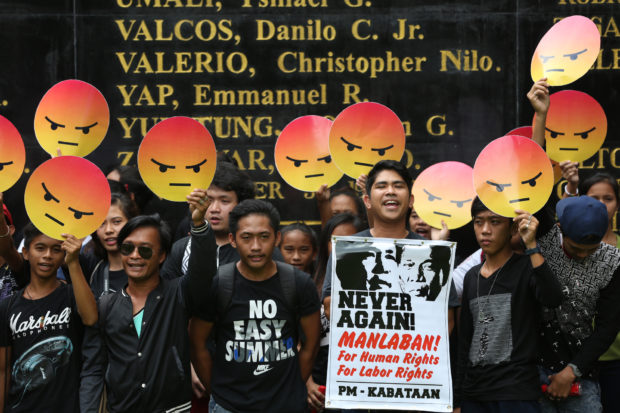

ANGRY MILLENNIALS Young activists and survivors of Ferdinand Marcos’ martial rule display angry emoticons during the “Encounter between Millennials and Martial Law Survivors” at Bantayog ng mga Bayani to mark the 45th anniversary of the late dictator’s declaration. —NIÑO JESUS ORBETA

(Last of a series)

For the government agency responsible for the gargantuan task of reviewing thousands upon thousands of haunting stories of human rights violations under the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos, its biggest challenge may yet be its race against time.

With its mandate lapsing on May 12, 2018, the clock is ticking fast for the Human Rights Victims’ Claims Board (HRVCB), which is in charge of documenting accounts of illegal detention, torture, killings, and disappearances during the Marcos regime and compensating the victims.

HRVCB Chair Lina Sarmiento, however, is undaunted.

“Not finishing the task is not in our vocabulary,” the former police general said in an interview with the Inquirer. “Not meeting the deadline is something the board does not see itself in because we already committed to this—even if it means sleepless nights.”

2-year extension

Republic Act No. 10368, or the Human Rights Victims Reparation and Recognition Act passed in 2013, created the board in 2014 and directed it to complete its task by May 2016. That period was extended by two years by RA 10766 that was approved last year.

The HRVCB has received 75,730 claims backed by voluminous documents that detailed alleged abuses committed against opponents of the dictatorship as well as ordinary people victimized by the Marcos regime.

In May, the board released an initial list of 4,000 eligible claimants, mostly from Metro Manila, the Davao region and Western Visayas. About 3,700 have received partial compensation.

Validating claims

Before the nation marked the 45th anniversary of the declaration of martial law this week, Sarmiento said the board had already decided on 57,846 claims, but she could not immediately say how many it found valid.

“We are really rushing … so that we can finish writing all our decisions by the end of the year,” she said. “We cannot change the target anymore because we have no more time, no more elbow room.”

The HRVCB is divided into three divisions that decide on the claims. With three board members and a handful of young paralegals, each division handles more than 25,000 cases of alleged atrocities committed by state forces from Sept. 21, 1972, to Feb. 25, 1986.

“It’s very difficult. I wish there was an easier way, but you have to examine each and every document, counterchecking it with other claims and other references available,” Sarmiento said.

Going through the raw and harrowing accounts of the martial law victims from all over the country have taken an emotional toll on some of the paralegals who were too young to remember or were not even born yet during that period, according to lawyer and board member Byron Bocar.

Reparation law

The reparation law provides a point system to determine the amount of compensation for each victim.

Those who died or had disappeared and still missing would receive the maximum 10 points. Victims of torture, rape or sexual abuse are given five to nine points each and those detained get three to five points.

“Ours is an evidence-based adjudication. So the burden of proof is really on the claimant,” said Sarmiento, who once headed the Directorate of Police Community Relations of the Philippine National Police.

The law provided P10 billion for the compensation, which would be taken from the ill-gotten wealth of the Marcos family, specifically their Swiss deposits, which amounted to $683 million in 2004 and forfeited in favor of the government.

The final value of each point could only be established once the HRVCB finally decides on all 75,730 claims. Each point was initially pegged at P25,000, but recently approved claimants were to receive only half of this amount for now.

Struggle for recognition

Beyond the monetary awards, however, the bigger struggle for the survivors is the recognition of their suffering at the hands of martial law authorities.

Writer Bonifacio Ilagan, who was severely tortured and detained for two years when he was a student activist, said the return of the Marcos family to power was a big insult that heightened the “indescribable” pain from his and his family’s ordeal.

“For the longest time, [recognition] has been denied, and not one whom we accused of violations of human rights had been formally charged,” he told the Inquirer.

Now in his 60s, the torture he was subjected to is still vivid to “Ka Boni,” who untiringly retells his harrowing experiences to young people in hopes of opening the eyes of the post-martial law generations to the truth about that dark period.

Beyond his physical torture, he continues to feel the gnawing pain of losing his younger sister, Rizalina, also an activist who was abducted in 1977 and remains missing to this day. She was one of the “Southern Tagalog 10,” the biggest single group that disappeared during the martial law period and never heard from again.

“Legislation is a small step. The greater part is that those who were responsible for the dictatorship should be brought to justice,” said Ilagan, who is vice chair of Samahan ng mga Ex-Detainees Laban sa Detensyon at Aresto.

Noncash benefits

The law also provides nonmonetary benefits to the victims and their families. These include social services from the Department of Health (DOH), the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD), the Department of Education, the Commission on Higher Education and the Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (Tesda).

Sarmiento said the HRVCB has been in talks with these government agencies and agreements have been reached with DOH, DSWD and Tesda.

Despite the looming deadline, she said she remained optimistic about accomplishing their task, and later, turning over all their documents to the Human Rights Violations Victim’s Memorial Commission.

Tangible contribution

The commission would be created for the “establishment, restoration and conservation” of a memorial, museum, library or compendium in honor of the victims of human rights violations under Marcos.

“By May 12, 2018, we will cease to exist,” she said. “But our tangible contribution, as provided by the law, is the Roll of Human Rights Violations Victims.”

The roll ensures that the victims are given due recognition for the suffering and their heroism during the dictatorship.

For Ilagan and the thousands of other victims and survivors of the Marcos dictatorship, this recognition is but a silver lining to the fight that would continue beyond the HRVCB’s lifespan.

“[Our names] will never be erased from the records, from our history,” he said. “We may be old now, but we can keep sharing the stories of our youth to the youth of today.”