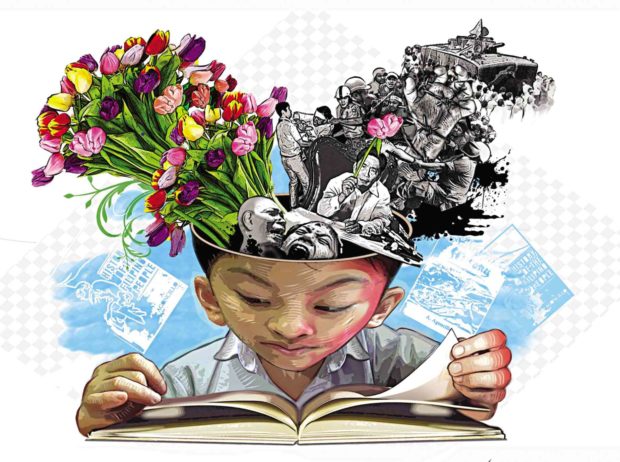

‘Kuri-kulam’: Are textbooks sanitizing martial law?

ILLUSTRATION BY RENE ELEVERA

Today’s youth know very little about the dark years of martial law under the Marcos dictatorship. And who can blame them? The K to 12 Basic Education Curriculum and the textbooks used under it seem to exhibit selective amnesia when it comes to the horrors that visited the country from the onset of martial law in 1972, to the popular ouster of its author in 1986.

The result: The dictator’s son, Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. almost clinched the vice presidency in the 2016 election because the bulk of his supporters were millennials with little or no sense of history whatsoever.

Simply put, Philippine history has become obsolete, as far as high school textbooks are concerned. It’s been excluded from the Araling Panlipunan (Social Studies) high school curriculum. Asian History is tackled in Grade 7, World History in Grade 8, Economics in Grade 9, and Contemporary Issues in Grade 10. Where is Philippine History in the curriculum?

The teaching of Philippine History has become part of the Grade 6 subject Hekasi (Geography, History and Civics). Being only a third of a one-year course and being merely introductory in nature, Philippine History — particularly the discussion on Marcos and martial law — is often glossed over, even trivialized.

Take the Grade 6 public school textbook titled “Pilipinas: Bansang Papaunlad.” In Chapter 8, it begins its discussion of “The Struggles for Independence,” starting with the Propaganda Movement.

Article continues after this advertisementThe chapter, however, ends with “The Return of the Philippine Commonwealth,” as if Philippine History stopped right there and with the country’s Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1946. Nothing more is said about Philippine History, Marcos or martial law.

Article continues after this advertisementInnocuous passages

The textbook “Lahing Kayumanggi” meanwhile discusses martial law in three innocuous and generic passages: “During Marcos’ tenure, many problems and troubles happened in the country. Marcos used this as a pretext to declare martial law. Because of this, many human rights were trampled upon.”

The bulk of the 18 pages of Lesson 14 (“Ang Batas Militar”) in the textbook “Isang Bansa, Isang Lahi” is devoted to a listing of the positive effects of the dictatorship. “Under martial law, Marcos initiated reforms in seven areas—peace and order, land reform, livelihood programs, inculcation of moral values through education, government reorganization, employment, and social services.” Only two and a half pages are used to discuss the negative aspects of martial law.

Similarly, only three lines pertaining to Marcos and martial law are found in the textbook “Philippines, Our Philippines.” The lines read: “An example of a dictatorship is the Philippines during the Martial Rule of Marcos. The provisions of the 1973 Constitution were not implemented because Marcos had placed the country under martial law. He changed the structure of government to strengthen the powers of the president.”

Meanwhile, “Worktext in Geography, History and Civics” does not discuss Philippine History at all!

“Ang Bayan Kong Pilipinas” also glosses over Philippine History. In Lesson 2 of Unit 3, the narration of the entire history of the Philippines from pre-colonial times to the present is compressed into nine pages. As for martial law, this is how the book discusses it: “By virtue of Presidential Decree No. 1081, Marcos declared martial law all over the country in 1972. He formed a new Constitution which established a new form of government where he was both President and Prime Minister. Under martial law, many rights of the citizens were taken away. Marcos jailed his political enemies.” That’s it.

Philippine Independence

“Pilipinas: Ating Bayang Sinilangan” begins its narration on Philippine History with the arrival of Magellan in 1521, and ends with the Declaration of Philippine Independence on July 4, 1946. Just as if the Philippines had ceased to exist after that!

Lesson 13 of the Grade 6 textbook “Kultura, Kasaysayan at Kabuhayan” begins with the Three Martyr Priests (Gomburza), and ends with the grant of Philippine Independence by the United States on July 4, 1946. It gives a three-paragraph description of the 21-year Marcos rule, extolling his supposed virtues without saying anything about the evils that martial law had perpetrated.

One won’t find anything on Philippine History either in “Kayamanan.” The name Marcos appears but once in this passage: “An example of a dictatorship is the Philippines when it was under the martial rule of former President Ferdinand Marcos.”

“Ang Lahing Pilipino, Dakila at Marangal” most dispassionately recounts the establishment of the Fourth Republic under Marcos, stating it in just one sentence: “Before he finished his second term as President, Marcos declared martial law on Sept. 21, 1972.” That was all.

Concerted reluctance

This pattern of collective and concerted reluctance and, in some cases, outright refusal by local textbook authors and publishers to acknowledge and include in their textbooks the truth about martial law under Marcos bodes ill for the country. Twisting or withholding information as vital as this is disinformation and misinformation of the worst kind, the kind of propaganda that thrives on subterfuge and deceit, whitewashing the mistakes of the past by not showing them at all.

So what becomes the students’ basis for comparison? To whom will they turn to for guidance and direction when nothing is presented and explained to them? A “kuri-kulam” (from the Tagalog word “kulam” or “black magic”) then emerges that totally does away with its duty of explaining Philippine History, Marcos and martial law, to high school students. A curriculum determined to sanitize evil by skirting, trivializing and ignoring this dark era creates a frightening scenario akin to a total news blackout, the kind that invites witches, warlocks and trolls into the innermost sanctum of our children’s minds.

Witches’ brew

The many infirmities and defects cited are the potent ingredients that comprise the witches’ brew that is the K to 12 curriculum. Forced to ingest this dubious concoction of hidden, withheld, sanitized or falsified information, the students are kept under a spell, mesmerized into believing the lie that Marcos was benevolent, that martial law was absolutely necessary. The evil in the K to 12 curriculum must be exorcized. Deceitful and duplicitous textbooks such as those cited ought to be burned at the stake like the witches and warlocks that they are.

How can you love something when you know nothing about it? To teach children love of country, nationalism and patriotism, they must be told about the long and arduous journey our forefathers took to get us to where we are.

The K to 12 social studies curriculum should be restructured to conform to this imperative. National Identity should be taught in Grade 1, Customs and Traditions in Grade 2, Civics and Citizenship in Grade 3, Philippine Geography in Grade 4, World Geography in Grade 5, Philippine History from Prehistory to the Spanish Colonization in Grade 6, Philippine History from the Philippine Revolution to the Present in Grade 7, The Constitution and the Three Branches of Government in Grade 8, the History of Asia in Grade 9, History of the World in Grade 10, Economics in Grade 11, and Contemporary Issues in Grade 12.