in Iloilo and later died of his wounds.

Dying young

Cayon and Sontillano were both from the youth sector. Cayon, who worked among the Higaonon tribe in Mindanao, was beheaded by his military captors. He was 29.

Sontillano died at the age of 15. A scholar at Philippine Science High School, he was an activist and a member of Malayang Kilusan ng mga Kabataan. At a protest rally in 1970, a pillbox bomb thrown by a security guard blew up his head.

Yuchengco, an industrialist who died at the age of 94, is the oldest of this year’s batch. Born to a wealthy Chinese-Filipino family, Yuchengco was highly educated. He may not have been a street activist but he gave quiet support for the antidictatorship movement, particularly the Light a Fire Movement.

After the fall of the dictatorship Yuchengco served as the country’s ambassador to China, Japan and the United Nations. He was a trustee of Bantayog and later, chair and chair emeritus until his death in 2017. Bantayog’s auditorium is named after him.

Never Again, Never Forget

Through its Never Again Never Forget Project, Bantayog addresses “attempts by certain groups to rewrite Philippine history and confuse the young generation about the truths of the Marcos dictatorship, erase its horrors, abuses and deceptions and have it remembered as a ‘golden era’ in the Philippines.”

Bantayog’s activities include publishing biographies, holding forums, disseminating information, film showings, roving exhibits and museum tours.

The Bantayog complex now includes a building which houses a small auditorium, library, archives and a museum. Its 1.5-hectare property was donated by the administration of President Corazon Aquino through Land Bank of the Philippines in 1986.

The Bantayog foundation is chaired by former Sen. Wigberto Tañada. Former Senate President Jovito R. Salonga served as chair emeritus before he died. May Rodriguez is the executive director.

Details about the lives of the honorees can be found in www.bantayog.org.

The ceremonies on Thursday will open at 4 p.m. at Bantayog Memorial Center on Quezon Avenue and Edsa in Quezon City.