New and improved, they will soon be a fixture in every barangay in Quezon City, where authorities hope to gather anonymous tips or complaints on the government’s antidrug campaign.

Starting this week, bright blue fiberglass boxes will be distributed among the city’s 142 barangays under an initiative of the Quezon City Police District (QCPD).

Chief Supt. Guillermo Eleazar, the district director, said that since July 2016 each barangay had been encouraged to put up drop boxes to gather information on crime and illegal drugs from residents. But it was only this September that a “standard design” was finally agreed upon.

Earlier media reports about the project simply described it as the “Drug Box” — since its markings encouraged residents, rather bluntly, to “drop here names of suspected illegal pushers/users.”

Each barangay then was left to improvise on how its box would look like. Barangay Valencia, for example, came up with a rectangular one made of wood.

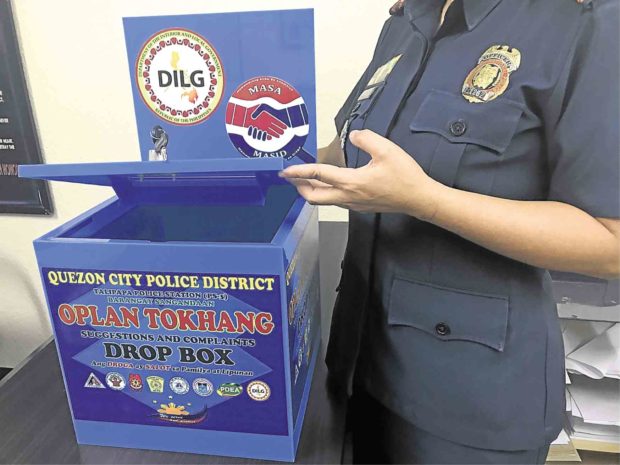

But today, the 12-cubic-inch receptacle is formally called the “Oplan Tokhang Suggestions and Complaints Drop Box.”

It sports the various logos of officialdom: the QCPD, the city government, the Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG), the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency, and the Dangerous Drugs Board.

Eleazar said the boxes are there to encourage not just tips on criminals but also complaints against his own men. He stressed that he would be open to investigate QCPD members who would commit abuses under the Duterte administration’s intensified campaign against illegal drugs.

In July, the initiative came under fire from human rights groups and other critics who feared that the crowd-sourced information on alleged drug users or pushers could be used to draw up a “hit list” for vigilante-style attacks or questionable police operations.

But Eleazar assured detractors that all information obtained through the boxes would still be validated.

“We are encouraging community participation,” he stressed in an interview on Saturday. “We need intelligence monitoring and the residents themselves know the people in their neighborhood.”

“The information gathered would only be for case buildup,” he said. “If we don’t have evidence, we cannot make an arrest.”

Just like a hotline

He pointed out that the written tips coursed through the boxes would be considered no different from those received by the PNP through its text hotline.

“There are still tipsters out there who have no cell phones. This is about giving a chance to others,” he added.

In a way, the QCPD project is serving as the model that other cities and towns are now supposed to follow. It was implemented ahead of a recent DILG order for local government units nationwide to have similar initiatives under a program dubbed “Masa Masid” (or Mamamayang Ayaw sa Anomalya, Mamamayang Ayaw sa Droga).

A DILG memorandum issued in August, which revised the guidelines for Masa Masid, called for the setup of drop boxes as a means for citizens to report crime, illegal drugs, corruption and other threats to peace and security.

4 p.m. Thursday habit?

The memo even prescribed the proper procedures when opening a box and examining the contents. At least six members of a technical working committee should be present to witness it.

In Quezon City, the proposal is to open the boxes at 4 p.m. every Thursday, the Inquirer learned.

A police officer, who holds the key to the box as the designated “focal person” in a barangay, will unlock it in the presence of barangay officials and representatives from the Barangay Anti-Drug Abuse and Advisory Council (BADAC), the Liga ng mga Barangay, faith-based organizations, and civil society groups.

The representatives would also be in charge of monitoring the reporting system, as well as the segregation and assessment of information and its referral to concerned government agencies, including the PNP and the Office of the Ombudsman.

Eleazar said the boxes would be supplied by the QCPD. The barangays may place their orders at P2,000 per box, the money drawn from their BADAC funds.

The National Union of Peoples’ Lawyers (NUPL), however, continued to warn against the project as a “dangerous shortcut” in the fight against drugs and crime.

NUPL president Edre Olalia said having such boxes would have a chilling effect in communities where the police as “Big Brother” would be spawning “many Little Brothers” among the neighbors.

Intrigue, suspicion

“It would only stoke intrigue and suspicion among residents,” he said in an interview. “Instead of unifying the people against the drug problem in a legal, scientific and holistic way, you divide and polarize them.”

“I don’t see it as justifiable, particularly within the framework of the drug war,” said Olalia, adding that he had never seen anything like it done in other countries.

The QCPD should instead stick to “good, old-fashioned police work that is scientific, systematic and credible” in building cases, the lawyer stressed.

“The state has all the resources, whether human or material resources, to conduct credible and reliable police work to pursue investigation and intelligence without crossing over the line of human rights violations,” he said.