PHOTO BY KRIXIA SUBINGSUBING

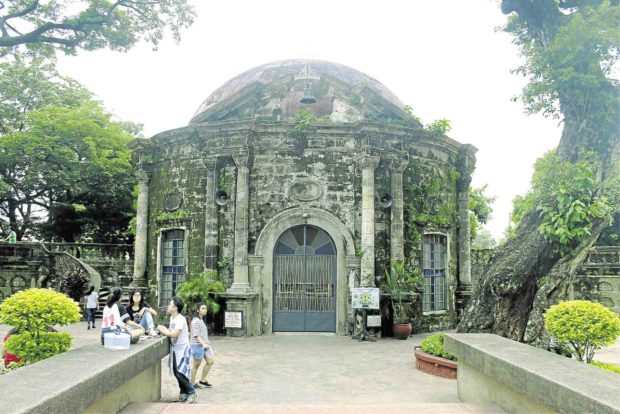

Once a final resting place for Old Manila’s rich and famous, Paco Park endures as a quiet retreat amid the urban jungle.

Now a venue for classical music concerts and weddings, its moss-covered stone walls and well-kept gardens enrich present-day gatherings with the charms of the country’s colonial past.

But in the trained eye of conservationists, Paco Park needs urgent rescuing. Those walls may evoke history, but it is feared that their strength has been compromised by layers of concrete that had buried the original material.

Those timeworn stone carvings may look good enough for Instagram, but in the right hands, their true beauty can still be resurfaced.

That challenge is currently being taken up by a group of young men and women trained by Escuela Taller de Filipinas (ET), a foundation devoted to the restoration of cultural and historic sites.

The 203-year-old Paco Park is the latest job site of the Escuela Taller crew, whose earlier restoration projects include Fort Santiago in Intramuros, Our Lady of Remedies Parish in Malate, and the old churches damaged by the 2013 earthquake in Bohol province.—GRIG C. MONTEGRANDE

The Intramuros-based organization has made capable artisans out of youths aged 18 to 25, mostly from Manila’s poorest communities. The recruits, who receive training for free, include slum residents who had dropped out of school.

“We believe preserving our heritage and solving youth unemployment go together,” says Michael Querido, the lead architect for the Paco project. “You help conserve the country’s heritage sites by employing the underprivileged. In a way, they save each other.”

Funded by the National Commission for Culture and the Arts and the Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation, ET has produced nearly 300 graduates since it was established in 2009.

ET prides itself on being the only private outfit of its kind in the country that specializes in heritage conservation. Students undergo intensive yearlong workshops in masonry, carpentry, woodworking and painting, acquiring skills that “slant toward conservation but also allow them to work regular construction jobs,” according to Philip Paraan, ET communications and special projects officer.

PHOTO BY KRIXIA SUBINGSUBING

PHOTO BY GRIG C. MONTEGRANDE

As part of its “learning by doing” methodology, students are also required to do actual conservation work for heritage sites, Paraan added.

Their projects had taken them to Fort Santiago in Intramuros; Our Lady of Remedies Church in Malate; and the old churches destroyed by the 2013 earthquake in Bohol province.

Next job

The 203-year-old Paco Park was an obvious candidate for ET’s next job. Built by Dominican priests as a municipal cemetery in 1814, it served as burial ground for Spanish aristocrats and wealthy Indios (natives) of the period.

But it also embraced patriots, like the priests Mariano Gomez, Jose Burgos and Jacinto Zamora who were executed in 1872. In December 1896, it received the remains of another martyr, Dr. Jose Rizal, keeping it in a secret, intentionally mismarked grave until the bones were exhumed in August 1898 and transferred in 1913 to the spot that would become the national hero’s monument in Luneta.

Burials at Paco Park ceased in 1912. Now under the care of the National Parks Development Committee (NPDC), it was declared a national cultural treasure by the National Museum in January 2016.

PHOTO BY KRIXIA SUBINGSUBING

In 2015, the NPDC tapped ET as technical consultant for its P12-million conservation program for the 4,100-square-meter park.

Since October this year, Escuela artisans, equipped with hammers, chisels and a keen sensitivity to things historic, have been working on the section that once served as an ossuary for infants. According to Paraan, they are providing a system or template for other NPDC contractors to follow in other areas of the park.

A tough challenge quickly presented itself when the crew examined the walls, whose original adobe structure had been covered with concrete. “It’s an unstable combination because adobe is much softer than concrete. The walls could easily collapse in a strong earthquake or even from the constant vibrations caused by trucks passing near the park,” Querido said.

Was it the fault of previous restorers? They could not easily tell. “Another problem in this field is the glaring lack of proper documentation of conservation practices and works,” Querido added.

Querido said they planned to chip away at the concrete and replace it with lime to help preserve the adobe. They would also redo the original stone carvings for the ossuary.

The process may sound simple, but it’s highly specialized work. Basic construction methods won’t do since the intent is to preserve or recreate.

“Conservation work is a never-ending process. We are always trying to find new and better ways to save our heritage sites for future generations,” Querido said.

‘Protector’ from Tondo

Christian Edward Aguirre, 25, never expected that he would become part of such an endeavor.

A high school graduate from Baseco Compound in Tondo, Aguirre used to take on different odd jobs in Divisoria, earning just about P180 a day.

He applied for a slot in the Escuela Taller program through the Department of Social Welfare and Development in 2011 and found himself enjoying the work.

He finished training in July 2012 and has since worked with ET for various restoration projects, including Fort Santiago and San Pablo Church in Laguna province.

Now the designated foreman for the Paco Park project, Aguirre looks back with pride at how this Divisoria market errand boy became a “protector” of the nation’s heritage sites.

“I’m proud of what I do here with Escuela,” Aguirre said. “I’ve been able to feed my family and at the same time feel a sense of accomplishment for having a part in something much bigger than myself.”—WITH INQUIRER RESEARCH